Concussion Expert on Youth Sports: “Time to Make Some Decisions”

It’s football season, which has increasingly become a time of unease for parents of young athletes struggling with a dilemma: to play, or not to play. Between the contact sports all around us and a recent study linking adolescent concussions with multiple sclerosis, WBHM’s health and science reporter Dan Carsen wanted to check in with an expert. Brain injury specialist Dr. Elizabeth Sandel has been studying brain trauma for more than three decades. Below are takeaways from their conversation.

Concussions and Multiple Sclerosis

The study published in Annals of Neurology found that one concussion in adolescents increased their risk of developing MS later in life by about 22 percent on average. That increase rose to about 150 percent with multiple concussions. Researchers analyzed data from more than 7,000 Swedish men and women diagnosed with multiple sclerosis between 1964 and 2012. Each was compared to at least 10 other Swedes of the same age, gender, and county of residence. Overall, the the study included data from more than 80,000 people.

Dr. Sandel has no connection to the study, but she says, “It’s quite fascinating. They looked at this very large set of data and then they did a very good job — a very well designed study. And what they found was an increased risk for MS for the adolescents, 11-to-20 year olds. And then they found a ‘dose relationship’: if the subjects had more than one concussion, they were at even greater risk for development of multiple sclerosis.”

“It links in some ways to some of the other studies being done on things like chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), Parkinson’s disease, Lou Gehrig’s disease, and all these neurodegenerative conditions, because it seems as though the concussion is a trigger for biochemical changes in the brain that then cause, in the case of MS, an autoimmune attack on the myelin. That’s the insulation on the axon, that part of that nerve, the neuron. So they’re similar in terms of this trigger, which seems to be a brain injury — in this case a mild brain injury or concussion.”

More than Football, and Helmets Don’t Help

Sandel says she’s been exploring this issue her whole career but accelerated the exploration because she’s writing a book on it. “NFL players in that continuing study — a huge percentage [had CTE], and neuroimaging suggested that even when symptoms resolved, there could still be brain changes that occurred because of the trauma. I am increasingly concerned, and not just about football. With children and youth primarily, but young adults too, I’m concerned about the collision sports. I’ve almost come to the conclusion that we should not be exposing our children and adolescents and young adults.”

She explains that the issue is not so much direct impact to the head, although that can certainly cause brain trauma. It’s more often the sudden stopping or direction-change that slams the brain into the inside of the skull. That’s why the best possible helmets can help only a little when you have sudden, hard body-to-body or body-to-ground contact: the helmets are not inside the jerked head.

Sandel adds, “I’m very concerned and I think it’s time for more and more conversation on that. Certainly I’m not against physical activity in children. There are plenty of ways to get physical activity and the benefits of it. But we don’t have to have our children engaged in collision sports that put them at really high risk. And every time they have a concussion and we return them to play, they’re at significantly increased risk of second or third or fourth concussion. It’s really a national crisis, and we need to all be paying attention and involved in trying to promote the research that we need, but also keep our kids out of harm’s way.”

Real Brain Damage

Sandel says doctors and researchers used to think that concussions were strictly functional brain issues, reasoning that since, in most cases, no major damage was detectable and many people seemed to recover, there was no real physical damage. But she says, “we now know that’s false.” There are microscopic changes not seen on CT scans, but are detectable through sophisticated MRI studies and PET scans. “We can see abnormalities. So we have to stop saying there’s no damage. There’s damage,” she says.

When Your Kid Hits Her Head

Though it’s not easy, Sandel says parents of athletes who’ve been injured should keep several things in mind and, “use the opportunity to educate at the same time you’re watching and trying to discern what’s going on with the child. And if there is any thought that they may have had a concussion, they need to be taken to see a physician. That’s clear. But I think it’s an opportunity: kids don’t know a lot about concussions, and I think we’re not doing a super job with education, so they might not know what the symptoms are. The key is not to dismiss but rather to use it as an opportunity, a chance to educate about the symptoms of concussion and about the importance of their brain for what they’re doing now, and what they’re going to be doing in the future.”

