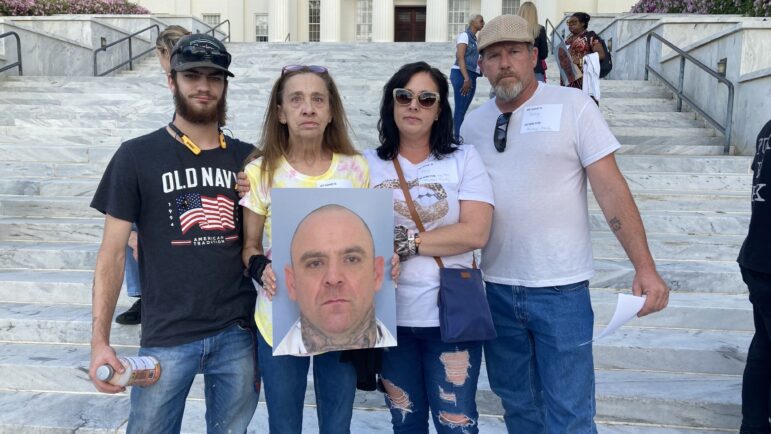

At the base of the steps leading to the Alabama Capitol, volunteers stand behind a fold-up table, greeting dozens of families and distributing large printed photos of their loved ones.

The 266 images are headshots of people who died inside Alabama’s prisons in 2022, the deadliest year on record.

Most of the pictures feature men with shaved heads, wearing prison uniforms.

“When I was preparing for this event yesterday and just saw the volume of faces, it really is so emotional,” said Lauren Faraino, director of the Woods Foundation.

Faraino’s group organized the event on Tuesday afternoon, around the same time state lawmakers gathered at the capitol for Gov. Kay Ivey’s State of the State speech.

“We are here today to tell them a prison sentence should never be a death sentence,” Faraino said.

In addition to hundreds of deaths last year, dozens of incarcerated people have died so far in 2023. The deaths have been linked to illness, violence, drug overdose and suicide.

“We found out about my son’s death, an inmate called us and told us. The facility never did call us,” said Eddie Richmond Jr., who attended the vigil with his family.

Richmond’s son, Eddie Richmond III, was 20 years old, serving a three-year sentence at Fountain Correctional Facility. He died last December, after serving less than a year in prison.

Richmond is still waiting on results from an autopsy, but he suspects that his son died from a drug overdose.

Many families learn about their loved ones’ deaths through other incarcerated people, sometimes via Facebook posts. They often struggle to get additional details from prison officials.

For weeks, Krislyn Allison has been trying to find out what happened to her cousin Adrain Kimbrough, who died this January at Limestone Correctional Facility after being assaulted by another incarcerated man.

Allison said when her family requested Kimbrough’s body, a prison official discouraged it.

“He said ‘Ma’am are you sure you want this body?’ I said, ‘This body? He’s a person. Yes we want his body,’” Allison said. “So we got the body. The condition that it was in, it was so horrible, she hadn’t let anybody see it.”

According to the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), Alabama’s prisons for men are among the deadliest in the nation. The DOJ is suing the state to try to force change, citing rampant violence in the prisons, chronic overcrowding and a dire shortage of correctional officers.

In 2021, Alabama lawmakers approved a $1.3 billion plan to build two new mega prisons for men.

Many people attending the vigil said that’s not going to fix the issue.

“Buildings did not kill these people,” Lauren Faraino announced to the crowd. “We don’t need new buildings. We don’t need to give more money to a corrupt and failing agency. We need a new culture. We need accountability. We need answers. We need better leaders.”

Holding up the photos of their loved ones, families filled the capitol steps just hours before Gov. Ivey delivered her State of the State speech to a room full of state lawmakers.

Later that evening, inside the state capitol, the tone was noticeably different.

Gov. Ivey didn’t discuss prisons during her speech, aside from mentioning a salary increase for state correctional officers. She also advocated for a new bill to increase criminal penalties for people convicted of distributing fentanyl, a powerful opioid linked to most overdose deaths.

“By doing this, we will put any traffickers of this deadly drug behind bars and keep them there,” Ivey announced as the crowd applauded.

Illicit drug use was also a key topic among people attending the vigil. Many families said they want officials to keep the deadly substances out of state prisons and prioritize treatment.

Darlene Halks suspects that fentanyl was involved in the death of her 40-year-old son Michael Hardy, who died at Ventress Correctional Facility in November 2022.

“The prisoners deserve more than what they’re getting,” Halks said. “They are human. They’re not pieces of garbage.”

As the vigil continued, the group joined together to sing “Keep Your Eyes on the Prize,” before walking to the historic Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church, where they lit candles and continued to share stories of loss and resilience.