DUBAI, United Arab Emirates — Loft-style apartments with floor-to-ceiling windows, an off-shore oil and gas rig, advanced industrial zones and park-lined neighborhoods. This is “New Gaza,” a vision laid out by the Trump administration for the destroyed Palestinian territory after two years of war.

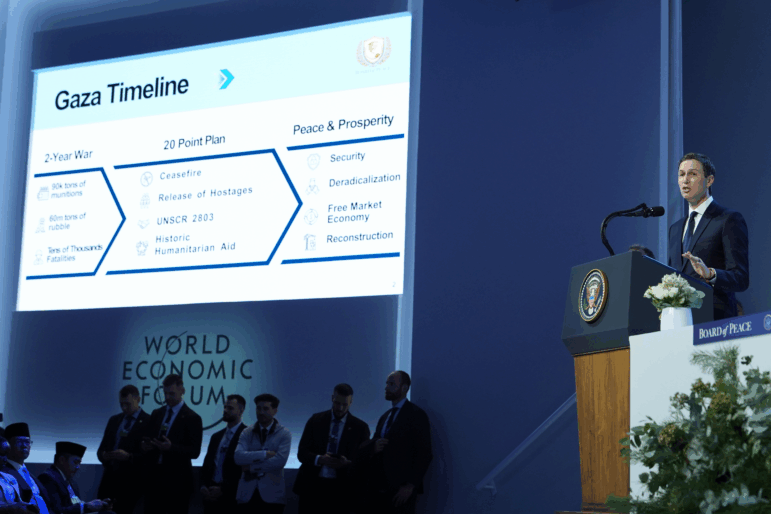

“We’ve already started removing the rubble and doing some of the demolition,” Jared Kushner, President Trump’s son-in-law, said while presenting the plan recently in Davos, Switzerland.

“And then ‘New Gaza.’ It could be a hope, it could be a destination, have a lot of industry and really be a place that the people there can thrive, have great employment,” he said.

The Gaza Strip is only 25 miles long and about 4 to 7 miles wide. It was home to around 2.2 million people before the war, all living in densely packed cities and refugee camps. Now, nearly everyone lives in makeshift tents or bombed-out homes that are at risk of collapse. The World Bank estimated in 2024 the cost of damage to critical infrastructure alone was more than $18 billion.

The plan laid out by Kushner rests on Trump’s ceasefire deal, which demands that Hamas decommission its weapons as Israel withdraws from Gaza in phases. Reconstruction would only commence in areas of Gaza where Hamas is fully disarmed, or already emptied of Palestinians and under Israeli military control.

This “New Gaza” plan, however, makes no reference to land deed transfers nor how new housing would be allocated to Palestinians. It also does not say how families will be uprooted from existing buildings that the plan would demolish, particularly in central Gaza and parts of western Gaza City where many buildings are still intact.

Critics, including people NPR interviewed in Gaza, say it erases Gaza entirely and turns it into an investment opportunity atop the ruins of what a U.N. commission determined was a genocide committed by Israel. Israel denies the allegation, and is fighting war crimes charges internationally.

It’s unclear if any Palestinians were consulted in the “New Gaza” vision unveiled by Kushner, but he says Israeli real estate investor, Yakir Gabay, played a key role in crafting the plan. Both men are on the White House-appointed Gaza Executive Board that will oversee the plan and report to Trump’s Board of Peace.

Here are five things to know about the “New Gaza”:

1. Less space for housing than before the war

Kushner’s plan envisions four district-like areas for Palestinians to live in, nestled between large green areas for parks and industrial zones that appear equal in size or larger than the areas designated for housing. These industrial zones would create more than half a million jobs for Palestinians in Gaza, according to the plan.

A report published by the U.N.-Habitat agency in 2024 said 87% of Gaza was urban area and nearly all the rest was refugee camps, describing the territory as “fully urbanized.”

That means the plan leaves far less room for Palestinian housing than existed before the war, suggesting a smaller population in Gaza.

