Migrant stories have two parts: the leaving of an old life, and the building of a new one.

Pat Rush’s “old life” started in Arkansas. She was born in 1935 and her family worked as laborers picking cotton. It was hard work. By the time she was seven, she was working in the cotton fields too.

“I remember dirt running down my face, snot running out my nose, and I was wet and sweaty,” she told Radio Diaries. “I was a little fat girl and I always had a bad haircut or something. In my mind I thought, ‘There’s more to life than being this poor.’”

Rush’s father had died a few years earlier, leaving her mom to raise seven kids on her own. One day her mom made a decision that would change Rush’s life.

“We were picking cotton when Mama just stood up, and I can remember pretty much the words she said: ‘Pick up your sacks, kids, we’re going to California.’”

They found a ride and loaded the car with whatever provisions and household items would fit and drove west.

Going to California

Rush and her family left Arkansas in the wake of one of the largest migrations in U.S. history.

During the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, millions of desperate Americans abandoned their homes, farms and businesses to look for work elsewhere.

Though Rush’s family left after the Dust Bowl years were officially over, they took the same path — traveling Route 66, which the migrants called “the Mother Road,” until they reached California.

Rush remembers the day they arrived.

“We stopped there on the road, got out of the car and looked down at the San Joaquin Valley and it was lush green everywhere as far as your eyes could see,” she says. “Oranges and grapes and all kinds of crops. I think we were in awe of it. I’d never seen anything that beautiful before.”

Rush says her mother thought once they got to California, everything would be fine. That there would be plenty of jobs and food and places to stay. But they soon realized that wasn’t the case. Rush says the biggest crisis for them was finding a place to live.

Fortunately, her family found a spot in a government camp.

The government camp

In response to the influx of migrants to California, the federal government built a series of camps to provide safe housing, clean drinking water and other services. Some camps had their own schools for the migrant workers. Rush would later go to grade school at the Weedpatch Camp, which was memorialized in John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath.

She remembers the camp felt scary and huge at first, with rows and rows of tents and cabins. But at the same time, she was excited. There was a big building that had showers and toilets.

“It was the very first time I had ever seen an indoor toilet. So I thought we had moved to the big time,” she says.

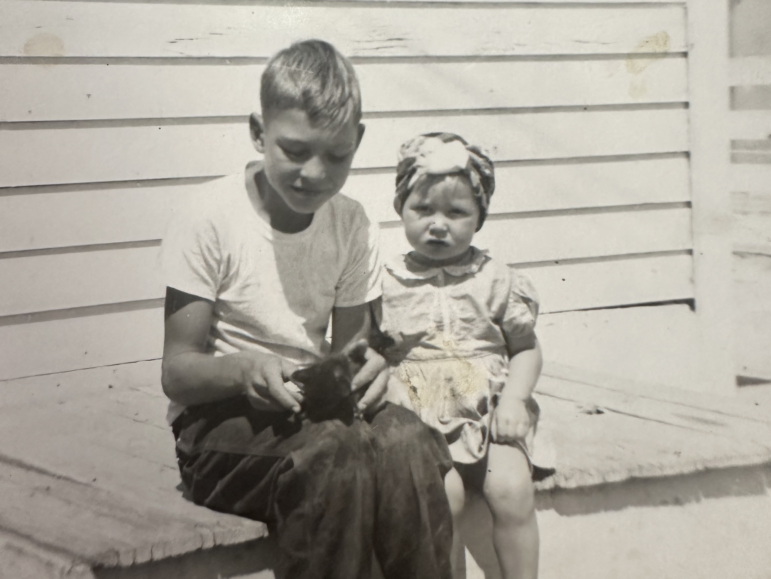

Her family found work in the fields, picking potatoes, cotton and grapes. But Rush’s job was to stay home and take care of her baby sister and clean the cabins.

“I learned to make cornbread. It was kind of like playing house,” she says.

Life in the camp was orderly. The residents elected their own representatives and made most of the rules. Rush says if you were behind on your rent it would be announced over the camp loudspeaker.

What she liked most about living in the government camp was that everyone was as poor as her own family was.

