Local Group Effort Seeks to Overcome Barriers of Legal Status, Language to Offer COVID-19 Testing

By Hank Black, BirminghamWatch

In what one health researcher called an “amazing group effort” during the coronavirus crisis, several organizations have come together to devise a unified strategy to reach Latino and other non-English-speaking residents of Jefferson County with information and support.

The need was evident – in a pandemic, all sectors of society are at risk of being infected and of infecting others. But the Latino community carries additional burdens. They have high risks of pre-existing conditions, including the nation’s highest incidence of diabetes, placing them at greater risk of dying from COVID-19. Almost 85% of Latinos have Zoom-proof jobs and cannot work from home – and they work on the front lines of the viral threat in jobs predominately classified as “essential” in hospitals, nursing homes, restaurants, construction and public works. To compound things, they are least likely of all major demographic groups to have health insurance.

According to The Migration Policy Institute, six million immigrants work in frontline occupations such as health care, food production and transportation. They are overrepresented in certain critical occupations, such as doctors and home health aides, where they face heightened risk of exposure. Another 6 million immigrants work in industries such as food services and domestic household services that have been economically devastated, making up 20% of the total workers in those industries.

The two main impediments to educating immigrants about testing and treatment for the virus are the inability to speak and read English, and the omnipresent fear of being detained and deported because many do not have legal status to be in this country, according to Carlos Aleman, deputy director the Hispanic Interest Coalition of Alabama, known as HICA.

“And that’s in addition to the institutional barriers that always exist, such as lack of transportation,” Aleman said.

As recently as mid-March, he added, it was unclear whether undocumented people could receive testing and whether, under the Trump Administration’s “public charge” rule, even those in the country legally could receive access to care.

The rule holds that if an applicant claims one or more public benefits for a period greater than a year, they become a “public charge” and can be denied visa extensions or a green card. On March 17, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services said immigrants who undergo medical testing for the coronavirus or treatment related to it will not be penalized when applying for green cards and visas under the newly enacted public charge rule.

Data from COVID-19 hotspots such as New York City and San Francisco revealed that Latinos were overrepresented in death totals, putting local officials on alert. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently noted that 16.5% of U.S. COVID-19 deaths are among Latinos, and the U.S. population is 18.3% Latino. However, when CDC used weighted population distributions, the Latino death rate became 26.9%.

“The weighted population distributions ensure that the population estimates and percentages of COVID-19 deaths represent comparable geographic areas in order to provide information about whether certain racial and ethnic subgroups are experiencing a disproportionate burden of mortality,” the CDC wrote.

That extreme disparity has not shown up in many other parts of the country, including in Alabama, where Latinos make up 4.4% of the state’s total population. Data on Latino rates of infection and death are not known for Alabama.

“They are a smaller percentage of the population here, and we’re just now getting to them in a concerted effort,” according to Isabel Scarinci, a UAB researcher in health disparities.

Outreach to Latinos

Aleman said an all-out, targeted campaign has begun to reach the Latino community with Spanish language education and promotion of pandemic guidelines, testing sites, and a dedicated phone line for pre-test screening and appointments. That number is 205-975-2819.

Local Latino-oriented radio is used heavily to communicate with the community, Aleman and others said. Information also is placed in the two local Spanish-language newspapers. Social media is integral to the effort, such as Facebook and WhatsApp.

In addition, on-the-ground advertising of testing sites and other information is accomplished with flyers that blanket area ethnic markets, churches and retail stores.

The establishment of a unified command structure under the aegis of Jefferson County has helped coordinate and amplify COVID-19 messaging. The effort brings together the Jefferson County Commission, Health Department and Emergency Management Agency; UAB; cities of Birmingham and Hoover; Birmingham Airport Authority; Birmingham Housing Authority; and others.

The unified command is helping UAB coordinate a growing number of community-based COVID-19, drive-through test sites, including Central Park, Center Point and East Lake, in hopes of reaching more African-American and Latino communities. Testing there provides more convenient alternatives to the central UAB location at University Boulevard and 22nd Street South. Screening through the dedicated telephone line is required before testing appointments can be given. The Jefferson County Department of Health is covering the cost of testing for residents of the county who do not have health insurance.

“Not everyone wants to or can come to a downtown drive-through testing site, so we wanted to meet (them) in their communities,” UAB vice president for clinical operations Jordan DeMoss said recently. “Our goal is to identify those residents who do not speak English and need interpretation – really any language – and provide on-site interpreters for those who need it.”

DeMoss said partnerships leveraged through the unified command center as well as those established through the UAB Minority Health and Health Disparities Research Center have made possible the mobile testing units that serve neighborhood locations.

Adriana Valenzuela, public health language coordinator for the health department, is part of a “special population” team that helps develop strategies to target people with limited English proficiency. It is predominately oriented toward Spanish-speakers, but it also includes those who speak indigenous languages of the Americas as well as Asian languages.

Valenzuela said, “The question of trust has been addressed from the very beginning. We conveyed through all our partners that, with COVID-19, it doesn’t matter if you are illegal or undocumented. This is a public health threat and affects us all. Our team is encouraged to be proactive about contacting residents and assuring them it’s safe.”

She said accurate and uniform information that induces trust is now reaching Spanish-speaking residents through the Jefferson County Open Data pages.

Updates on testing sites and other information is also available by texting BHMCOVID19 to 888-777.

Aleman said trust is key when reaching out to communities that historically have been marginalized. “We are at a point in time where the immigrant community has a lot of concern with how the government perceives them,” he said. “You have the president talking about shutting down all immigration, and undocumented immigration in particular, so that’s a huge barrier in terms of establishing trust between institutions and people.”

