Teaching Bleeding Control as a Survival Strategy

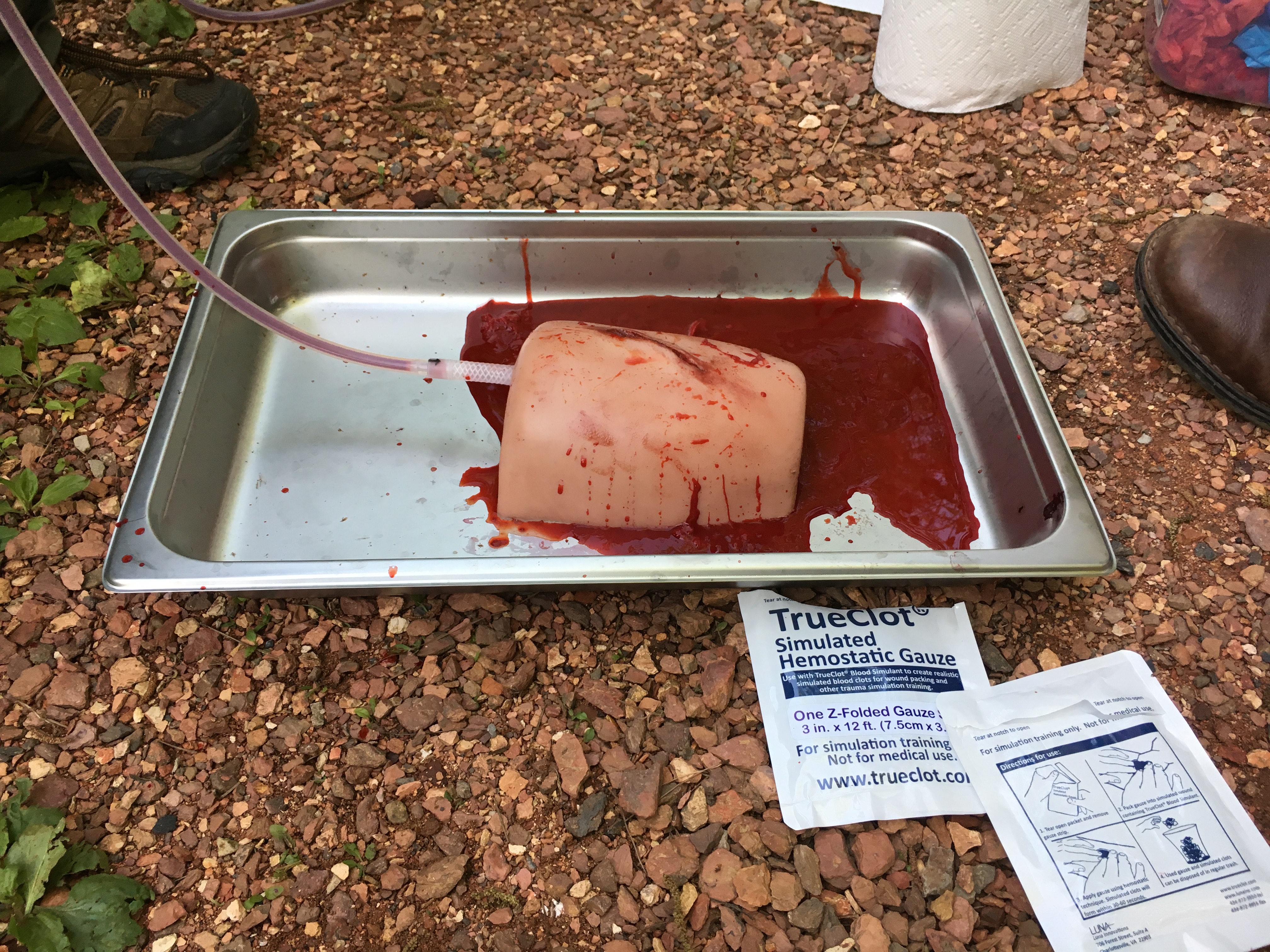

Anne Balch packs a simulated gunshot wound with clot-inducing gauze behind the Ruffner Mountain Nature Center.

Recent mass shootings have prompted more debate around gun control, but they’ve also sparked interest in practical ways to keep people alive in those critical moments after a tragedy. Victims can die from uncontrolled bleeding in as little as five minutes. That’s often before trained responders arrive. But by teaching regular people to stop the bleeding, just as with CPR or the Heimlich maneuver, people can save lives.

That’s why on a recent Saturday, there’s a gruesome-looking scene behind the Ruffner Mountain Nature Center. After practicing with tourniquets, a half-dozen students — first responders and regular people — stand over bleeding control kits and pans holding what look like bloody cuts of meat. But they’re actually simulated human thighs with different injuries.

