Alabama Struggling With Racial Disparities In Child Poverty Levels, Report Says

Even as Alabama’s child population grows more diverse, children of color are experiencing disproportionately high rates of poverty, according to a report published Thursday using pre-pandemic data.

The report, titled Alabama Kids Count, indicates that children of color will make up the majority of the child population and the majority of the workforce by 2030. At the same time, Black and Hispanic children suffered average poverty rates of 41.9% and 42.6%, respectively, between 2014 and 2018. The rate for white children was 16.5%.

These findings are especially significant considering that Alabama’s child population is shrinking, said Stephen Woerner, the executive director of Voices for Alabama’s Children, which has published the Alabama Kids Count report annually since 1994. Though Alabama’s overall population grew by 10% from 2000 to 2019, its child population shrank by 3%.

“Minority children are more likely to struggle in school. Minority children are more likely to live in poverty. And so as the workforce ages, we need these kids to be successful to be the next generation of workers,” Woerner said.

High poverty levels also are associated with a gap in educational achievement, according to the report. For example, fourth and eighth-graders who live in poverty had reading and math proficiency rates that were 26 to 29 percentage points lower than students who were in households above the poverty line.

Both Alabama’s overall poverty rate and its childhood poverty rate have increased over the past decade. From 2014 to 2018, the average rate of children living in poverty was 25.1%, up from 21.5% in 2000.

Racial disparities also exist in schools. The report found that, for the 2018-2019 school year, black students were suspended at a rate of 19%. All other races had a rate of 9.9% or less.

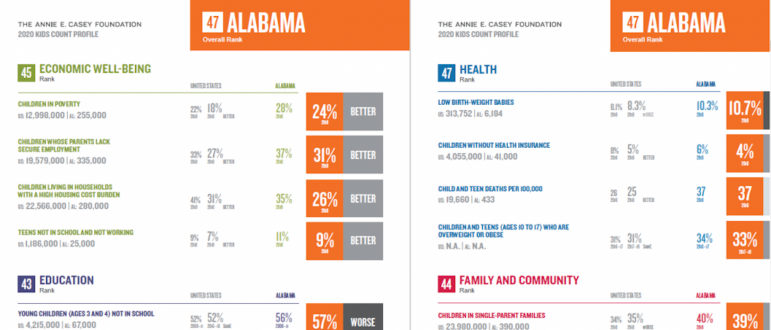

Still, Alabama has shown some areas of improvement when it comes to the well-being of its children. Infant mortality in 2018 was 7.0 per 1,000 live births, down from 9.5 in 2008. Similarly, teen pregnancy rates decreased by nearly half from 2008 to 2018.

And in the 2020-2021 school year, 38.2% of 4-year-olds participated in the state’s First Class Pre-K Program, which meets or exceeds all 10 of the benchmarks set out by the National Institute for Early Education Research.

In fact, among 16 key indicators divided equally among the categories of family and community, economic well-being, education and health, Alabama showed improvement in 11 of them. It did worse in just two of those indicators.

Yet Alabama is still ranked 47th in the nation in overall child well-being, ahead of Louisiana, Mississippi and New Mexico. Woerner said the ranking shows that, while Alabama is making headway in improving some conditions for its children, it is not improving as quickly as other states.

“We’ve got to continue at the legislative level, the agency level to prioritize those decisions that impact kids,” Woerner said. “Because if we don’t, we’re going to continue to fall back even though compared to ourselves, we continue to improve.”

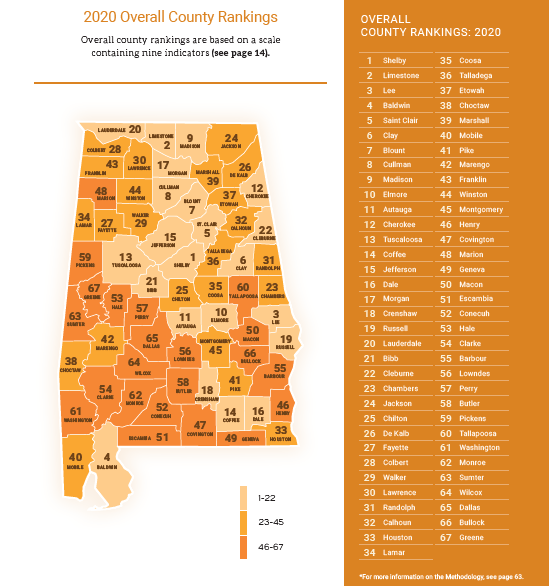

At the county level, Shelby County was ranked first in child well-being based on nine indicators split among health, education, safety and economic security. Jefferson County was ranked 15, and Greene County came in last at 67.

