Remembering the Stand in the Schoolhouse Door

Some images from the civil rights era are indelibly etched on our collective memory. For instance, the rubble left by the bombing of the 16th St. Baptist Church or the dogs and fire hoses set upon marching children in downtown Birmingham. Tuesday marks the 50th anniversary of a third — Governor George Wallace’s stand in the Schoolhouse door.

George Wallace’s stand was not a spontaneous event. Wallace carefully choreographed the scene to keep a campaign promise to his political base, a promise to defy federal desegregation orders. After years of delay and many federal court orders, the Kennedy administration was determined that black students Vivian Malone and James Hood would attend the university. And they let Wallace know they were serious.

“Attorney General Robert Kennedy himself visited Gov. Wallace in Montgomery on April 15.”

Culpepper Clark is a former dean at the University of Georgia. He’s author of The Schoolhouse Door; Segregation’s Last Stand at the University of Alabama. Clark says the Kennedy Administration wanted to avoid a repeat of the riot that killed two people at Ole Miss when that school was integrated the year before. When Robert Kennedy reached out to Wallace, he was taken aback by the Governor’s response.

“When Dynamite Bob Chambliss and accomplices bombed the 16th St. Baptist Church, Wallace went out and apologized not for anything but blamed it on the African American Community itself.”

The stand in the schoolhouse door helped propel Wallace to run for president 4 times. During a Maryland campaign stop on May 1972, Arthur Bremer shot the governor. That assassination attempt left Wallace to spend the rest of his life in a wheel chair.

The Effect of the Stand

It was Wallace’s success at attracting white working class voters that changed America’s political landscape.

“I think Wallace’s lasting legacy is the polarization that has made Alabama to this day not only the most conservative of American states but also most racially polarized.”

Wayne Flynt is a former history professor at Auburn University and is the author of Alabama: The History of a Southern State.

“In the 2008 presidential election between Obama and John McCain Alabama had the most divided populace of any state in the United States. 98% of African Americans voted for Barack Obama and more than 90% of whites voted for John McCain.”

Culpepper Clark believes the most consequential effect of Wallace’s stand was the shift in American political power.

And he carved out of the Democratic Party what would become known as Wallace Democrats. These Wallace Democrats would eventually become the Reagan Democrats of the Reagan revolution of the 1980s. Thus there’s a direct line between the drama that was taking place, the political theater. But behind it was a whole political sea change and the Democratic Party would lose its base for a long time to come.”

George Wallace’s stand didn’t stop Vivian Malone. She graduated from the University in 1965. James Hood left the university in ‘63 but went on to earn graduate degrees from Michigan State and Cambridge University. By 1966, there were 400 black students attending classes on the 3 campuses of the University of the Alabama System. For WBHM, I’m Greg Bass.

~Greg Bass, June 11, 2013

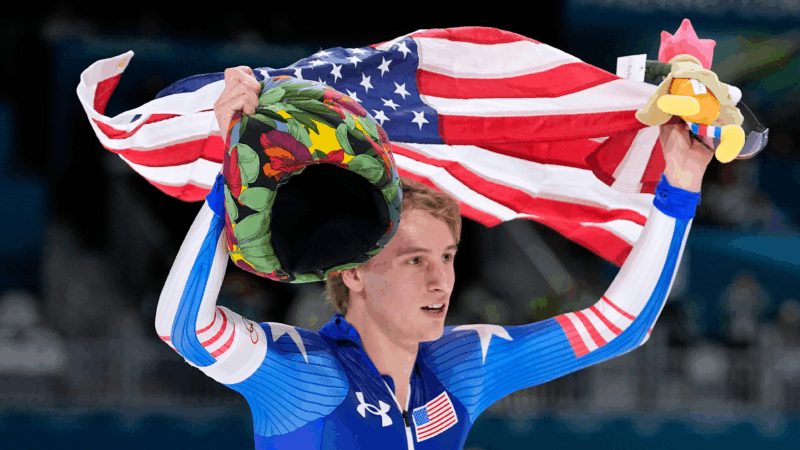

Jordan Stolz opens his bid for 4 golds by winning the 1,000 meters in speedskating

Stolz received his gold for winning the men's 1,000 meters at the Milan Cortina Games in an Olympic-record time thanks to a blistering closing stretch. Now Stolz will hope to add to his collection of trophies.

