Kidney Chain Links Record Number of Donors and Needing Patients

Traditionally, people who suffer from kidney disease and need a transplant put their name on a national list. Next, they have to wait until their name comes up to receive a compatible kidney. And with over 100,000 names on that list, it can take up to 10 years to receive a kidney. Today, there’s a viable alternative. The University of Alabama at Birmingham is at the forefront of a process, which allows someone to receive a healthier kidney in a much shorter time. Les Lovoy reports on the Kidney Donor Chain.

Robbie Butler lives in Lanett, Alabama. It’s about two hours southeast of Birmingham. With a population of 6,500, it’s a safe bet most folks living there know each other. When Butler was 10, James Oliver started dating his older sister. Butler says Oliver became like a brother; taking him fishing, and to his softball and pick up football games. Their close relationship is the reason Butler finds himself lying in a UAB hospital bed, being prepared for surgery.

In less than an hour, he’ll have one of his kidneys removed to be transplanted in another patient. Butler wanted to donate a kidney to his life-long friend who just now happens to be his brother in law.

“His kidney started failing for the second time, this is his second kidney,” explains Butler. “He got lucky the first time. He really didn’t have to wait too long. But, this time, we kind of knew he was going to need some help. So, I wanted to do my part and get tested.”

But when Butler visited UAB, tests showed his kidneys weren’t compatible with his brother-in-laws. The staff did tell him, however, there was an alternative. Both he and his brother-in-law could become links in UAB’s kidney donor chain. Here’s how it works. Someone wants to donate a kidney to a close friend or family member. But, kidneys aren’t interchangeable. Sometimes donors and recipients are incompatible for various reasons. So, in order to become a link in the chain, the donor will give their kidney to a total stranger.

Back to Robbie Butler. Since he couldn’t donate his kidney to his brother in law, Butler volunteered to donate a kidney to someone he never met. Franck Southon is at the other end of the hall on the morning of the surgery. He’ll receive a kidney from Butler. Southon is originally from France. He came to the United States and swam for the University of Alabama. Last year a friend visited his family during the holidays and saw his dialysis machine.

“Working in the medical field, she knew what it was,” Southon remembers. “And, so she started asking my wife what was going on and I guess she told her. After a week or so later, she said I want to give my kidney to you.”

As you might have guessed, her kidneys were not compatible with Southon’s. But, like everyone else in this story, she wanted her friend, Franck to receive a new kidney as soon as possible. She volunteered to donate a kidney to a stranger. That allowed both she and Southon to be links in the chain, and that’s how Southon ended up at the end of the hall, preparing to receive a kidney donated by Butler.

“Just unbelievably thankful and very very grateful,” says Southon. “Blessed that she even offered to do such a thing. Having a living donor is such a gift, but having the kidney pair, enable the donor to give that kidney to me, is invaluable.”

When someone dies, there are certain metabolic changes to blood and tissues, which make the kidney less healthy. Dr. Dorry Segev teaches and practices transplant surgery at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

“A live donor kidney transplant will last about twice as long as one that comes from a deceased donor,” Segev notes. “And, you don’t have to wait on a list behind thousands of other patients.”

Dr. Jayme Locke is an assistant professor of Surgery at UAB and spearheads the Kidney Donor Chain. To date, a record 29 kidneys have been donated and transplanted in this particular chain. That the current chain only involves UAB is also rare — most kidney donor chains cover different hospitals in different states. What sets UAB’s program apart, is that they offer specialized services, which helps patients overcome some of the incompatibility barriers associated with a kidney transplant. Those services are a result of money, planning and infrastructure. Additionally, Dr. Locke says there’s something unique about Southerners and Alabamians who have made this kidney donor chain so successful.

“What we have here is a real sense of community, that I really haven’t experienced anywhere else,

Dr. Locked explains. “And, they really want to come through on their word and give back to the community and see themselves as one big extended family. And, I think that’s what’s really keeping these folks in the game, which is allowing us to help so many people than most of the other chains that have ever been done in the country.”