He said poverty is another barrier to overcome in order to effectively confront the pandemic. A lack of money is an impediment to finding and affording basic, virus-fighting products such as gloves, masks and disinfectant wipes.

The impact of poverty was highlighted in a Washington Post-Ipsos poll published May 7. It revealed that Latinos are “nearly twice as likely as whites to have lost their jobs amid the coronavirus shutdowns.”

A recent survey from The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research turned up similar results. It found that 61% of Latinos have experienced household income loss, including job losses, unpaid leave, pay cuts and fewer scheduled hours, compared with 46% of Americans overall.

Groups Coordinate

UAB’s Scarinci, who has worked for years to reduce disparities in cancer outcomes in African American and Latino populations, became a linchpin in the shift to dealing with the coronavirus pandemic. “This is really an amazing group effort. It’s wonderful in how this engaged so many partners and got organized in a short time,” Scarinci said.

Resources of the Hispanic Interest Coalition of Alabama and of AIDS Alabama have been vital to getting a targeted testing program underway. Physicians, social workers and others from UAB and the health department came on board with the effort. They enlisted others, including clinics such as the nonprofit Christ Health Center in Avondale, that treat underserved populations.

UAB and the Christ Health Center are among those committed to providing treatment to anyone who tests positive for COVID-19, even if they do not have health insurance. “It would be unethical to do this screening if we could not shepherd these individuals through their care,” Scarinci said.

AIDS Alabama has a long history of working in Latino communities in Jefferson and surrounding counties.

“We are trying to have a net of resources where people can talk and have information in Spanish – have interpreters at the testing sites, make sure we have Spanish-speakers on the phone lines who can tell you exactly what is going on, what happens if you test positive, and to give more instruction if you are to test positive and live with other people,” said Jean Hernandez, who coordinates that outreach program.

Hernandez knows people who lost several friends and family to HIV/AIDS, and she fears the same will be true for COVID-19. “We want people to have the proper equipment and tools for good information and know where to go for treatment,” she said. “Launching this network of medical providers and community workers and free testing lets people know what is going on, and once it is underway and we are in the communities, we can reach even more people.”

Chicagoans pay respects to Jesse Jackson as cross-country memorial services begin

Memorial services for the Rev. Jesse Jackson Sr. to honor his long civil rights legacy begin in Chicago. Events will also take place in Washington, D.C., and South Carolina, where he was born and began his activism.

In reversal, Warner Bros. jilts Netflix for Paramount

Warner Bros. says Paramount's sweetened bid to buy the whole company is "superior" to an $83 billion deal it struck with Netflix for just its streaming services, studios, and intellectual property.

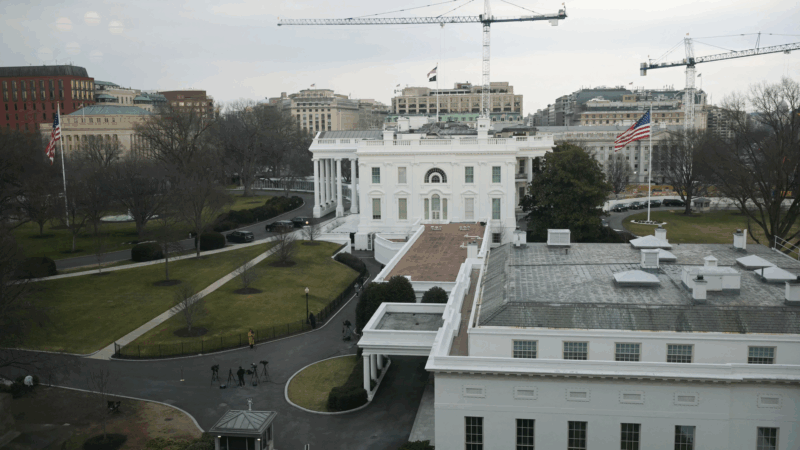

Trump’s ballroom project can continue for now, court says

A US District Judge denied a preservation group's effort to put a pause on construction

NASA lost a lunar spacecraft one day after launch. A new report details what went wrong

Why did a $72 million mission to study water on the moon fail so soon after launch? A new NASA report has the answer.

Columbia student detained by ICE is abruptly released after Mamdani meets with Trump

Hours after the student was taken into custody in her campus apartment, she was released, after New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani expressed concerns about the arrest to President Trump.

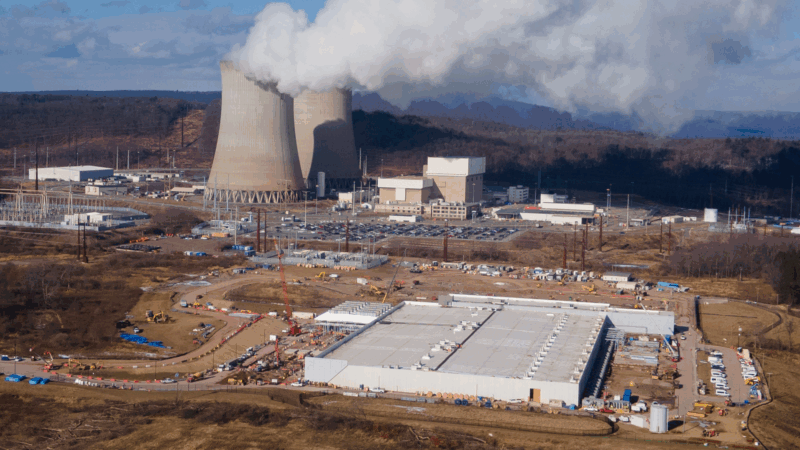

These major issues have brought together Democrats and Republicans in states

Across the country, Republicans and Democrats have found bipartisan agreement on regulating artificial intelligence and data centers. But it's not just big tech aligning the two parties.