Charter Schools: None in Alabama, but May Change Soon

Alabama One of Just Nine States Without Charter Schools

State Leaders and Advocates Look to Change that, Soon

Dan Carsen, Jan. 17, 2012

In a national ranking on charter schools being released today, Alabama did not even come in last. That’s because the state is one of nine that does not have charter schools or a law that would allow for them. But the Republican-dominated state legislature, with support from the governor and opposition from Alabama’s most powerful teacher’s organization, is looking to change that in the coming session that starts Feb. 7.

“I think it will be bipartisan,” says Alabama House Speaker Mike Hubbard (R-Auburn). “Educating kids, doing what’s right, isn’t a partisan issue …. We’re late to the game, and that’s a good thing. We can pick and choose. We don’t have to replicate mistakes, and we can copy from what works.”

Charter schools are publicly funded elementary or secondary schools that don’t have to follow the same rules as regular public schools. But charter schools must translate that flexibility into certain results – specified improvements in test scores, or improvement in school discipline, for example – set forth in their charters. The schools are established and attended by choice.

According to Todd Ziebarth, vice president of the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, “After 20 years of lessons learned and positive results in the national charter school movement, it is time for Alabama to enact a strong charter school law that provides more high-quality public school options to its students, particularly those who are struggling in their current school.”

Representative Hubbard recently visited charter schools in Memphis that he described as successful:

“They cut through a lot of bureaucracy and red tape. The school staff can structure their academics and curriculum. The principal is empowered to make those and other decisions, and teachers don’t have tenure. But [the schools] have no problem finding teachers.”

Alabama Education Association (AEA) vice president Anita Gibson sees the situation differently. “Governor [Robert] Bentley already wants to take $400 million out of the Education Trust Fund to balance the General Fund Budget. There should be no funding for charter schools when we don’t have enough money for the regular schools that already exist,” she says, adding, “Charter schools do not outperform regular schools if regular schools are given the same amount of freedom to be creative. When you think about it, charters are a way to resegregate the schools, by haves and have-nots.”

Gibson also questions the feasibility of charter schools in such a rural state, given transportation issues and the availability of viable choices in low-wealth, low-population districts. Even some charter advocates concede those rural hurdles, but point out that places like Birmingham and other urban areas would not face the same drawbacks.

But Gibson sees dollar signs behind the coming push for charter schools. “My personal view is that people want to contract out their services. There’s a lot of money to be made in educating children. That’s not everybody who favors charters schools, but that is one of the keys.”

AEA spokesman David Stout elaborates. “The best studies prove that charter schools are not a panacea … We know what works. We need an intervention program to turn around poorly performing schools, but it needs state funding. The Alabama Reading Initiative works and has increased reading scores, but it needs to be protected. The Alabama Math, Science, and Technology Initiative (AMSTI) is a highly acclaimed program with proven success, but is it in less than half of Alabama schools … Alabama’s pre-K program is one of the best in the nation, but only about five percent of students are served. The question is, why don’t we fund the … programs we know work?”

There is a wide and growing body of research on charter schools, and those involved in the debate can quote findings that are positive, negative, or mixed. Education policy experts generally agree that some charter schools have been successful, while others have been failures, and that the variables behind their relative success are often as complicated as education itself.

Sally Howell, director of the Alabama Association of School Boards, reflects that complexity and takes a more measured approach. “We need to move slowly and prudently, and we need to guarantee quality,” she says. “We need to determine what the real issues hurting our schools are, and then make sure any bill is narrowly tailored to address those needs.”

She adds, “Charter schools need to be locally chartered, be open to the same populations as [nearby] regular schools, meet basic accountability, financial reporting, and safety standards … and school boards need to be able to petition for relief [if a charter school is failing]. If a charter school closes, the kids go back to a regular school. And whatever advantage charter schools offer – wouldn’t you want that for all children?”

Advocates in Alabama have blamed the state’s failure to secure federal Race To The Top funding on the lack of charter schools. But based on the scoring system used to award those funds, Alabama wouldn’t have received the money anyway due to low scores on other criteria, including core standards in line with national standards, and alternative pathways for training and certification of principals and teachers. Only 11 states – including Georgia and Tennessee – and Washington, D.C., were awarded RTTT money. All of them have charter schools.

The debate over charter schools isn’t new in Alabama. A 2010 bill to allow them failed in the state legislature. At the time, the body was controlled by Democrats, and the AEA opposed the bill. WBHM produced a series on charter schools, including “Charter Schools 101.”