Just this week, two more transplants will be donated, which will make 30 and 31 donations. And on December 18th, transplant number 32 will be performed. Dr. Locke and her associates plan to restart the chain in 2015, giving even more patients a future they weren’t sure they were going to enjoy.

Supreme Court appears split in tax foreclosure case

At issue is whether a county can seize homeowners' residence for unpaid property taxes and sell the house at auction for less than the homeowners would get if they put their home on the market themselves.

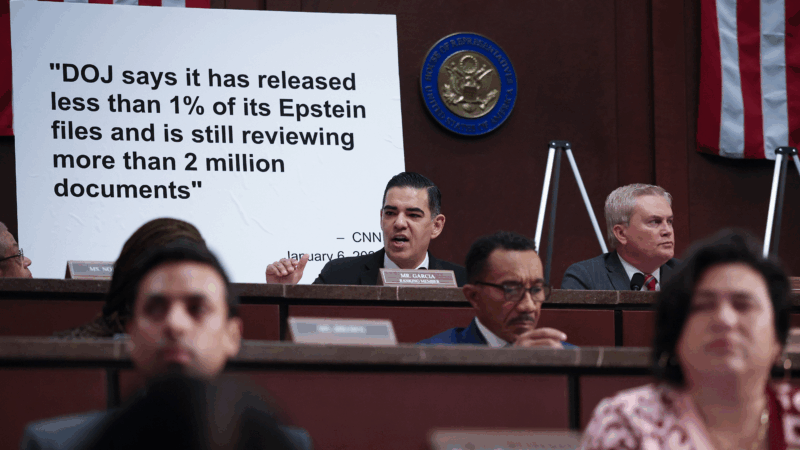

Top House Dem wants Justice Department to explain missing Trump-related Epstein files

After NPR reporting revealed dozens of pages of Epstein files related to President Trump appear to be missing from the public record, a top House Democrat wants to know why.

ICE won’t be at polling places this year, a Trump DHS official promises

In a call with top state voting officials, a Department of Homeland Security official stated unequivocally that immigration agents would not be patrolling polling places during this year's midterms.

Surgeon general nominee Means questioned about vaccines, birth control and financial conflicts

During a confirmation hearing, senators asked Dr. Casey Means about her current positions and her past statements on a range of public health issues.

Kalshi reveals insider trading case against editor for MrBeast

With prediction markets booming, so have concerns about insider trading. Now, Kalshi has disclosed its first public actions against accounts suspected of trading on confidential information.

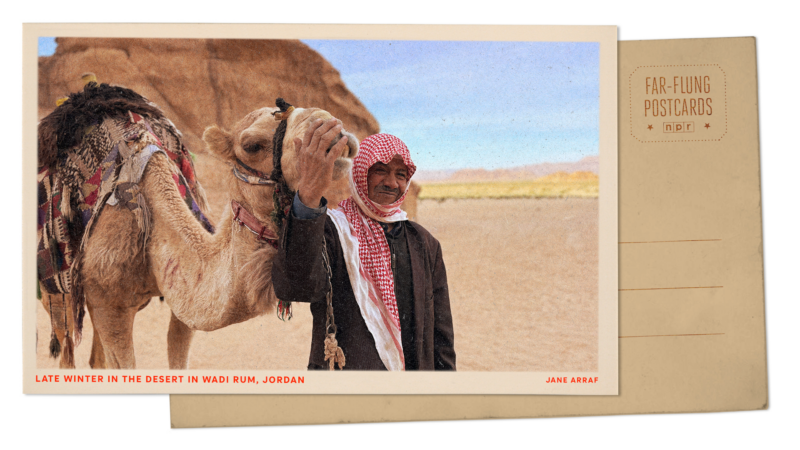

Greetings from Jordan’s Wadi Rum desert, where patches of green emerge after winter rains

Wadi Rum's otherworldly landscape is where Star Wars movies and The Martian were filmed. In late winter, plants emerge in this desert — but some are toxic to camels, so their herders must protect them.