While COVID-19 cases continue to devastate the Gulf South and hospitalizations rise, the region’s HIV/AIDS epidemic raged on in the background. Cities like New Orleans and Jackson, Mississippi already had the highest rates of HIV/AIDS in the country, according to 2018 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data. During the pandemic, tests to screen for new infections have plummeted and health experts worry that the HIV/AIDS crisis will only get worse.

Data acquired from the Louisiana Department of Health and the Alabama Department of Public Health show that the average number of screenings for new HIV infections went down significantly between 2019 and 2020.

Alabama’s number of HIV tests administered monthly has been on the decline since 2017, but between 2019 and 2020 there was a steep 25% decrease. Louisiana’s average monthly tests were relatively flat prior to 2019 before seeing a 33% decrease between 2019 and 2020. The Mississippi Department of Health said it does not track all diagnostic HIV tests performed in the state.

The decrease in testing is especially concerning since half of all new cases in 2018 were just in the South and the majority are within the Black community. And while death rates have declined since 2012, the South still accounted for nearly half of the 15,807 HIV-positive people who died in 2016.

Why Resources Shifted Away From HIV Testing

Data about HIV case rates lag a few years, but the steep decline in diagnostic testing does not bode well for the HIV/AIDS crisis.

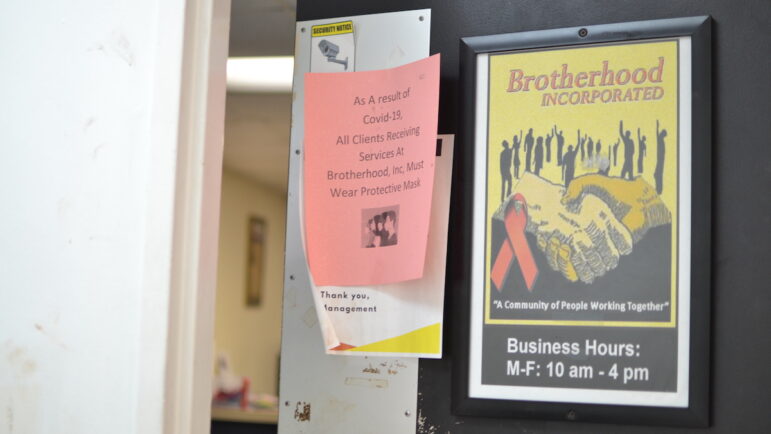

“I would wager what we will see in the next couple of years is an increase in the number of persons who have been newly diagnosed as HIV-positive,” said Veronica Magee, the deputy director of Brotherhood, Inc., a community-based organization in New Orleans that offers HIV testing and other medical services.

When the stay-at-home order was put in place in 2020, some healthcare clinics remained open. Most community-based organizations, like Brotherhood, had to shut down their clinical services, meaning many people at high risk for infection were not being reached.

“People have other needs that are more pressing at the moment, and HIV testing is on the back burner,” Magee said.

Individuals weren’t seeking out diagnostic testing in the same way, and states were limited in their outreach. As COVID-19 spread across Louisiana, officials shifted some resources away from the HIV epidemic to focus on the pandemic. The same department that tracks infectious diseases like HIV was suddenly burdened with tracking COVID-19 cases.

“We had some health, education and social marketing campaigns running for HIV awareness and Hepatitis C awareness. We intentionally asked those contractors to roll back the amount of effort we’re putting out there in that marketing campaign,” said Samuel Burgess, director of the sexually transmitted disease and HIV program at the Louisiana Department of Health. “Because what we really needed to communicate as a health department to the public was … what the [COVID-19] mitigation measures are.”

Attention was also diverted at the federal level. In January 2019, the Trump Administration announced a plan to help end the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the U.S. with a special focus on the jurisdictions with the highest rates of cases, including Mississippi. The plan set out a goal to achieve a 75% decrease in new HIV infection by 2025.

But, a new report from the Mississippi Department of Health indicates that “plans to engage the community were altered and delayed by COVID-19.” The report noted that many health care providers pivoted to virtual town halls and emphasized at-home STD testing.

Outreach Resumes, But Tests ‘Still Lagging’

Even before COVID-19, people in the South confronted multiple barriers, such as a lack of health care infrastructure, high rates of poverty, and limited transportation, that limited regular HIV testing. According to the CDC, Medicaid is also one of the main sources of coverage for HIV-positive people, but Mississippi and Alabama have not expanded coverage.

“The social determinants of health that make a person susceptible to HIV are the same social determinants of health that make a person more likely to come down with COVID-19,” Magee said.

Brotherhood, Inc. was able to open up late last year, but the pace of HIV screenings is still lagging, Magee said.

“We’re beginning to see a trickle of people coming back into the offices for testing,” Magee said. “But that is all very slow because there are so many other things that are the focus — crime, unemployment.”

Shalina Chatlani,Gulf States Newsroom

Veronica Magee is the Deputy Director of Brotherhood, Inc., a community-based organization in New Orleans that offers HIV testing and other medical services.

As Louisiana has opened back up, the department of health has been able to resume some of its original campaigns and outreach efforts. The focus now, Burgess said, is to “band together” across the different types of service providers and community organizations to stem the spread of HIV.

“Gay and bisexual men of color or transgender women — those continue to be some of our highest priority populations in terms of getting prevention services out and engaging with them,” Burgess said. “Certainly Black women also continue to bear a disproportionate share of HIV diagnoses.”

Ramping Up Preventative Health Care Measures

Even without COVID-19 as a factor, there are many cultural issues that prevent people from getting tested. Christopher Roby, a sociologist with the Community Health Center Association of Mississippi, says to remove the stigma around HIV, health care providers have to emphasize and educate people about preventative health care in every possible setting — the same way they would promote the COVID-19 vaccine and mask-wearing.

“Students are coming back to the college campuses and there are community groups that are functioning,” Roby said. “Our goal is to partner with all of these organizations and people to ensure that we get the message out about HIV screenings.”

Roby also wants to see HIV screenings become a routine part of primary care doctor visits.

“When you offer it to every patient that walks through that door, it doesn’t seem like you’re singling out a particular population based on their behavior or their gender identity,” he said.

Roby said it is even more important to ramp up these efforts now as the delta variant surges across the South and could potentially put people back into their homes if another shutdown were to occur, leading to a further decline in HIV screenings.

“People are fixing to have to go back into their homes as we see the rise in COVID cases,” he said. “They are still meeting people online. They’re still taking risks.”

Editor’s Note: This story has been updated.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Birmingham, Alabama, WWNO in New Orleans and NPR. Support for health equity coverage comes from the Commonwealth Fund.