A new school year is underway for high schoolers in the Gulf South, and with it comes pep rallies and fall sports — specifically football.

High school football is a big deal down South. Teams spend their summer lifting weights, running up and down stadiums for conditioning and studying playbooks. Many young student-athletes dream of leaving lasting marks in their communities and shining under the Friday night lights.

The last thing they are thinking about is how hot it is outside.

“I know [if] we could play through the heat in the summer, then we could play through the heat in the game and… we would be more prepared for the game,” said Joel Ray, a junior linebacker at P.D. Jackson-Olin High School in Birmingham, Alabama.”I tell myself that [I] just go out and get better, no matter what the condition is.”

But while athletes like Ray aren’t too concerned with the extreme heat of the summer, the adults in his life are, including their parents, coaches and training staff.

Sports and health experts emphasize the importance of athletic trainers being on the field at all times to prevent the worst from happening.

In 2020, Remy Hidalgo, a 16-year-old high school junior, collapsed during football practice and later died from an apparent heatstroke in Denham Springs, Louisiana.

On Aug. 13 in New Brockton, Alabama, Semaj Wilkins, a 14-year-old freshman at New Brockton High School, also collapsed at practice. After receiving CPR on the scene, he later died in the hospital. His cause of death is still unknown.

Krishanna Leonard, the head athletic trainer and a health science teacher at A.H. Parker High School in Birmingham, said incidents like Hidalgo’s and Wilkins’ are her worst nightmare.

“One of my students asked me the other day what was or what is something that they don’t want to happen injury-wise. And I told them it was an injury that I can’t fix… someone passing away,” Leonard said.

Planning ahead

Football is the leading sport in the United States for exertional heat stroke deaths, according to Douglas Casa, a kinesiologist and CEO of the Korey Stringer Institute — a non-profit housed at the University of Connecticut’s College of Agriculture, Health and Natural Resources dedicated to preventing sports-related deaths.

More than 90% of all heat stroke deaths in high school sports, Casa said, are football players, and since 1995, data shows almost all of them have been linemen.

“There’s a really specific risk to offensive and defensive linemen,” Casa said. “We’ve been working really hard to try to change how conditioning sessions happen for [them] because they can’t be expected to do the same kind of things that safeties or cornerbacks or running backs are doing. They have to have different expectations.”

But heatstroke deaths typically don’t happen in games, Casa said, but in long workouts and conditioning sessions. That’s why, before the season started, Leonard met with Parker’s team physician and coaches to make a plan on how to keep their players safe, specifically when dealing with heat and heat-related illnesses.

Casa recommends four modifications for high school football programs when dealing with heat exhaustion:

- a work-to-rest ratio based on the conditions of the day

- acclimating players to the heat by phasing in various levels of practice over the first couple of weeks

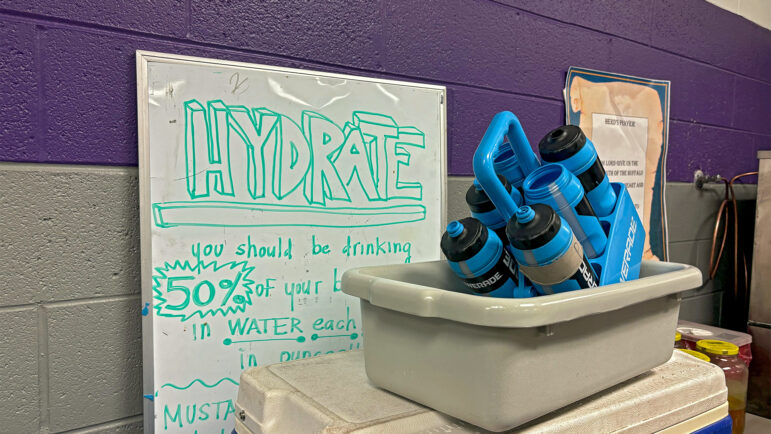

- keeping players better hydrated by having more water breaks and having water nearby for informal breaks

- having different expectations for players who play different positions

Leonard said Parker’s football program has already implemented some of these modifications, and the coaching staff also changed summer practice times — moving them to the early morning instead of the afternoon.

Heat exhaustion can easily go undetected, so Leonard said she looks for signs and symptoms, like if a player is not visibly sweating or sweating excessively, constantly.

Parker’s roster has players who are being recruited by high-profile universities, so many players may have extra workouts before or after their team’s scheduled workout. Leonard said she makes sure to educate the athletes on the importance of both nutrition and hydration.

“Sometimes when we think about heat-related illnesses, we only think about what they’re consuming as far as Gatorade and water,” Leonard said. “We don’t think about what they’re consuming as far as food.”

This year, Parker and six other Birmingham City Schools also have a new weapon in their Emergency Action Plans to help treat heat exhaustion — cooling vests. If a player has a heat stroke, Leonard said the single-use vests can regulate an athlete’s core body temperature before they are taken somewhere else for further care.

Leonard said the vests, donated by the University of Alabama at Birmingham, are crucial because failure to regulate the body’s core temperature before other treatments — like ice baths — can lead to organ failure.

“Hopefully, we don’t have to use it,” Leonard said. “But we have it, and it’s better to have it and not need it than not have and need it.”

Student athletic trainers play ‘very vital’ role

Along with her work as Parker’s athletic trainer, Leonard also leads the school’s sports medicine program. There, a handful of students assist her with helping injured players and keeping them hydrated.

“Some people think of them as just water girls or water boys, but they actually provide much more than that,” Leonard said. “Their role is very vital.”

Kennadi Pettaway, a senior in the sports medicine program, said she wants to pursue a career in health care after high school, inspired by Leonard and her older sister who was also in Parker’s sports medicine program.

“We tape ankles and wrap hands, or just put on Band-Aids. It could be simple sometimes,” Pettaway said.

Coaches set the standard

As prepared as Parker is for the season, not every school is fortunate enough to have a sports medicine program with a mock hospital in the back of the classroom or $800 cooling vests.

According to Casa, a third of U.S. high schools don’t even have an athletic trainer on staff

“That would scare the crap out of me if I’m a parent,” Casa said. “And my kid is doing a few hours’ practice and they’re in harm’s way, and their coach is going to decide if their children live or die from a heatstroke or a cardiac event, or a head injury.”

When it comes to shifting players’ attitudes about heat precautions, Casa said that coaches ultimately need to set the standard — encouraging them to say if they are not feeling well or need a break.

“Would an athlete speak up if they’re not feeling well? A lot of times, they won’t,” he said. “They don’t want to appear weak. Maybe they’re fighting for a starting position or they’re trying to make varsity instead of JV. The coach creates that culture where they let the athletes know, yes, we’re going to try to win a state championship. But most important, above all else, is your health and safety.”

Along with the four modifications, Casa also has another suggestion for high school football programs, one he predicts will happen within the next two decades as temperatures continue to increase — switching the season from the fall to the spring.

“I think, eventually, we’re going to have to move high school football to a spring sport, just because of how it’s getting hotter and hotter over time,” Casa said. “I honestly think it’ll be almost a requirement.”

Gulf States Newsroom Health Equity Reporter Drew Hawkins contributed to this report.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.