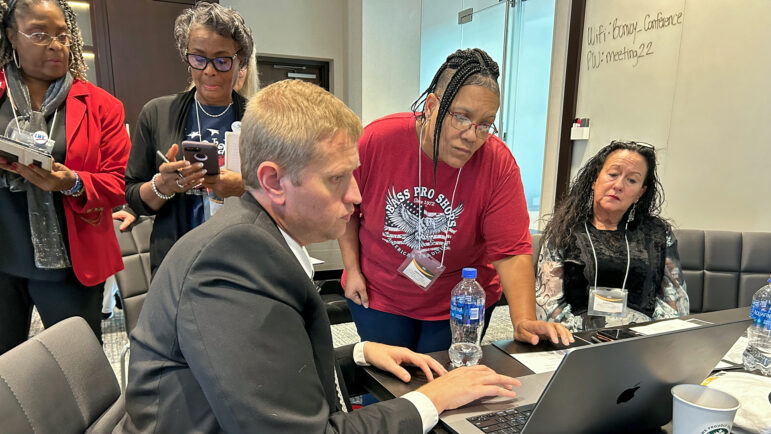

In a drab hotel meeting room just outside of Jackson, Sabrina Butler-Smith, a woman who once sat on Mississippi’s death row, peered over a laptop with former state legislator Roun McNeal.

The exoneree asked McNeal how to learn about past bills, but even the former lawmaker expressed puzzlement as he navigated the Mississippi legislature’s website.

The two were taking part in a March legislative advocacy training for formerly incarcerated people and people with loved ones in prison. The inaugural event aimed to teach people affected by the justice system about the art of political influence.

Policymaking often leaves community members anxious to weigh in, but perplexed as they grapple with proposed laws, said Cynetra Freeman, the program’s organizer and executive director of the Mississippi Center for Reentry.

“It’s like, one minute they’re simplistic, and then they become very complex. And it’s like, wait, how do we go from elementary, to over here, to law school?” said Freeman. “So then I have to reach out to somebody: what does this mean?”

Freeman put this training program together out of a personal desire to decipher legislation, especially bills that affect previously incarcerated people like her. Before founding the Mississippi Center for Reentry, Freeman said she served a three-year sentence for drug trafficking.

Her biggest challenge now, she says, is “reading those doggone bills.”

The programming comes as criminal justice bills churn through Gulf South statehouses. In neighboring Louisiana, a recent whirlwind special session on crime produced new laws dealing with the prosecution of 17-year-olds, the death penalty, parole and more.

Alabama lawmakers have taken up death penalty and indigent defense bills, while Mississippi has considered changes to parole, juvenile sentencing and other practices, many of which died at the committee stage.

A path to political participation

The in-person seminar in Ridgeland, Mississippi, followed online training sessions, at which participants learned more about storytelling basics and Capitol etiquette, Freeman said. It preceded a group trip to the statehouse to put new skills into action.

Such training also suggests a path to political participation beyond the ballot box for Mississippians with criminal records. Mississippi’s voting rights laws for people with some convictions are among the nation’s most restrictive, experts say. That’s provoked court challenges.

Peg Ciraldo, co-president of the League of Women Voters of Mississippi, called the group’s statehouse visit and lobby efforts “so worthwhile,” while criticizing the state’s voting limitations.

“There might be people who made a mistake, who want to vote, who have a really good head on their shoulders — and we want them voting,” Ciraldo said.

At the training, a small group of attendees — joined for the session by a few like-minded advocates — bonded as they fretted aloud about health emergencies for incarcerated loved ones and Justice Department findings about unconstitutional conditions at Mississippi prisons.

Butler-Smith, who said she was incarcerated for more than six years and who now lives in Memphis, was eager to learn about the lawmaking process — for example, what happens after a law is written, and how it can change.

“But I would also want to know … the hardest thing, which is how to get in their hearts,” she said of lawmakers. “How to turn them.”

Butler-Smith spoke of enduring bleak prison conditions for years and challenges finding work and housing when she was released. She is interested in helping people with similar difficulties.

Participants hung on lobbyist LaDarion Ammons‘ words as he recapped the details of bills they might be interested in, including attempts to expunge some criminal records automatically.

He offered insight on some bills’ authors and shared pro-tips on how best to recognize lawmakers — by signature pins often worn by House and Senate members — and warned attendees to try to keep their stories succinct.

“Use that elevator pitch,” Ammons said, snapping his fingers.

Former state representative Kathy Sykes, who said her son is currently incarcerated, helped lead role-playing exercises, acting the part of a checked-out lawmaker who griped about a bill’s lengthy page count.

“Anybody can be a lobbyist. Anyone and everyone,” she said. “You just have to have the desire and the passion to do it.”

Despite the lighthearted tone, participant Elizabeth English’s hands trembled as she sat across from Sykes to practice pushing for bills.

English was attending the training, in part, to speak against Mississippi’s habitual offender laws. She said those rules led to a 10-year sentence for her son over a drug case, an outcome which has devastated her family.

English’s voice quivered with emotion in an interview, explaining the high cost of her son’s imprisonment.

“He was not even allowed to attend his child’s funeral, to touch him or to even see him one last time. So that was a harsh punishment, in and of itself,” she said.

The prior year, English had visited the statehouse, but had not spoken up much, she said. With what she describes as a “G.E.D. and a G-O-D” education, she’s had a lot of questions while trying to engage with legislative language.

‘We have to keep trying’

The next morning, group members reconvened at the state Capitol in Jackson, which thrummed with energy. Hallways teemed with members, legislative staff and people from various advocacy groups. Dour portraits of past officials gazed down from the walls.

Throughout the day, the group visited legislative chambers and a committee hearing, with some bumps in the road on the way. Bills they hoped to hear didn’t immediately crop up in a committee discussion, and it was challenging to recognize representatives in the crowds.

More success came in the afternoon when the group gathered around a table draped with a flag that read “formerly incarcerated caucus.” Several lawmakers and advocates stopped by, and Butler-Smith started telling them her story.

She jested with House Appropriations A committee chairman John Read and mixed with members who hailed from Hinds County, Gulfport and beyond. One lawmaker compared the story of her exoneration to the plot of a legal thriller.

A stack of educational handouts about bills the group highlighted as important dwindled until it was gone. Butler-Smith later said she found the lawmakers “receptive.”

“If you can get people to just listen for a fraction of a second, I feel like you can tug a little way, some kind of way at their heart, just a little bit,” she said.

After the event, English emailed to say a bill she’d been hopeful about — which would’ve automatically expunged some criminal records — failed.

“We have to keep trying,” she wrote.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.