The eight other states without charter school laws are Kentucky, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, Washington, and West Virginia. According to the third annual NAPCS report released today, the top 10 states that “best support the growth of higher-quality charter schools” are Maine, Minnesota, Florida, New Mexico, Massachusetts, Indiana, Colorado, New York, California, and Michigan. Mississippi was ranked last.

The report comes just before “National School Choice Week” begins Jan. 22. The NAPCS is a national nonprofit committed to advancing charter schools. For more information or to see the report, click here.

Photo by B. Brown, courtesy of Flickr

Also from Dan Carsen: Bards of Birmingham.

You may also like: Religious Exemptions to School Vaccine Requirements on Rise, or: School Transportation Safety – Part Three: Walking School Bus.

In Vermont, small town meetings grapple with debate on big issues

Typically concerned with local issues, residents at town meetings in Vermont and elsewhere increasingly use the forum to debate polarizing national and international events.

Alabama man, on death row since 1990, to get new trial

The U.S. Supreme Court on Monday declined to review the summer ruling from the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. The decision paves the way for Michael Sockwell to receive a new trial.

Supreme Court blocks redrawing of New York congressional map, dealing a win for GOP

At issue is the mid-term redrawing of New York's 11th congressional district, including Staten Island and a small part of Brooklyn.

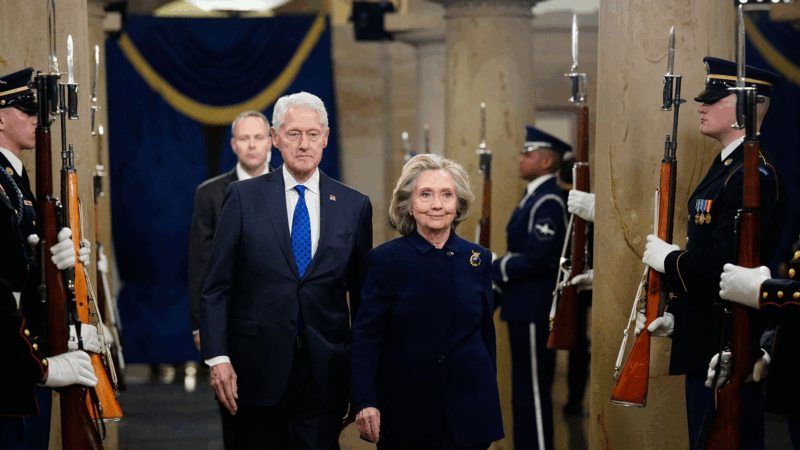

Video of Clinton depositions in Epstein investigation released by House Republicans

Over hours of testimony, the Clintons both denied knowledge of Epstein's crimes prior to his pleading guilty in 2008 to state charges in Florida for soliciting prostitution from an underage girl.

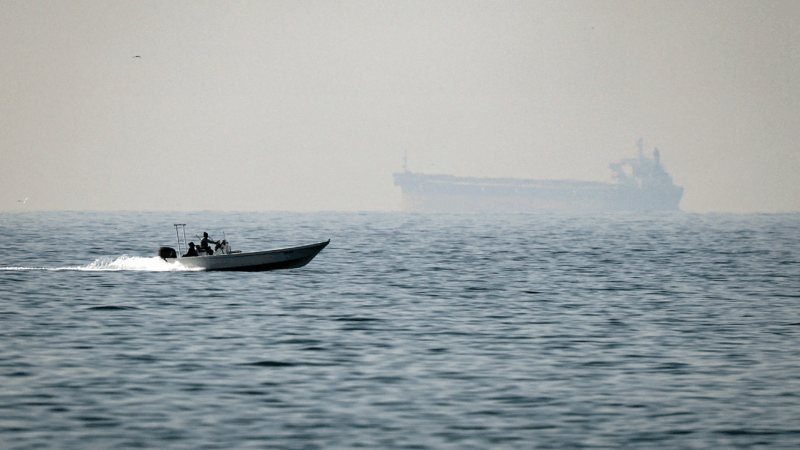

Some Middle East flights resume, but thousands of travelers are still stranded by war

Limited flights out of the Middle East resumed on Monday. But hundreds of thousands of travelers are still stranded in the region after attacks on Iran by the U.S. and Israel.

Oil prices surge, but no panic yet, as Iran war continues

Global oil prices are in the high $70s as traffic through Strait of Hormuz comes to a halt. Some analysts have warned they could top $100 a barrel if the stoppage is prolonged.