Birmingham Revitalization: An Alternative Model from Cleveland

When a city neighborhood rebounds, it’s typically a story of investors buying cheap property, building, and then attracting new residents. That runs the risk of pushing out current residents, who are often poor.

As part of our series on Birmingham’s revitalization, we take a look at an example of an alternative model: worker cooperatives. These are businesses owned and controlled by their employees. These arrangements are more common in Europe. For instance, the Spanish co-op Mondragon Corporation has grown into a multinational conglomerate.

In the U.S., a group in Cleveland, Ohio, tried to use worker cooperatives to revitalize a depressed part of that city in the late 2000s. Journalist Steve Friess wrote about the cooperatives’ track record for the online news site Take Part.

The Great Fanfare

The idea caught the media’s imagination. It was hailed as the “Cleveland Model.” With backing from the city, the philanthropic community and other investors, Evergreen Cooperatives launched three companies: a solar power operation, a hydroponic lettuce growing facility and an industrial laundry service.

“In theory, the universities and the hospitals will need lettuce. They will need laundry,” says Friess. By contracting with these local “anchor institutions,” the co-ops could grow their businesses and provide jobs to unemployed and underemployed residents.

“Not only are they working for a reasonable wage, but they’re also, in theory, gathering some equity in the companies that they’re working for,” says Friess.

Residents would now have resources to improve their lives and their neighborhoods. The co-ops would spur more co-ops.

But when Friess looked into the businesses in 2014, he found something far short of that vision.

The co-ops had spent about $25 million and employed about 90 people. That’s in an area with about 44,000 residents living in poverty.

“These opportunities were extremely scarce,” says Friess.

Vision vs. Reality

Friess says despite the involvement of smart businesspeople, they missed a few basic things.

They assumed the hospitals would need laundry services. In actuality, the hospitals were under long-term contracts they couldn’t break.

“They were able to peel off little pieces of it,” says Friess. “But there was no real way to just give this small startup all of its business.”

Similarly, these institutions could buy lettuce from California growers for less than what the Cleveland operation could offer.

Friess said organizers also didn’t plan for scaling up their businesses. So once they maxed out their capacity for laundry, for instance, they couldn’t grow anymore without building more facilities with more investor money.

“In a lot of ways the hype on this operation, the hype on what was going on in Cleveland, got way ahead of the reality,” says Friess.

Lessons Learned

Friess says the underwhelming results of the Cleveland cooperatives are partly a result of poor business decisions, such as putting people with no industry experience in charge.

“At first, the person who ran it [the laundry operation] had never run a laundry before,” says Friess.

But he says there were more fundamental flaws.

When the Mondragon Corporation started in the 1950s, banking was different.

“They lived in an era where they could create their own banks and they could create their own terms and there wasn’t that much regulation,” says Friess.

He says under current U.S. banking rules, it would be very difficult to repeat what the Spanish company did.

The Cleveland co-ops posed another conundrum as a neighborhood revitalization effort: residents who did get jobs and improved their lives moved out of the neighborhood.

“It’s interesting to academics, interesting to other cities looking in,” says Friess. “But I don’t know that there is much evidence right now that this operation has made any significant difference to the city at large.”

Prediction market trader ‘Magamyman’ made $553,000 on death of Iran’s supreme leader

It's the latest trade drawing scrutiny on the popular prediction market site for appearing to show an insider making profits on military secrets.

Oil prices rise sharply in market trading after attacks in Middle East disrupt supply

The high prices came as U.S. and Israeli attacks on Iran and retaliatory strikes against Israel and U.S. military installations around the Gulf sent disruptions through the global energy supply chain.

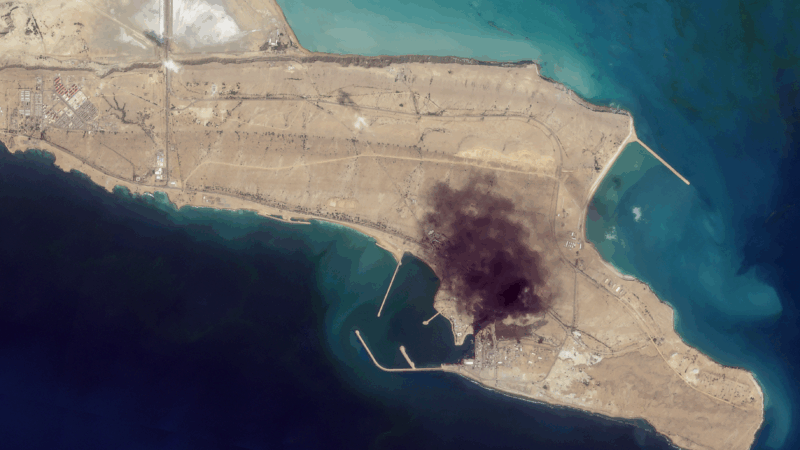

Satellite images provide view inside Iran at war

Satellite images from commercial companies show the extent of U.S. and Israeli strikes, and how Iran is responding.

Mideast clashes breach Olympic truce as athletes gather for Winter Paralympic Games

Fighting intensified in the Middle East during the Olympic truce, in effect through March 15. Flights are being disrupted as athletes and families converge on Italy for the Winter Paralympics.

A U.S. scholarship thrills a teacher in India. Then came the soul-crushing questions

She was thrilled to become the first teacher from a government-sponsored school in India to get a Fulbright exchange award to learn from U.S. schools. People asked two questions that clouded her joy.

Sunday Puzzle: Sandwiched

NPR's Ayesha Rascoe plays the puzzle with WXXI listener Jonathan Black and Weekend Edition Puzzlemaster Will Shortz.