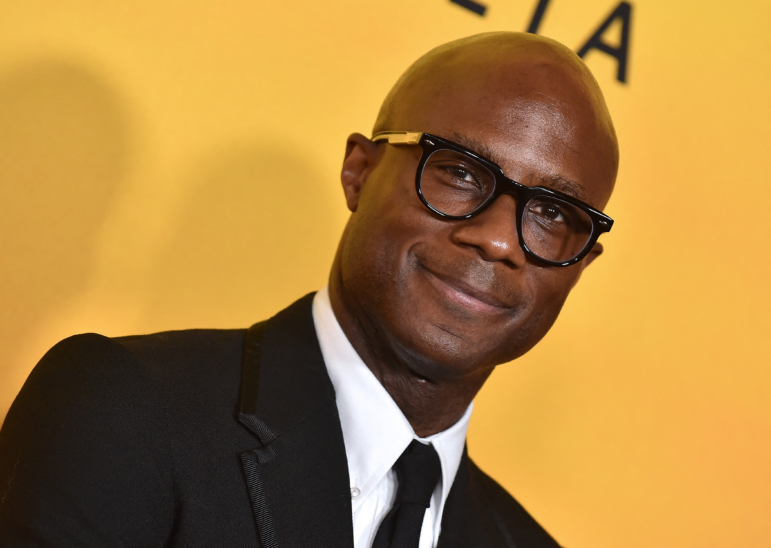

A note from Wild Card host Rachel Martin: It is virtually impossible to watch a Barry Jenkins film and not be emotionally changed. You can’t watch the scene from the Oscar-winning film Moonlight, where Juan teaches Little to swim without seeing the full humanity of both those characters — the fragility and strength and desperation and love all at the same time.

Barry Jenkins never set out to make movies for the masses. He’s a champion of independent film who tells stories about Black life in America — from a film about a one-night stand in San Francisco in the early 2000s to the limited series based on the Colson Whitehead book, The Underground Railroad.

But that’s the thing about art and movies in particular. No matter how specific the experiences reflected on screen, if the story is told as true as it can be — as authentically as possible — the work transcends boundaries. It will mean different things to different people, but it will mean something. And Barry Jenkins has made films that matter in the most profound ways.

So when I tell you that Barry Jenkins is making the newest Disney movie, Mufasa: The Lion King, maybe you need to take a beat because this is the indie filmmaker taking a big swing in the completely opposite direction. But then you remember that Barry Jenkins wants his films to make an emotional imprint on us. And if a little “Hakuna Matata” doesn’t make you feel joy, then I don’t know what will.

This Wild Card interview has been edited for length and clarity. Host Rachel Martin asks guests randomly-selected questions from a deck of cards. Tap play above to listen to the full podcast, or read an excerpt below.

Question 1: Where would you go to feel safe as a kid?

Barry Jenkins: I grew up very poor — in the world that you see dramatized in Moonlight. And I lived in this housing project — I think it was built as barracks, probably for soldiers — and then became public housing.

Martin: This is in Miami, we should say.

Jenkins: This is in Miami, exactly. And in the middle of this complex, there was an old, like, laundromat, like a washhouse. And it was this one-story, maybe like 20-by-10-foot thing, the structure. But it had this flat roof and there was this massive tree above it. And I remember as a child, if things were too heavy or there was too much going on, I would go and I would climb up in the window to get onto the roof and then I would jump onto the tree and I would squirrel up into the very top of this tree — like so high that if someone was walking by, they would never know someone was up there. And I would just go up into this tree and I would just sort of just listen to the sounds of the day. I would just clear my head. And I think I would just stay up there until I felt like I was ready to sort of reenter the world or reenter my life. I haven’t thought of that in a very, very long time because the idea of me climbing trees now is crazy. But yeah, that’s what I would do.

And it’s interesting, later in life I would sometimes go on these long walks as a teenager and I would find these empty houses that had fruit trees in the backyards, you know, it’s Florida, it’s Miami — grapefruit trees, avocado trees. I guess I climb trees a lot. I would climb trees to go feel safe.

Martin: And to get perspective probably. I mean, there’s something about getting high above the din of life and the hard things.

Jenkins: Yeah, it’s weird. There’s a version of it that maybe is: you’re trying to avoid all these different things, but I think solitude can be very fortifying as well. And to sort of recenter yourself before you reenter the rigors, the demands of everyday life, especially that life, because it was a lot for a child to process.

Question 2: What is something you still feel you need to prove to the people you meet?

Jenkins: Because of where I came from and what I do, that there’s just always this version of me that feels like I’m not enough, you know? That I constantly have to prove, to reaffirm my ability, my value, my merits. And so any time I walk onto a set, I walk into a conversation like this — and it sucks because it’s the antithesis to us actually communicating and connecting — is me bringing this voice in the back of my head that feels like, “I am just simply not enough. I’m not good enough.”

The flip side is, you know, it keeps me very driven. I am trying to put my full self, I am trying to just be unimpeachably affirmative, of value, of merit — just of merit. And I think it’s something that will always be with me, unfortunately, because I don’t think it’s something that adds value.

Martin: You haven’t experienced it abating over time?

Jenkins: No, no, no, I have not. I made this film If Beale Street Could Talk, which is an adaptation of James Baldwin. And there’s this great quote that we put into the movie. It’s taken directly from the book: “The children have been told that they weren’t worth s*** and everything around them proved it.”

It’s, on one hand, a very lovely, beautiful book, but also a very angry, justifiably angry, book. And something of that line just stays in the back of my head. And for some reason, I feel like I’ll always be working in the opposite direction to disprove it, you know? That I’m not worth s***. And so that’s it. So I’m going to give you the honest answers, Rachel Martin.

Question 3: Do you think there’s order in the universe or is it all chaos?

Jenkins: I think it’s all chaos. I really do. I have to believe that.

Martin: Woah. People usually give the complete opposite answer — that there is order because they have to believe that — because the alternative is so unsettling.

Jenkins: The alternative is unsettling. But there’s also something quite beautiful about it as well. I do believe that the universe is chaos and our role in it, which is I think the beauty and the agony of life, is to make sense of it and to try to create order, but to do it ethically, to do it in a way that’s spiritually balanced.

I truly and fully believe that, because if the universe was completely the situation of order, I think the history of me, you know, I’m the descendant of African slaves — what order gave birth to that path? That certainly came out of complete chaos and horror. But I think we can take that chaos and create something quite profound. I really do.

I mean, Rachel Martin, it is December 2024. You’re going to tell me the last five years on this planet, you know, have been orderly? They have been beyond chaotic. I mean, beyond. And when we go out and create work — when you do these interviews, when I create these films — I do think we’re all trying to have conversations, dialogue, to make sense of all this chaos, to show that we’re all navigating it in our own ways and we are just doing the best we can.

Martin: Indeed. And I think when people give the opposite answer — that there’s order — it’s their projection of order that makes the chaos manageable. You know?

Jenkins: It is true. I have to be honest and say most of the people who come onto the show — myself included — we’re speaking from places of extreme privilege. Not all of us, but quite a few of us. And I just can’t ever really sit in that place.