Even Worse Conditions Projected Under COVID

Much of the report compares data from 2008 to data from 2018 and 2019. As a result, the report warns that “virtually none” of the data used reflects current circumstances.

Woerner said he expects the pandemic — and all of the challenges it has brought — will affect almost every single indicator his group studies. Because it takes time for the state to collect and report data, the final impact of the pandemic on Alabama’s children may not be known for years.

There already are signs that the pandemic may have made things worse, according to Woerner. He pointed to rates of child abuse and neglect as an example.

According to the report, rates of abuse already had increased to 11.1 children per 1,000 in FY 2019 compared to 5.1 per 1,000 in 2008. Woerner said those numbers likely will go up because the pandemic has created high-stress environments for families, which can in turn lead to more abuse.

“There’s so much stress, unprecedented stress on families. They’re all living under the same roof, there’s no school to go to, mom and dad are unemployed,” Woerner said. “We’ve been told anecdotally throughout all of the pandemic that reported cases of child abuse were going down. But then what they were getting was kids ending up in the hospital.”

Though the pandemic will likely cause significant changes in the indicators studied, the report states that its findings will serve as a baseline that future researchers can use to more fully understand the pandemic’s impact on children.

“What readers should take away from this approach is the pandemic did not cause the inequities in child well-being but it exposed cracks hiding in our system,” the report reads. “The 2020 Alabama Kids Count Data Book clearly shows many of these disparities have existed for years.”

Mundane, magic, maybe both — a new book explores ‘The Writer’s Room’

Why are we captivated by the spaces where where authors write? Katie da Cunha Lewin set out to explore "The Hidden Worlds That Shape the Books We Love."

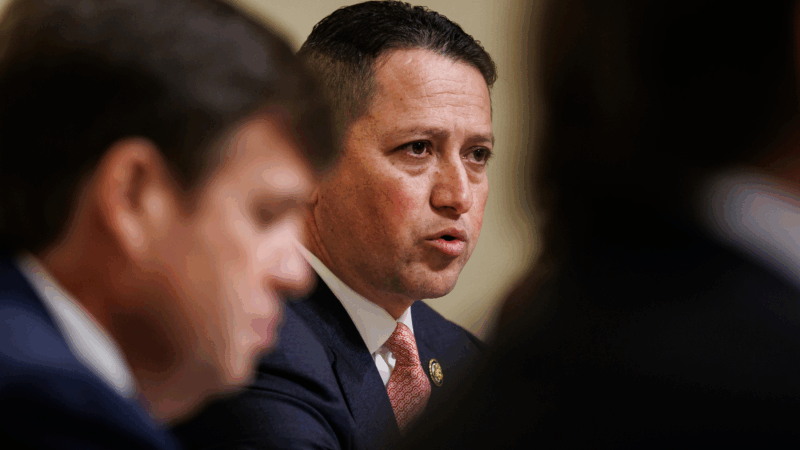

GOP Rep. Tony Gonzales heads to a runoff in Texas amid a new ethics probe in the House

Texas Republican Rep. Tony Gonzales has faced increasing pressure from his party to resign or drop out of his race after allegations of an affair with a staffer.

Satellite images show Iran school strike hit more targets than earlier reported

The images suggest that precision munitions struck other buildings, including a clinic that was also inside the complex.

As live music becomes more inaccessible, most fans stay watching through screens

Now that it is becoming harder and harder to get a ticket to your favorite artist's show, watching indirectly is becoming a popular compromise. What is gained and lost in a tiered concert hierarchy?

Paul McCartney’s decade of transformation: From Beatles breakup to John Lennon’s murder

Man on the Run shows McCartney's effort to define himself outside The Beatles' shadow: "Paul making this documentary was a way of coming to terms with that whole period," says director Morgan Neville.

A Biden-era rule sought to stabilize child care. Why Trump wants it gone

The Trump administration has proposed repealing a Biden-era rule that required states to change how they pay out child care subsidies, citing the potential for fraud.