Saban: Current state of college football not ‘sustainable’

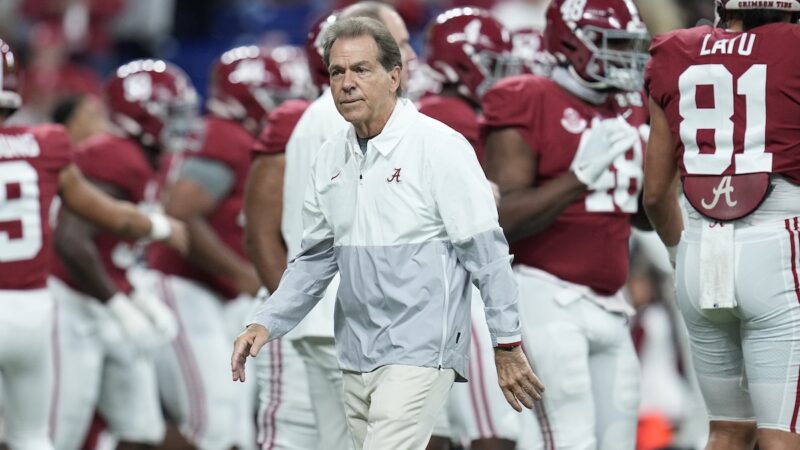

Alabama head coach Nick Saban watches warm ups before the College Football Playoff championship football game against Georgia Monday, Jan. 10, 2022, in Indianapolis.

By RALPH D. RUSSO, AP College Football Writer

TUSCALOOSA, Ala. (AP) — Nick Saban’s willingness to adapt and often be a catalyst for change in college football, both on the field and off, has propelled Alabama to six national championships in 13 seasons.

The 70-year-old coach is confident his program will continue to thrive during this new era of college athletics, with players having more opportunities to earn money than ever before and more power to determine where they play.

But the current state of college football has Saban concerned.

“I don’t think what we’re doing right now is a sustainable model,” Saban told The Associated Press in a recent interview.

That’s a common theme among coaches these days, with Clemson’s Dabo Swinney and Southern California’s Lincoln Riley among the most prominent who have echoed Saban’s sentiments. The combination of empowered athletes and easily accessible paydays is changing the way coaches go about their business.

The uncertainty comes with the NCAA in a weakened state following last year’s Supreme Court loss and in the midst of a dramatic restructuring. Schools and the NCAA itself would prefer federal legislation to regulate how athletes are compensated for their names, images and likenesses, but when that might come and in what form is unknown.

That has led to concerns about vast sums of money flowing in and around college athletics, including brazen entities called collectives put together by well-heeled donors whose donations have traditionally funded everything from lavish facilities to multimillion-dollar buyouts of fired coaches around Power Five conferences.

“The concept of name, image and likeness was for players to be able to use their name, image and likeness to create opportunities for themselves. That’s what it was,” Saban said. “So last year on our team, our guys probably made as much or more than anybody in the country.”

Paying a player to attend a particular school is still a violation of NCAA rules, but NIL deals have quickly become intertwined with recruiting — both high school prospects and the growing number of college transfers.

“But that creates a situation where you can basically buy players,” Saban said. “You can do it in recruiting. I mean, if that’s what we want college football to be, I don’t know. And you can also get players to get in the transfer portal to see if they can get more someplace else than they can get at your place.”

Riley told reporters last week NIL has “completely changed” recruiting.

“I think that anybody that cares about college football is not real pleased with that because that wasn’t the intention,” said Riley, who is in his first season at Southern California after five years at Oklahoma. “And I’m sure, at some point, there is going to be a market correction if you will, with recruiting.”

What exactly is going on with recruiting and NIL is hard to know for sure because it is mostly happening outside the purview of schools and the NCAA between parties with no obligation to publicly disclose deals.

A NIL contract drawn up for an unidentified blue-chip recruit reportedly could be worth up to $8 million. Earlier this year, Texas A&M coach Jimbo Fisher was angered by rumors the Aggies used millions in NIL money to sign the nation’s consensus No. 1 recruiting class for 2022.

Mississippi coach Lane Kiffin is among those who worry about conflicts in recruiting between coaches and emboldened boosters,

“I think that there’s going to start being issues potentially of donors and collective groups saying they want Player A from their area. And the coaching staff wants Player B,” Kiffin told AP.

Swinney told ESPN major college football needs a “complete blowup” that might result in something that looks more like professional football.