NPR asked the White House-appointed Gaza Executive Board whether the plan takes into account the full population of Gaza. A spokesperson, who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss details of the plans, said the figures presented for the first phase of reconstruction are “just the start,” without elaborating.

2. Reshaped cities with some no longer existing

The plan lays out phases for rebuilding, starting with the south. Two areas labeled as “Gaza City” to the north would be built in the last, fourth phase.

Gaza’s residential areas would be divided into quadrants, labeled as Rafah, Khan Younis, Center Camps and Gaza City. They would be disconnected from one another, and divided by large green areas designated for parks, agriculture and sports facilities. Only a few main roads connect them.

The plan would erase northern Gaza cities and refugee camps like Beit Lahia and Jabalia, replacing them with agricultural areas and zones designated for data centers and advanced manufacturing. It would raze other parts of Gaza to the ground to be rebuilt.

“You’re going to remove people’s homes and put parks instead, but did you ask a single person in Gaza to do this?” said Rami Abdel-Aal, a resident of Gaza whose home in Rafah was demolished in an area now occupied by the Israeli military that’s being razed to build the first such community.

“We only want one thing: Leave us to rebuild,” he said. “We don’t want anything from you. Just leave us to rebuild.”

3. A new airport, but no independent land crossing

In the vision laid out by Kushner, southern Gaza would have an airport, a train and logistics hub, and a port — all nonexistent at the moment.

Gaza has been besieged by Israel since Hamas took over rule of the territory in 2007. People can only exit or enter Gaza by land with Israeli approvals through border crossings Israel controls.

But under the plan, Gaza’s single border crossing with Egypt, known as the Rafah crossing, would no longer be geographically distant from Israel. It would be moved south to the tip of Gaza and renamed a “trilateral crossing,” touching both Egypt and Israel.

Egypt has not commented on the plan, and throughout the war has rejected Israeli control of Rafah.

4. A “New Rafah” as the center of gravity

Gaza’s southernmost city of Rafah had long been a quiet border town known mostly for its smuggling tunnels with Egypt, but Kushner’s plan envisions the city as Gaza’s logistics and possibly administrative hub.

Rafah, today, is nearly void of residents and under Israeli military occupation. Palestinian militias armed by Israel and opposed to Hamas operate in the area.

Under the “New Gaza” plan, Rafah has among the most housing of all the areas in Gaza, suggesting the population, which before the war was heavily in the north near Israel, would be pushed south.

Described as “New Rafah,” there would be 100,000-plus permanent housing units, according to Kushner’s plan. Prior to the war, all of Gaza had nearly 600,000 apartments and housing units for 2.2 million people, according to the U.N.-Habitat report. It noted a critical housing shortage even before Israeli attacks destroyed or damaged more than 90% of homes.

The new plan also says there will be some 200 educational centers in “New Rafah.” Before the war, Gaza had around 700 schools, including private, public and U.N.-school buildings, according to figures obtained by NPR from the U.N. relief agency for Palestinians, known as UNRWA, and the Palestinian Education Ministry. In addition, there were 17 higher education institutions, or universities.

An Israeli official told NPR the ground in Rafah is being prepared to be cleared of unexploded ordnance and tunnels in order to set up temporary housing. The official spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss details of the preparations. The official said that Kushner and U.S. special envoy Steve Witkoff have asked Israel to accelerate operations clearing rubble in Rafah, where a neighborhood funded by the United Arab Emirates would be built to house thousands of civilians from Gaza.

The UAE’s government did not respond to a request for comment.

5. A coastline for tourists and investors

The entirety of Gaza’s Mediterranean coastline is designated under the plan as an area for “coastal tourism” with 180 “mixed use” towers.

The visuals for the plan are stark, and look nothing like Gaza. Futuristic towers would form a new skyline along Gaza’s coast, resembling a billionaire’s playground much like Dubai.

Palestinian residents of Gaza would likely be priced out of this prime, new real estate. Gaza’s coastline before the war included apartment buildings, local hotels, cafes and public beaches. These beaches are people’s only escape from Gaza’s otherwise densely packed terrain.