“I also think they need to be aware that it’s time to make some decisions. It’s still not clear whether one concussion is too many. Once it’s two concussions, I do believe it’s too many. We don’t have good guidelines on retiring children or adolescents from play. There’s a lot of talk about a removal from the game, but there’s not a lot of discussion on the guidelines about retiring from play. So all of those are really important.”

And in the big picture, she says, “This means that parents, as well as the schools, are going to need to be really up to speed in terms of their knowledge of concussions, because frankly there aren’t a lot of athletic trainers in the schools. They’re coaches, but they’re not athletic trainers and people skilled at diagnosis. So a lot is going to be important in terms of the parental role. And I do think PTAs might be a great place where the educational programs could happen.”

Theere’s No Blood Test, So Some Symptoms To Watch For

“Concussions are a symptom-based diagnosis,” says Sandel. “We do not have biomarkers, we don’t have a way to diagnose this, so what we need to be doing is educating our kids about what to look out for. Most sports-related concussions don’t involve loss of consciousness. So they need to know that confusion, or problems with memory, or just having a little disorientation and not knowing what day it is, or what game they’re playing, or who the opponent is and so forth — that kind of confusion is certainly key. Headaches. They might experience double vision or blurred vision, sensitivity to light or to sound, and then they might be having some balance problems. And that’s another thing that parents can pretty easily tell. Kids might also have trouble sleeping, and then they might start having struggles with their academic work. And there could be other reasons for that, but I think it’s important for the parents to be vigilant, and again, to educate.”

“The CDC has some excellent material for the schools and for parents. “People need resources and they need people to interpret what is out there in terms of the research, not putting people into a panic, because again, these are suggestions and associations and not definitive research at this point. But I do think the dialogue must continue. The education must continue. And I think that’s one of my purposes at this point in my career.”

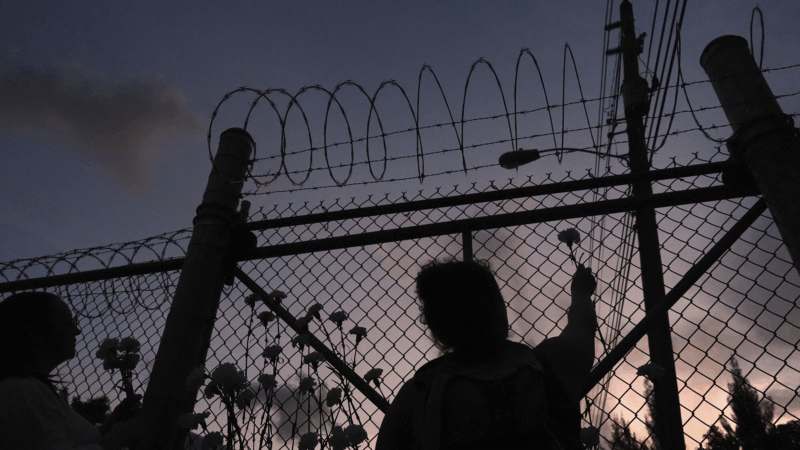

Immigration detention on track for deadliest fiscal year since 2004

Twenty-three people have died since October in ICE custody, as advocates warn about overcrowding and health care access.

Photos from Iran and across the Middle East as the war enters Week 2

More than a week of the U.S. and Israel's war against Iran has dragged in global powers, upended the world's energy and transport sectors, and brought chaos to usually peaceful areas of the region.

‘American Classic’ is a hidden gem that gets even better as it goes

In this charming TV series, Kevin Kline plays a Shakespearean actor who retreats to his small hometown after a crisis, and gets engaged in an effort to save the local theater.

A dose of psilocybin helps smokers quit in new study

The psychoactive substance in magic mushrooms appears to have a powerful effect on people trying to stop smoking.

‘Pro-worker AI,’ streaming fatalities, and other fascinating new economic studies

From artificial intelligence to fatalities from music streaming to the effects of immigrants on elderly health care, the Planet Money newsletter rounds up some interesting new economic studies.

GLP-1s have transformed weight loss and diabetes. Is addiction next?

A large study found that people taking GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic for diabetes were less likely to be diagnosed with substance use disorder.