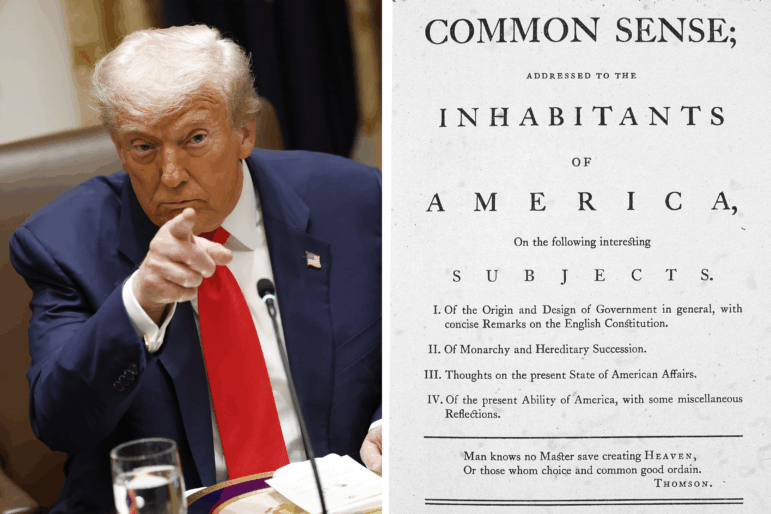

The idea of “common sense” has been central to American politics since the founding of the United States. Politicians still use the phrase all the time — and perhaps none more so than President Trump.

Just this month at a Cabinet meeting, he used the phrase when he again recommended that pregnant women not take Tylenol.

“There’s something going on, and we have to address it. And so, I’m addressing it the best I can as a nondoctor, but I’m a man of common sense,” he said.

He also used the term when he cast doubt on the monthly jobs report on CNBC in August: “It’s totally rigged. Smart people know it. People with common sense know it.”

The White House has also used it to explain the current government shutdown.

“Not enough Democrats voted for this common sense, clean continuing resolution to keep the government open,” White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt recently told NPR’s Morning Edition.

This isn’t exactly new. “Common sense” is such a widely used political phrase that University of Pennsylvania history professor Sophia Rosenfeld wrote an entire book on it. And yet, she says, Trump’s usage of it is unique.

“He uses it more than almost anybody else in American politics,” she said. “Although, of course, it has a really old origin story.”

That goes back to Thomas Paine, in his 1776 pamphlet “Common Sense,” which made the case to the earliest Americans that British rule of the colonies was wrong. And in that, she says, Paine had hit upon the populist appeal of the phrase.

“It invokes some kind of primordial basic sense of ordinary people, a kind of lived experience that should transcend what the official or elite position is on something and particularly should transcend book learning and school learning,” she said.

And Trump often invokes that dichotomy of common sense vs. academic smarts.

Speaking to military leaders in Quantico, Va., last month, Trump differentiated his administration from Joe Biden’s, saying that Biden was surrounded by “radical left lunatics that are brilliant people but dumb as hell when it came to policy and common sense.”

The phrase appeals more to several demographics that strongly align with Trump, says Frank Luntz, a longtime Republican strategist.

“Common sense is a higher priority to those who live in rural communities than those in the urban areas. Common sense does better among older voters than it does among younger voters,” he said. “And I think the reason why is that it reminds people of a more simple past.”

And that understandably appeals to people who want to make America great again.

But Democrats use the phrase too. President Barack Obama tried to pass what he called “common sense gun reform.”

Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., used it this year on her Fighting Oligarchy Tour with Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt.

“I believe that in the wealthiest nation in the history of the world, if a person gets sick, they shouldn’t go bankrupt. Common sense,” she told a crowd at Arizona State University in March.

One way to look at “common sense” is as an attempt to signal that a policy isn’t extreme and could have broad appeal.

But as Luntz points out, it can also be a cudgel, especially in Trump’s hands.

“For him, common sense has an even broader meaning,” he said. “It’s not just that you’re right for the right reasons. It’s also that the other side is wrong for being ideological, for being political or being outside the mainstream.”

Rosenfeld has a similar take.

“It’s also potentially rather demagogic,” she says of the phrase. “Common sense also suggests not that there’s another side to it. The other side in a debate with common sense is nonsense.”

And in that sense and others, common sense can be considered one of the most powerful pieces of rhetoric the MAGA movement has found.

To Rosenfeld, Trump especially uses the phrase to try to excuse norm-shattering behavior — like a September social media post that Chicago was “about to find out why it’s called the Department of War.”