How the FBI might have gotten inaccessible camera footage from Nancy Guthrie’s house

Last week, law enforcement said video footage from Nancy Guthrie's doorbell camera was overwritten. But the FBI has since released footage as Guthrie still has not been found.

How to hone your ‘friendship intuition’

Friendship expert Kat Vellos shares tips on how to make a new friendship stick, including what to do together, how often to hang out — and what to do if the vibes just aren't there.

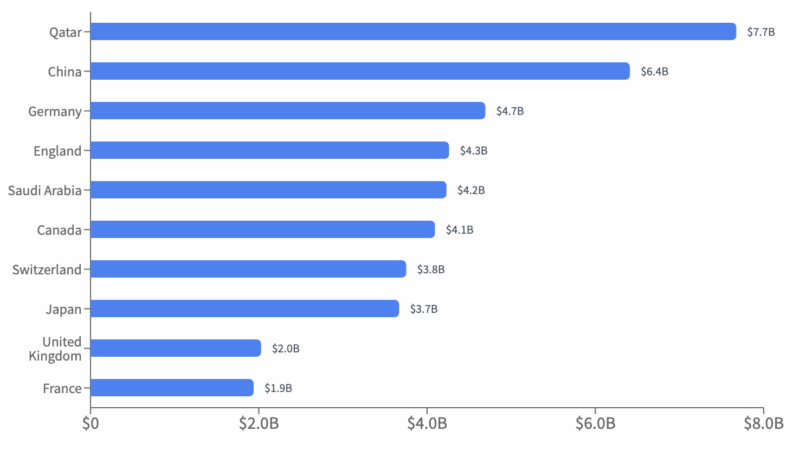

US Colleges received more than $5 billion in foreign gifts, contracts in 2025

New data from the U.S. Education Department show the extent of international gifts and contracts to colleges and universities.

Free speech lawsuits mount after Charlie Kirk assassination

Months after the killing of Charlie Kirk, a growing number of lawsuits by people claim they were illegally punished, fired and even arrested for making negative comments about Kirk.

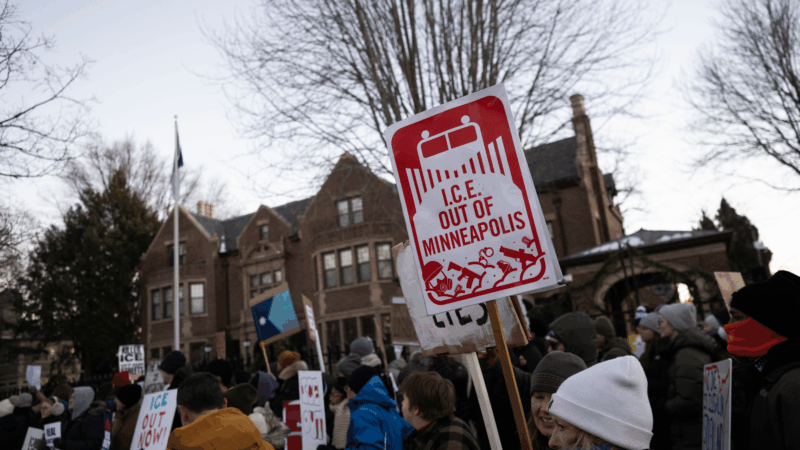

Swing voters in Arizona say they want to see ICE reformed

Concerns about the tactics of federal immigration agents remain front of mind for some key voters who supported President Trump in 2024.