Anas Baba in Gaza City, Ahmed Abuhamda in Cairo and Itay Stern and Daniel Estrin in Tel Aviv contributed to this report.

Transcript:

A MARTÍNEZ, HOST:

President Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, has a vision for a new Gaza. The real estate developer who also acts as a U.S. envoy to the Middle East presented a slide deck showing a rebuilt territory. It showed a mix of futuristic skyscrapers and industrial zones. NPR’s correspondent in Dubai, Aya Batrawy, is covering this. All right, so a new Gaza. How would that work?

AYA BATRAWY, BYLINE: This vision is ambitious, and Kushner says it’s based on free market economy principles to empower the people of Gaza with jobs and economic prosperity. Have a listen.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

JARED KUSHNER: We think this could be done in two, three years. We’ve already started removing the rubble and doing some of the demolition. And then new Gaza. It could be a hope, it could be a destination, have a lot of industry and really be a place that the people there can thrive, have great employment.

BATRAWY: So he says to do this in two or three years, there has to be security and new governance in order to attract investors, and he’s calling on donors to come forth and trust the Trump plan. Now, already, the Trump administration, which pushed Israel and Hamas to agree to the current ceasefire, is backing a new committee of Palestinian technocrats to take over administration of Gaza. They would be working under a new Board of Peace that Trump presides over. And the U.S. plan also requires that militant groups in Gaza lay down their weapons before any rebuilding starts. And Kushner says this is the only plan for Gaza, that there is no plan B.

MARTÍNEZ: OK. So that’s how it might work. What might it look like?

BATRAWY: OK. The slide show Kushner presented shows an airport which Gaza currently doesn’t have. It shows a flourishing seaport, data centers and industrial zones for advanced manufacturing where more than half a million jobs would be created. This new Gaza would also have huge parks, farmland and even trains. But it’s really the skyscrapers on the coast that are most astonishing, A. They resemble Trump’s Gaza Riviera plan from about a year ago, and it looks like where I’m speaking to you from in Dubai – like its most luxurious Billionaire’s Row, with high-rise towers and loft-style apartments, floor-to-ceiling windows that look onto the Mediterranean.

MARTÍNEZ: Now, Kushner mentioned how they’re starting to remove rubble. What are the conditions in Gaza like now?

BATRAWY: Gaza is still under a blockade. International journalists like myself cannot enter freely. Major aid groups are being barred, and basics, like school supplies, are still not being allowed in by Israel. Most people are living in makeshift tents and babies have died in the cold this winter. Israeli troops still occupy more than half of Gaza and have killed nearly 500 Palestinians in the last three months of ceasefire, according to Gaza’s health ministry. So what this plan does not address is the continued Israeli occupation of Gaza or statehood, which remains a key demand of Palestinians. So short of the U.S. wrangling control of Gaza from Israel, it’s unclear how this new Gaza can replace the current reality.

MARTÍNEZ: Any reaction from the people in Gaza over this?

BATRAWY: You know, the plan laid out by Kushner mentions a hundred thousand plus permanent homes in Gaza, but there are 2 million people in Gaza today. And the U.N. says there were close to 600,000 homes and apartments in Gaza before the war. So this plan seems to envision Gaza with a lot fewer Palestinians. Now, NPR’s reporter, Anas Baba, spoke to Palestinians in Gaza and showed them some of the slides. Ghada Duhair (ph), a mother of four, told him the images look nice at first glance, but a closer look shows it’s all parks and economic zones. Where have our houses gone? She says.

GHADA DUHAIR: (Non-English language spoken).

BATRAWY: She says, “this is not Gaza. All our rights and homes are gone in this plan.” She says, “just bring in aid and open the border for us.” She says, “the plans being drawn up are for investors and tourists, not for the people who live here.” And Kushner says this new Gaza master plan was drawn up with the help of Yakir Gabay, an Israeli billionaire real estate investor. It’s unclear if any people from Gaza were consulted in this plan.

MARTÍNEZ: All right. That’s NPR’s Aya Batrawy in Dubai. Thank you very much.

BATRAWY: Thanks, A.