Here’s how Trump explained that to a reporter: “We’re going to clean up our cities. We’re going to clean them up so they don’t kill five people every weekend. That’s not war — that’s common sense.”

“Common sense” gives the impression of timeworn policy ideas, even if the policy — mass deployment of the National Guard into U.S. cities — was previously unthinkable.

Transcript:

AILSA CHANG, HOST:

The idea of common sense has been central to American politics since the founding of the U.S. Politicians still use the phrase all the time, perhaps none more so than Donald Trump. NPR White House correspondent Danielle Kurtzleben reports on how the phrase became one of the MAGA movement’s central arguments.

DANIELLE KURTZLEBEN, BYLINE: President Trump seems to frame nearly everything he believes as common sense, like his recommendation that pregnant women not take Tylenol.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: There’s something there. There’s something going on, and we have to address it. And so I’m addressing it the best I can as a nondoctor, but I’m a man of common sense.

KURTZLEBEN: Or when he cast doubt on the monthly jobs report talking to CNBC’s Joe Kernen.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

TRUMP: It’s totally rigged. Smart people know it. People with common…

JOE KERNEN: OK.

TRUMP: …Sense know it.

KURTZLEBEN: The White House has also used it to explain the current government shutdown. Here’s press secretary Karoline Leavitt speaking to NPR’s Morning Edition recently.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR CONTENT)

KAROLINE LEAVITT: Not enough Democrats voted for this common sense, clean, continuing resolution to keep the government open.

KURTZLEBEN: This isn’t exactly new. Common sense is such a widely used political phrase that University of Pennsylvania history professor Sophia Rosenfeld wrote an entire book on it. And when it comes to Trump…

SOPHIA ROSENFELD: He uses it more than almost anybody else in American politics, although, of course, it has a really old origin story.

KURTZLEBEN: That goes back to Thomas Paine in his 1776 pamphlet “Common Sense,” which made the case to the earliest Americans that British rule of the colonies was wrong. And in that, she says, Paine had hit upon the populist appeal of the phrase.

ROSENFELD: It invoked some kind of primordial basic sense of ordinary people, a kind of lived experience that should transcend what the official or elite position is on something and particularly should transcend book learning and school learning.

KURTZLEBEN: And Trump regularly invokes that. Here he was speaking to military leaders at Quantico last month, differentiating his administration from Joe Biden’s.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

TRUMP: People that surrounded him, radical left lunatics, that are brilliant people but dumb as hell when it came to policy and common sense.

KURTZLEBEN: The phrase appeals more to several demographics that currently strongly align with Trump says Frank Luntz, a strategist who has worked with Republicans.

FRANK LUNTZ: Common sense is a higher priority to those who live in rural communities than in those in the urban areas. Common sense does better among older voters than it does among younger voters. And I think the reason why is that it reminds people of a more simple past.

KURTZLEBEN: Which understandably appeals to people who want to make America great again. But Democrats use the phrase too. President Barack Obama tried to pass what he called common sense gun reform. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez used the phrase this year on her Fighting Oligarchy Tour with Senator Bernie Sanders.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

ALEXANDRIA OCASIO-CORTEZ: I believe that in the wealthiest nation in the history of the world, if a person gets sick, they shouldn’t go bankrupt – common sense.

KURTZLEBEN: One way to look at common sense is an attempt to signal that a policy isn’t extreme and could have broad appeal. But as Luntz points out, it can also be a cudgel, especially in Trump’s hands.

LUNTZ: For him, common sense has an even broader meaning. It’s not just that you’re right for the right reasons. It’s also that the other side is wrong for being ideological, for being political, for being outside the mainstream.

KURTZLEBEN: Rosenfeld has a similar take.

ROSENFELD: It’s also potentially rather demagogic. Common sense also suggests not that there’s another side to it. The other side in a debate with common sense is nonsense.

KURTZLEBEN: And in that sense and others, common sense can be considered one of the most powerful pieces of rhetoric the MAGA movement has found. To Rosenfeld, Trump especially uses the phrase to try to excuse norm-shattering behavior, like a September social media post saying, quote, “Chicago about to find out why it’s called the Department of War.” Here’s how Trump explained that to a reporter.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

TRUMP: We’re going to clean up our cities. We’re going to clean them up so they don’t kill five people every weekend. That’s not war. That’s common sense.

KURTZLEBEN: Common sense gives the impression of time-worn policy ideas, even if the policy – mass deployment of the National Guard into U.S. cities – was previously unthinkable.

Danielle Kurtzleben, NPR News.