“I think you’ll have 40 or 50 teams and a commissioner and here are the rules,” he said.

Saban said he is not against the shift toward players being compensated and given more freedom to switch teams.

“We now have an NFL model with no contracts, but everybody has free agency,” said Saban, echoing a comparison Kiffin has made.

“It’s fine for players to get money. I’m all for that. I’m not against that. But there also has to be some responsibility on both ends, which you could call a contract. So that you have an opportunity to develop people in a way that’s going to help them be successful,” Saban said.

Saban, the highest-paid coach in college football with a salary of nearly $10 million last season, said the balance of power in the sport could tip toward the schools with the wealthiest collectives.

“So there’s going to have to be some changes implemented, some kind of way to still create a level playing field,” he said. “And there is no salary cap. So whatever school decides they want to pay the most, they have the best chance to have the best team. And that’s never been college football, either.”

Saban would prefer Alabama guarantee a set amount of money for every player who plays football for the Crimson Tide.

“We give everybody the same medical care, academic support, food service. Same scholarship. So if we’re going to do this, then everybody is going to benefit equally. I’m not going to create a caste system on our team,” Saban said.

LSU coach Brian Kelly supports a similar model, with players agreeing to sign over certain NIL rights for a base amount of compensation along with the ability for a school to help boost an individual’s brand.

“And we’ve got the best NFT, “ Kelly added, referring to the popular digital collectors’ items. ”Who can’t sell Mike the Tiger?”

Saban isn’t worried about the changing landscape derailing his dynasty. Alabama had more players on NFL rosters (53) than any school at the beginning of last season. The Tide’s track record of personal and professional development should remain attractive to top players, though maybe not quite as many as in the past.

Saban is OK with that.

“I know we have to adapt to that,” Saban said. “You’re going to have kids out there that say, ‘Well, I can get a better deal going someplace else,’ and they’ll go there. But you’re also going to have people that see the light and say, ‘Yeah, they’ve got a good history of developing players. They got a good history of developing people, they got a great graduation rate and that value is more important.’

“And they’re distributing money to everybody in the organization.”

‘One year of failure.’ The Lancet slams RFK Jr.’s first year as health chief

In a scathing review, the top US medical journal's editorial board warned that the "destruction that Kennedy has wrought in 1 in office might take generations to repair."

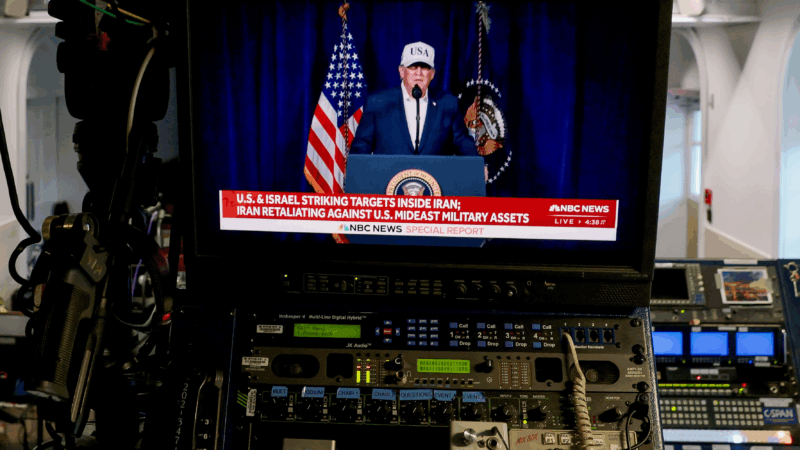

Here’s how world leaders are reacting to the US-Israel strikes on Iran

Several leaders voiced support for the operation – but most, including those who stopped short of condemning it, called for restraint moving forward.

How could the U.S. strikes in Iran affect the world’s oil supply?

Despite sanctions, Iran is one of the world's major oil producers, with much of its crude exported to China.

Why is the U.S. attacking Iran? Six things to know

The U.S. and Israel launched military strikes in Iran, targeting Khamenei and the Iranian president. "Operation Epic Fury" will be "massive and ongoing," President Trump said Saturday morning.

Sen. Tim Kaine calls on the Senate to vote on the war powers resolution

NPR's Scott Simon talks to Sen. Tim Kaine, D-Va., about the U.S. strikes on Iran.

Iran strikes were launched without approval from Congress, deeply dividing lawmakers

Top lawmakers were notified about the operation shortly before it was launched, but the White House did not seek authorization from Congress to carry out the strikes.