I joke that they’re real human body parts. Dr. Lee Burnett, a UAB oncologist and outdoorsman who’s leading the course, tells me they are actually molded from real humans. Then he asks the group, “who wants to go first?”

Anne Balch, Ruffner Mountain’s office manager, steps up. She says she wants to learn how to pack wounds because so many people hike out into the rugged reserve.

Burnett points to one of the two pans. “Here’s a deep laceration … and that one’s a high-velocity gunshot wound, with the femur involved. Which person would you care to help first?”

Balch chooses the gunshot wound. Burnett, who helped found the Alabama Wilderness Medicine Association and teaches all sorts of life-saving techniques around the state, squeezes a plastic bottle connected to the fake thigh by a tube. Very realistic fake blood starts spurting out of the hole. The joking stops. Balch kneels down and gets into a quick two-handed rhythm: apply pressure, pack gauze, apply pressure, pack gauze.

“Looks like you’ve done that before,” says Burnett.

“Absolutely not,” replies Balch with a laugh.

The fact is, most people are unprepared for situations like this, says Burnett. But this course is one effort to change that.

“Las Vegas, the Boston Marathon bombing – you aren’t going to have enough professional medical care providers to address all the people who might need assistance,” he says. “The more people who are trained and prepared, the better.”

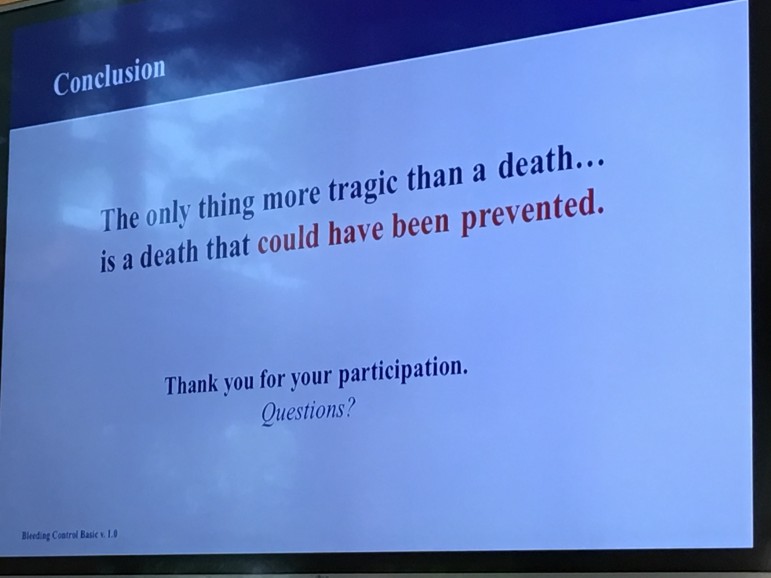

Put another way, according to BleedingControl.org — an effort by the American College of Surgeons and other groups to teach the public these emergency techniques — “the only thing more tragic than a death from bleeding is a death that could’ve been prevented.”

Burnett reminds the class about something he’d said earlier: though it might be tempting, do not let up on the pressure or unpack the gauze to check the wound – that could interfere with clotting.

But Balch is clearly using good technique. Burnett gives the fake blood bottle another squeeze.

“And at this point squeezing the bottle, I’m finding it difficult to get anything to get out.”

Balch’s pressure and the clotting have basically stopped the bleeding.

Burnett reviews the “ABC’s” of bleeding control. Once the situation is safe, “A” means “alert”: call for help if you can. “B” is for bleeding, as in, find the source, which is not always easy when there’s blood all over or when the main wound is under someone’s clothes. “C” is for “compress”: use direct pressure, tourniquets, or both.

“The stop the bleed program is definitely worthwhile,” says Wes Ward, emergency medical services training officer for the Center Point Fire District. He’s taken and given courses like Burnett’s. The bleeding control techniques can be used with improvised materials — like belts for tourniquets or clean cloth for gauze — but kits with specially designed field tourniquets and hemostatic gauze that speeds clotting make saving lives more likely.

“[We] probably need to work towards committing public funding to having these kits available in public places in the same way that we did 10 or 20 years ago with public access to defibrillators,” says Ward.

Last year Georgia set aside a million dollars to put almost 30,000 bleeding kits in its public schools — roughly a dozen in each building. In Alabama, it’s more district by district, but Ward, Burnett and many of their colleagues hope it’ll go statewide, because the need doesn’t appear to be going away.

