The Mighty Wurlitzer Returns to its Roots at Sidewalk

Visit the Alabama Theatre in downtown Birmingham, face the stage and you might notice the red and gold console to the left. It’s a theatre organ known as the Mighty Wurlitzer. It’s an instrument whose heyday has long past. But this weekend, as part of the Sidewalk Film Festival, it’ll return to its original purpose: accompanying silent films.

First, a little history

Before films had sound, theater owners used live music for accompaniment. Wurlitzer, one of a number of piano manufacturers, smelled an opportunity.

“They went to theaters, theater management, the studios and said ‘Why would you want to pay a 42-piece orchestra to play every night when, if you purchased one of our instruments, you could put it in, install it and have one person?’” Alabama Theatre house organist Gary Jones says. “’Think of the payroll savings you would have.’ And that was their marketing tactic and it worked.”

Since the theatre organ would replace an orchestra, it was designed to mimic one. Wurlitzer actually called its product a “unit orchestra.” It can produce an array of sounds such as strings, trumpets, trombones, clarinet, oboe or flute. In addition to the pipes are percussion instruments from drums to symbols to chimes to glockenspiel.

Perhaps the most fun feature of the organ is its sound effects. The Alabama Theatre’s collection includes a train whistle, a Klaxon horn (that old-timey “awooga” car horn) and horse hooves, which, in true Monty Python tradition, are two wooden shells clapped together. They’re sounds that can accent what’s on screen.

It’s a Rube Goldberg-like machine driven by air and electricity. It’s all mechanical with no electronically-generated sound.

The Alabama Theatre installed its Wurlitzer in 1927 when the venue opened. That also happened to be the year of the first “talkie” or feature-length film with sound. That essentially killed silent films.

“The theatre organ was as quickly out as it was in,” Jones says.

Silent films held on for a couple of years, but after that the theatre organ was relegated to interlude music between features. Some found new life as novelties in restaurants or private homes — a blip in musical instrument history.

A Lost Art Back in Birmingham

The Mighty Wurlitzer’s return to its origin this weekend is due in part to Nathan Avakian. He’s a theatre organist and something of an evangelist for the instrument.

About 10 years ago, he was playing a theatre organ at someone’s home as part of a benefit in Portland, Oregon where he grew up. He was just 17. A local businessman and philanthropist named Jon Palanuk was there, and when he heard the music, it stopped him in his tracks.

“I was transported back to my childhood and blown away by how big and impressive and unique the sound of the instrument was,” Palanuk says.

He also noticed how many older people were in the room. A light bulb went off.

“I’m going to reinvent silent movies using theatre pipe organ music and reintroduce this sound to a whole new generation,” Palanuk says. He was determined.

“He was sure this was gonna work and so he actually approached me, introduced himself on the night of that fundraiser,” Avakian says.

This was Palanuk’s idea: filmmakers under the age of 20 would select one of several pieces Avakian composed for the theatre organ and create a three-minute silent film to go along with the music. That’s the basis of the International Youth Silent Film Festival.

It sounds simple, but it’s fundamentally different from the way films are typically made. Usually, a filmmaker starts with the pictures and adds music later.

“Having to go strictly based off audio is just so hard,” Birmingham-Southern College student Mackenzie Delk says. She and fellow student Cassady Quintana entered a film in the contest. They had a story in mind. They settled on one of Avakian’s pieces they thought would go with it best.

But Delk says they were practically in tears trying to make it work. They ended up reshooting part of their film. Still, Quintana says one thing about the silent film format was simpler.

“We didn’t have to worry about audio,” Quintana says. “So we could record in loud places anywhere that was making noise because we’re just taking the audio out so it doesn’t matter.”

For Nathan Avakian, it’s kind of backwards too. A composer usually writes to what’s already onscreen. In this case, he has no idea what he’s composing for.

“So rather than thinking about a specific plotline and imagining certain characters, I think of it more as just an interesting thematic piece of music,” Avakian says.

The contest uses 10 pieces from Avakian including western, film noir, horror, and romance.

The International Youth Silent Film Festival has run in Portland for a decade. And it’s the reason the Alabama Theatre’s Mighty Wurlitzer can return to its roots this weekend. Selections from that event will screen during the Sidewalk Film Festival and Avakian will be in Birmingham to accompany them live.

It’s the third year this has been part of Sidewalk.

“The very first time that they did this, the crowd went wild,” organist Gary Jones says. It’s the difference between watching a moving and live Broadway show Jones explains. “You’re part of that experience as opposed to, eh, I’ll just pop in a Blu-ray.”

Organizers in Birmingham and Portland hope in the next few years the Alabama Theatre can become a regional site for the silent film festival. In the meantime, aficionados say the theatre organ is not a historical blip, but a living, breathing instrument capable of contemporary sounds. They say the silent film should not be overlooked either.

The film “Overexposed” won first place at the 2019 International Youth Silent Film Festival.

WBHM’s Andrew Yeager watched many of the youth silent films. This one stuck with him.

Ok, one more …

Editor’s Note: The Alabama Theatre and the Sidewalk Film Festival are program sponsors of WBHM, however our news and business departments operate independently.

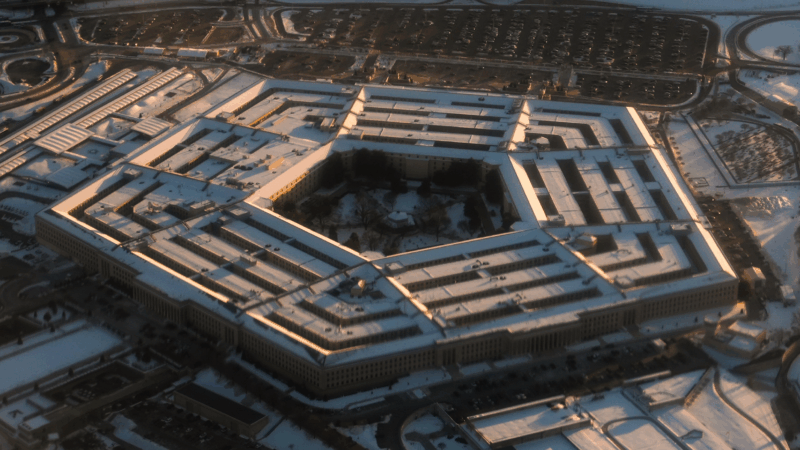

Pentagon puts Scouts ‘on notice’ over DEI and girl-centered policies

After threatening to sever ties with the organization formerly known as the Boy Scouts, Defense Secretary Hegseth announced a 6-month reprieve

President Trump bans Anthropic from use in government systems

Trump called the AI lab a "RADICAL LEFT, WOKE COMPANY" in a social media post. The Pentagon also ordered all military contractors to stop doing business with Anthropic.

HUD proposes time limits and work requirements for rental aid

The rule would allow housing agencies and landlords to impose such requirements "to encourage self-sufficiency." Critics say most who can work already do, but their wages are low.

Paramount and Warner Bros’ deal is about merging studios, and a whole lot more

The nearly $111 billion marriage would unite Paramount and Warner film studios, streamers and television properties — including CNN — under the control of the wealthy Ellison family.

A new film follows Paul McCartney’s 2nd act after The Beatles’ breakup

While previous documentaries captured the frenzy of Beatlemania, Man on the Run focuses on McCartney in the years between the band's breakup and John Lennon's death.

An aspiring dancer. A wealthy benefactor. And ‘Dreams’ turned to nightmare

A new psychological drama from Mexican filmmaker Michel Franco centers on the torrid affair between a wealthy San Francisco philanthropist and an undocumented immigrant who aspires to be a dancer.