To read and listen to this story in Spanish, click here.

On a cold evening just before Thanksgiving, about two dozen families gathered at an event space near Birmingham, Ala.

The room was buzzing with anticipation. Volunteers in blue T-shirts prepared a buffet with pozole, salads, gorditas and cakes, while men and women decorated tables with balloons and flowers.

They were excited and nervous, waiting to reunite with their parents for the first time in decades.

“It’s very emotional,” María del Rocío Rodriguez Tellez said.

Rodriguez last saw her mom in 1997, right before leaving her hometown in Michoacán, Mexico.

She immigrated to Alabama with her husband and son, looking to find work and earn a more stable income. But she didn’t realize she would never return to Mexico, and her parents would not be able to visit her in the U.S. until 25 years later.

“You know the desire to come here, for a better future. But you sacrifice a lot,” Rodriguez said.

Like most people in the group, Rodriguez’s family has remained separated by border restrictions and visa denials.

Until recently, Rodriguez was undocumented, meaning if she visited family in Mexico, she would risk not being able to get back into the United States. And even now, with a work permit and a pending immigration case, Rodriguez still doesn’t have permission to leave and re-enter the U.S.

Her mom, Elitania Tellez Maldonado, tried to visit Rodriguez over the years, but said her applications for a tourist visa from Mexico were denied three times.

“I don’t know why,” Tellez said. “I cried a lot because they didn’t give it [the visa] to me. I felt very frustrated.”

It’s a situation many immigrants encounter

Many families experience similar roadblocks, according to Monica Black, communications coordinator with the Alabama Coalition for Immigrant Justice (ACIJ), the group organizing the event.

“There are people who have applied seven times and have been denied,” Black said.

To get a tourist visa to enter the United States, Mexican citizens have to show ties to Mexico, such as proof of employment or a mortgage, to convince U.S. immigration authorities that they plan to return home after their trip. They also have to show that they have sufficient money to cover the estimated costs of travel.

Black said their program, Abrazando Nuestras Raíces, or Embracing Our Roots, helps streamline the process and leads to higher visa approval rates, because parents apply together as part of a group cultural visit.

The program is open to Mexican parents age 60 and older who haven’t seen their children living in the U.S. for at least 10 years. Participants must pay for all application fees and, if visas are approved, travel costs.

ACIJ staff work with Mexican officials to assist parents with paperwork and prepare them for interviews.

But the process can still take a while.

Depending on where they apply, Mexican citizens have to wait up to two years or more to interview for an individual tourist visa, according to the U.S. State Department website.

Rodriguez’s parents waited even longer.

They started the application process with Abrazando Nuestras Raíces in 2019, before the pandemic added an unexpected years-long delay.

When their visas were finally approved in June 2022, the couple joined about two dozen other parents to plan a long-anticipated trip to Alabama.

In mid-November, 73-year-old Tellez and her husband, 75-year-old Camilo Rodriguez Mares, arranged for a shuttle bus to drive them five hours from their small town in Zacapu, Michoacán, to the Mexico City airport.

The couple boarded a plane for the first time in their lives, flew to the Atlanta airport and boarded a bus to Birmingham.

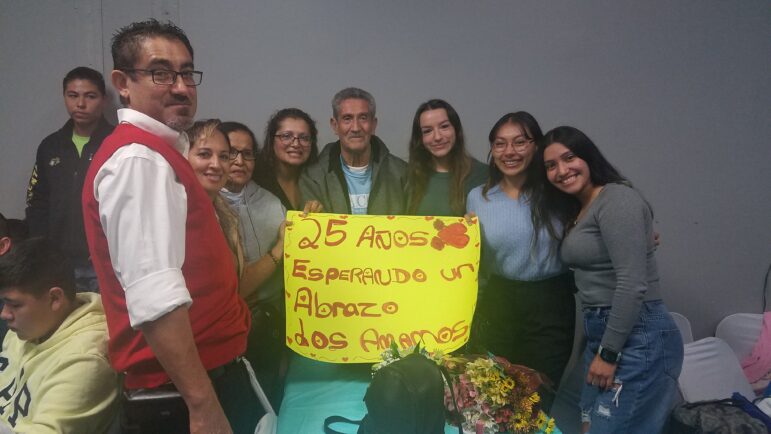

Hours later, they arrived at the event space in a suburban shopping plaza, tired but happy, erupting in group cheers of “Si se pudo!” – a well-known phrase meaning “Yes, we could!”

One by one, volunteers escorted the parents off the bus and into the decorated room, where they reunited with their children amid emotional applause, tears and hugs.

The celebration lasted hours, with food, music, dancing and speeches.

“The result of this program is crossing borders that have sadly divided us for many decades, and doing it the way families deserve,” Natividad Gonzalez, ACIJ’s community organizing consultant, told the crowd. “Our families deserve to have this opportunity, but not all of them have it.”

Parents visiting this year are part of the second group that’s come through the Abrazando Nuestras Raíces program, which started in 2018.

ACIJ officials are trying to organize more visits, and have been spreading the word through social media posts and information sessions throughout Alabama.

It’s led to an overwhelming amount of demand.

As of mid-December, nearly 200 parents are waiting on visa interviews in Mexico, 400 parents are registered to start the visa application process in 2023 and at least 600 more families are on a waitlist to learn more and apply.

“It’s a job that is very satisfactory for us, and for all the families,” Black said. “And we see that it’s a need that our community is asking for.”

Many Mexican immigrants have lived in Alabama for decades, and have raised their kids and grandkids in the state. Black said they want to share that life with their parents.

The visits last one to two months, and families stay together, soaking up every minute together.

“It’s something I carry deep in my heart, to see my children, to share life with them, to get to know so much of their lives here,” Tellez said.

“And to get to know all the great-grandchildren. It’s wonderful.” Mares added.

Since reuniting in November, the Rodriguez Tellez family has gone to the beach along Alabama’s Gulf Coast. They attended a minor league basketball game featuring the Birmingham Squadron vs. the Mexico City Capitanes. They’ve enjoyed preparing family meals and staying up late watching telenovelas on TV.

And they can’t wait to celebrate Christmas together — for the first time in a quarter century.