Web-exclusive tips from Dr. Burnett’s bleeding control course:

“The fundamental principle for hemorrhage control: First off, don’t create another victim. Be aware of potential dangers to you as a well-intentioned assistant. If that’s on the side of the road, you do not need to get hit by a car in your attempts to get to someone else. If it’s a violent scenario, again, wait until there’s a reasonable chance to intervene without exposing yourself.”

Not as Easy as it Sounds

“Discover the source of the life-threatening bleeding. This may require you to remove clothing or to cut clothing. If you’re cutting clothing, especially blood-soaked clothing, be very careful not to cut the patient.”

Understand Your Own Reactions, and the Victims’

“Blood is always disturbing. Most people have a visceral recoil reaction to blood, and some people have a more dramatic reaction. But again, look for life-threatening bleeding — look for blood that actually has enough velocity and volume to spurt. Look for blood as it continues to come from the wound. If it makes a puddle on the ground, it’s quite possibly life-threatening. If clothing is saturated, it’s probably life-threatening. If there is an amputation or a near-total amputation of an arm or leg, that’s life-threatening. And bleeding in a victim who’s now has altered mental status, they’re confused or unconscious, have a very high suspicion for life-threatening bleeding.”

Improvise Gauze: Infection Is Better than Death

“What do you do if you don’t have a trauma first aid kit? Use any clean cloth or gauze to provide steady pressure directly on the wound. Now how clean is clean? Clean means clothing-clean. You wouldn’t want to use muddy, dirty, fouled clothes if at all possible. On the other hand, a patient will die far quicker of exsanguination than from infection, and bacterial exposure can be addressed with post-exposure prophylaxis and antibiotics. So, use your shirt. Use the patient’s shirt. Handkerchiefs, bandanas, anything available. And steady pressure directly on the wound.”

Use Gravity, Give Warnings

“It’s going to be hard for you to hold steady pressure for the minimum of five minutes necessary to really have the opportunity to initiate a clotting cascade. Because of that, let gravity work for you. Whenever you can lean with locked joints on a patient and just let your body weight put the pressure on them, that’s going to be superior. And that’s going to hurt. You know, you need to be prepared for it. This is going to cause pain for the victim. Let the victim know, ‘this is going to hurt,’ if they’re conscious, because a lot of times people are more frightened by unexpected pain than by engaging with pain that they were expecting.”

How to Use a Tourniquet

“Put it above the source of the bleeding, generally two to three inches above the wound. But do not put the tourniquet directly over knees or elbows. Your knees and your elbows form a bony cage and the arteries and the nerves and the veins go through that, so you can tighten that tourniquet as tight as you can and blood will still be pumping through. And do not put it over clothing that has a pocket with things in it. Somebody’s wallet or whatever it is could interfere with tightening. So just empty the pocket, or remove the clothing.”

“And, how tight do you need to get a tourniquet? Until the bleeding stops. That’s the right answer. You will know when it’s tight enough. Unlike direct pressure, where you aren’t supposed to stop and check, a tourniquet gives you immediate feedback. You KNOW you did it right. And also, unlike direct pressure where you know, once you start putting direct pressure on somebody, you’re obligated to stay there for a good long while, once you staunch the bleeding with a tourniquet, you now are capable of moving on to the next victim.”

Rebecca Gayheart Dane on caring for her late husband, Eric Dane, and synthetic voices

The wife of 'Grey's Anatomy' actor Eric Dane says caring for him gave her an "extra dose" of compassion for others.

Chile turns right: Kast inaugurated as nation’s most conservative leader since Pinochet

Chile has sworn in its most right-wing president in decades — and his rise, and ideology, are rooted in a small town beneath the Andes.

Iran’s soccer team cannot participate in the FIFA World Cup, Iranian minister says

Iran is set to play three games in the U.S. this June. But amid the U.S.-Israel military campaign that has killed Iran's supreme leader, Iran's sports minister said the team would pull out.

Pentagon probe points to U.S. missile hitting Iranian school

A military assessment suggests a U.S. Tomahawk cruise missile was responsible for at least 165 deaths at an Iranian girls' school, according to a U.S. official who was not authorized to speak publicly.

Harrison Ford isn’t retiring: ‘I really wouldn’t know what to do with myself’

Ford struggled to find his footing in Hollywood before being cast as Han Solo in Star Wars. Now 83, he plays a therapist in the Apple TV series Shrinking: "I really do love the work," he says.

No Nobles Day: Britain’s Parliament boots its last hereditary Lords after 700 years

Government minister Nick Thomas-Symonds said the change put an end to "an archaic and undemocratic principle." The removed aristocrats are 92 of the House of Lords' 800 members.