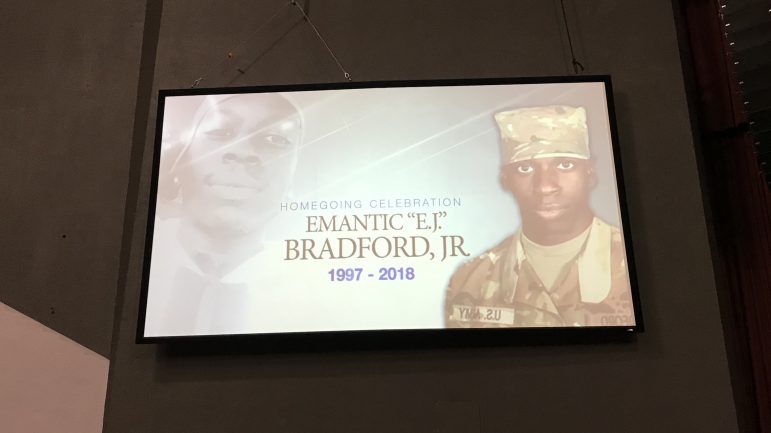

Officials still have not released the name of the police officer who shot and killed a 21-year-old black man Thanksgiving night at the Riverchase Galleria mall in Hoover. A report from the Alabama attorney general’s office Tuesday cleared the officer of any criminal wrongdoing when he shot Emantic “EJ” Bradford Jr. He thought Bradford was the gunman in an active shooter situation.

Hoover Mayor Frank Brocato said at a press conference Tuesday withholding the officer’s identity is about fairness.

“Just as any other private citizen that is investigated and found not to have committed a crime their name is not released,” Brocato says. “That’s the same procedure that we will follow with this officer.”

That’s in line with the position of Attorney General Steve Marshall, who says there’s no value in the public knowing who shot Bradford.

But we do know Officer Darren Wilson shot and killed Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. And Timothy Loehmann was identified as the officer who shot and killed Tamir Rice. Neither of them were criminally charged. Why the difference?

Stephen Rushin, who teaches police accountability at Loyola University Chicago School of Law, says policies vary widely among departments, but it’s not uncommon for police to withhold an officer’s name in situations like this. Rushin says police unions typically push for non-disclosure to protect officers.

Rushin says an officer’s reputation is a concern but there is value in releasing a name because it’s not just about criminal charges.

“Is this the kind of behavior we want officers to be engaged in? Did it violate internal policy? And did the officer receive some sort of punishment in response to the behavior that they engaged in?” Rushin says.

He says without some kind of citizen oversight, you’re basically trusting the police to police themselves.

Kami Chavis, a former assistant US attorney now at Wake Forest University law school, is shocked law enforcement hasn’t released the officer’s name. She says private individuals are not the same as police officers.

“They are empowered to use force and authorized to use force during the normal course of their duties and many times that is appropriate,” Chavis says.

But she says not releasing a name can make police departments look like they’re hiding something which undermines public trust. Chavis adds officer names often come out anyway, for instance, through a civil lawsuit. An attorney for the Bradford family says they plan to file a civil lawsuit.