A train rumbles through the sunset in Birmingham’s Railroad Park. People are out jogging and riding their bikes, and drivers at the edge of the urban green space bump music and playfully rev their engines as they pass by.

Seated on a bench, Darrell Forte — who leads an annual Black men’s summit to discuss improving the city — describes work he’s done with young people. They’ve shared something with him that belies the tranquil scene.

“‘I want this song to be played, I want this to be worn at my funeral,'” he said, recounting those conversations. “You’re 14, 15 years old, rationalizing that you probably won’t live to see 22, 23. That’s shocking.”

This year, gun violence has rattled the Magic City. While a deadly mass shooting in the city’s busy Five Points South area captured national attention, it only added to a year in which the city has been edging steadily closer to its homicide record.

Members of Black men’s groups in the city said they’re meditating on ways to address the spike. They want to address a sense of fatalism and lack of opportunity they find in some young men, that some say is tied to violence.

“Because you’re just like,’ ‘I’m going to end up like one of them anyway, I’m going to end up dead anyway, I’m going to end up in jail, anyway,” Forte said. “We rationalize things that we shouldn’t rationalize.”

In majority-Black Birmingham, as with many other Southern cities, young men of color are more likely to be felled by gunfire. At least 70 Black men under the age of 40 have been killed in Birmingham this year alone, coroner’s data show.

Communities of color are also more likely to be affected by gun violence largely “because of structural racism,” said Silvia Villarreal in a previous interview, noting Black children’s and teens’ homicide death rate that she said is 18 times that of white children.

“I don’t know how it’s not on the front page of the news,” said Villarreal, director of research translation for the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health’s Center for Gun Violence Solutions.

Forte said young men from some parts of the city are struggling with something like PTSD or “shell shock,” their lives walled in by barriers: addiction, incarceration, hunger and death.

In the wake of this year’s shootings, he convened an emergency Black men’s Zoom meetup this fall to encourage people to air frustrations and talk about how they can help. He also gets people together monthly to discuss things like financial and mental health.

“I think a lot of men, we’re so busy trying to conquer and trying to make money and trying to succeed and trying to get out, if you are from certain neighborhoods, and ‘never go back’ — that’s the no. 1 thing I hear,” he said.

“But we can’t do that.”

Breaking the cycle will take ‘much more than just policing’

Nationally, homicide is ebbing from a pandemic-era crest.

Analysts celebrated a projected murder decline of more than 10% across the country earlier this fall. In the South, cities such as New Orleans have enjoyed dramatically declining murder rates.

But that makes regional hotspots more perplexing for some communities. Baton Rouge homicides are trending upward, and Birmingham has seen tragic events such as two shootings on one July day in which a total of seven people died, including a five-year-old Black boy.

The deaths have stirred angst among city leadership, especially Mayor Randall Woodfin, who has spoken out in frustration about the violence and called for stronger gun-control rules.

Woodfin has lost family members to gun violence, reports say.

“Right now my mind is on the families who are experiencing a sudden, giant void in their lives,” he wrote on Facebook following the Five Points South mass shooting. “The children who are experiencing loss and grief far, far too soon.”

Chris Anderson, a Talladega College police chief, retired Birmingham homicide detective and former reality TV personality, said he’s seeing something different with this year’s gun violence in Birmingham. Lesser crimes like burglary aren’t rising in tandem with the homicides affecting young men.

To him, that means there is an answer to what’s happening, and new approaches are needed.

“It’s going to take much more than just policing,” Anderson said. “It is going to take a connection between the community and police and our business partners and a lot of the people that can come in and offer some outside help.”

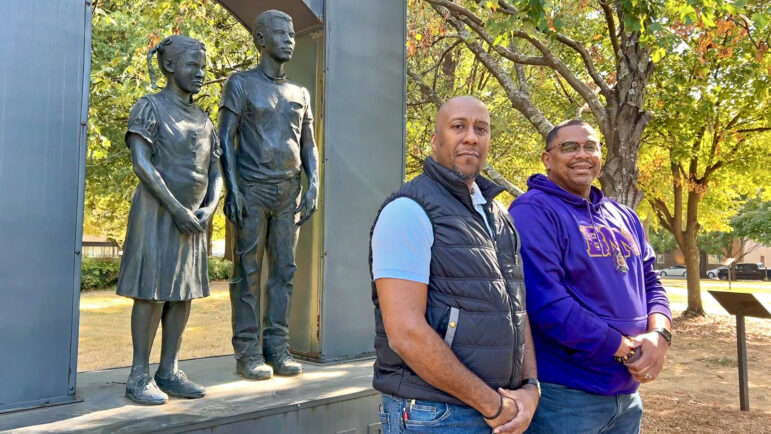

Anderson and a friend, Lamar Lawrence, are involved with 100 Black Men of Metro Birmingham, which mentors young men — mostly of color — through college age. The group is a local chapter of a national, civic-minded organization.

Lawrence and Anderson said their members have found that young men’s lives are steeped in social media videos that sometimes glorify violence. Most of them, they believe, just long to be part of something bigger than themselves.

“That’s why gangs are so successful. They’re like families,” Lawrence explained.

Mentoring can “break the cycle of crime before it even begins,” Anderson said. The group hopes to demonstrate alternative pathways for younger people, giving them options beyond what’s outside their front door.

For now, chapter members will be thinking and praying about how they can help with the violence affecting young men in their city.

“I’m a Black male, but we can kind of become numb, or this compassion fatigue can kind of set in,” Lawrence said. “I think that’s the thing that we have to fight against.”

No easy fix

Alongside community members, the city of Birmingham is making its own efforts to curb the gun violence that has slain younger men.

Anderson was recently appointed to a new commission that will study homicide in the city. Other initiatives include a re-entry program for kids getting out of jail. A new interim police chief also has been sworn in to take over since the agency’s previous chief, Scott Thurmond, announced his retirement in October.

Jeffrey Walker, a University of Alabama at Birmingham criminal justice professor, said the root causes of and solutions to violence are complex, with “no Band-Aid big enough to fix this.”

Walker helps manage a shootings database he said has even predicted some area shootings by tracking social media interactions and social relationships. He said Birmingham is dealing with so-called “immature” gangs, marked by posturing and retaliatory gun violence.

But police response, on its own, is generally not enough to address spikes in violence, he said, and even mentoring programs might not be a complete fix. Of the latter, he supports them, but said they alone “really struggle to stop the cycle of violence in neighborhoods.”

In his view, the issues that lead to gun violence are often the result of decades of decision-making, such as hollowed-out public schools and a lack of quality jobs close to where people live.

“You have to change the economic viability of people in the neighborhoods,” he said. “They have to not be thinking that this is all I’ve got and I’m never going to make it.”

Shopping for mouthwash at a dollar store in Birmingham’s Ensley neighborhood, W. Taft Harris Jr., the pastor of an LGBTQ-friendly church group, said more attention has come to gun violence with increased gentrification in the city that’s pushed more people of color to the margins. For that reason, he has some skepticism about responses to it.

Taft has two Black sons in their 20s and says he’s put a lot into reminding them to be conscious of how they’re perceived by their community. That includes minimizing risk during interactions with law enforcement following the killings of many Black people by police.

But he has also been touched by violence, as a friend was murdered as a bystander during a recent gas station shooting in Birmingham. He said deaths of Black men — whether by gunfire or at the hands of police — affect them all.

“I found myself crying over young men that I have never met,” he said.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.