Chants of “No justice, no peace” and “I can’t breathe” filled the air in Kelly Ingram Park in Birmingham, Ala., on May 25, 2021, one year after a police officer killed George Floyd. It’s the same space where activists gathered this time last year.

“I was in the exact same place fighting for George Floyd’s justice,” said Satura Dudley, 21, executive director of the social justice group Cell A65. “Obviously the trial happened. We allegedly got justice. That’s not really justice when he’s already dead.”

Floyd’s death, after nine minutes under the knee of a police officer, is what inspired Dudley, 21, to become an activist.

“Last year, I really was just coming to a protest to come to a protest,” said Dudley. “And now I’m helping lead a movement.”

This event is one of a handful of vigils and marches held across Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana this week. But in the birthplace of the civil rights movement, there hasn’t been as much action as in other parts of the country in the year since Floyd’s death.

A protest in downtown Jackson, Miss., last summer brought thousands out to march from the governor’s mansion to city hall calling for change. A year later, after former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin was found guilty of murder, a lot of work is happening behind the scenes. But in Jackson, and many other areas in the region, the streets are quiet.

A Call To Action

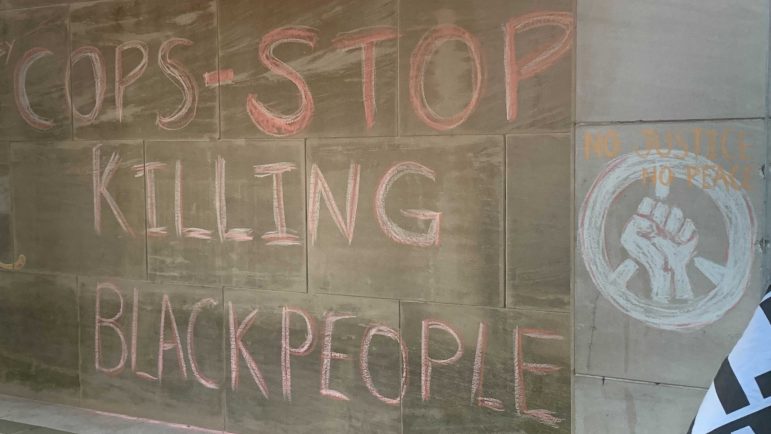

George Floyd’s murder was a moment of reckoning that propelled a lot of young people in the South to rally for racial justice.

“For a lot of other people of color and a lot of white people, the George Floyd case was kind of like that defining moment for their understanding of police brutality and a better understanding of the Black experience in America,” said Maisie Brown, 19, lead organizer of the Black Lives Matter protest in Jackson in 2020.

Kobee Vance,Mississippi Public Radio

Thousands of protestors march through downtown Jackson, Miss., in June 2020 after the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

A survey out this week from the nonprofit group E Pluribus Unum finds that Southerners – regardless of their race – have overwhelming support for major police reforms. The 1,200-person survey found some differences across racial and political lines, but a majority of respondents don’t think lawmakers have done enough since George Floyd’s murder.

President Joe Biden had set a deadline of May 25 for the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, which contains reforms such as a ban on chokeholds. It passed the House of Representatives in March but is stalled in the Senate. Floyd’s family is urging legislators to pass legislation they believe will protect Black men and women.

Some activists point to the removal of Confederate symbols across the region and Alabama’s law permitting medical marijuana as signs of progress.

But Brown said she wants to see a lot more.

“I don’t think that there has been nearly as much aggressive police reform as there should be right now,” Brown said. “So I think justice looks like us not having more George Floyds.”

Beyond George Floyd

Mississippi has its own case of a Black man dying after an officer kneeled on him. Robert Loggins died while in custody at Mississippi’s Grenada County Jail in 2018. The state initially called the death an accident. Calls for an investigation came after the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting obtained video from inside the jail appearing to show an officer putting his knee across Loggins’ neck or head.

“These in-custody deaths have come to represent something of a stain in the fabric of this country that we love and hold dear and so this family wants to help blot that out, specifically for justice for Robert Loggins,” said Jacob Jordan, the attorney representing Loggins’ family.

In neighboring Louisiana, another family is fighting for justice for Ronald Greene. He died after a police chase in 2019. White troopers initially blamed his death on the impact of a crash. Graphic bodycam footage obtained by the Associated Press last month, shows officers repeatedly using stun guns on Greene, punching him and dragging him by his ankle shackles.

Decades ago, civil rights activist Hezekiah Watkins, who was a Freedom Rider during the 1960s, was arrested more than one hundred times.

“Each time I was arrested, I was afraid because you never can tell when you left going to a situation whether you would return,” said Watkins. “That fear, it’s still there.”

Now he works at the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, where his own mug shot hangs on the wall.

Ashley Norwood,Mississippi Public Broadcasting

Hezekiah Watkins, a civil rights activist and Freedom Rider, points to his mugshot in the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum. He was 13-years-old when he was arrested and taken to Parchman Penitentiary.

Watkins has been involved in the fight for justice since the age of 13. Young people have always been part of the movement for racial justice, but he wants to see more from today’s youth.

“I applaud their effort, but I’m concerned about them because, in my opinion, they are not visible enough,” said Watkins. “There’s a lot of things that’s happened since George Floyd. Where are they?”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Birmingham, Alabama, WWNO in New Orleans and NPR.