“I knew I lived in as nice a house as anybody,” she says. “One might be more dirty or cleaner than the other one, but you still lived in a government camp. And I liked that feeling. Of feeling equal.”

Rush says that wasn’t the case outside of the camp. In town, many of the new arrivals felt discriminated against by local residents and business owners.

“I didn’t feel like they wanted us here. I would see them snicker because we talked different, or dressed different. I think they thought we were lower class people, almost like dirty or ignorant,” she says.

Rush was shy and never felt good enough. High school was especially hard for her.

“Here’s these little girls, with matching cashmere socks and sweaters, and I thought, ‘That’s what I wanna be.’ But one day I said, ‘To hell with this.’ I thought, ‘You’re as good as anyone. You’re as pretty as any of these other girls. And you’re smart as they are. So you hold your head up and walk down the hall and be yourself.’ And that’s when I first got some guts about me.”

Rush and her family moved out of the government camp when she was 15. She got married the next year to another farm laborer and had a baby when she was 17 and another at 18.

She says she wanted to get a house and “be normal,” but that dream felt out of reach. It wasn’t until her husband got a job in the oil fields, and, eventually, a better job operating heavy equipment that they were able to buy their first house.

“With indoor plumbing,” says Rush, laughing. “I felt like we were rich.”

Looking back

Rush is now 89. Her husband died in 2019. Life is like a book, Rush says, and she’s on the last chapter. But she likes this chapter. Her daughters live nearby and she feels free to do as she likes.

“I can see, I can walk, I can hear, I can go to church or I can have a beer,” she says. “And I think about way, way back in my life when I was a little girl in Arkansas, I would never have dreamed that I would have a nice house like I do. I don’t have a fancy house, but I have a nice house with a big backyard.”

The word “home” is big and important, Rush says. And today there are a lot of Mexican migrant workers in her area who do field work just like she used to do. Rush says some of them live in the same camp area where she used to live.

“I think about them out in the fields, working and living in the camp,” she says. “And I feel for them. Because I know how that feels.”

The audio story was produced by Joe Richman of Radio Diaries and edited by Ben Shapiro and Deborah George.

You can hear the full version on the Radio Diaries podcast.

Transcript:

JUANA SUMMERS, HOST:

Today from Radio Diaries, the story of a woman who was part of one of the largest migrations in U.S. history. Millions of desperate Americans abandoned their homes, farms and businesses during the dust bowl of the 1930s. The last drought ended by 1940. Pat Rush’s family were farm laborers exhausted by trying to make ends meet. So they left Arkansas and followed the hundreds of thousands who had traveled Route 66 to the San Joaquin Valley in California. There, the federal government had built resettlement camps to help deal with the influx. Migrant stories have two parts – the leaving of an old life and the building of a new one.

PAT RUSH: OK, well, my name is Pat Rush, and I grew up in Arkansas. We lived way out in the country. And my whole family were cotton pickers. We didn’t own the fields. You would get paid by the pound.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

RUSH: (Singing) I’ve done everything I could…

As far back as I can remember, I loved to sing. So I’d kind of pretend the cotton fields were a big audience, and I would sing.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

RUSH: (Singing) I can leave now knowing I have done my part.

That’s me singing right there.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

RUSH: (Singing) I’m going to be…

(Singing) Fancy free. No one to tie my feet to the ground.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

RUSH: (Singing) No love for me tomorrow.

I remember my sister, Fran and Bonnie and I – we were picking cotton with Mama. And out of the clear blue, she just stood up, and I can remember pretty much the words she said. She said, pick up your sacks, kids. We’re going to California. And I thought, that sounds good to me. In my mind, I knew there was better stuff out there ’cause I thought, there’s more to life than being this poor.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED NARRATOR: A hundred thousand families on wheels, seeking three square meals a day. These people take pilgrimage to the promised land of plenty, the lush valleys of California.

RUSH: When we first got to California on Route 66, and when we got to the top of the mountain, I remember we stopped there on the road, got out of the car and looked down in the San Joaquin Valley. And it was lush green everywhere, as far as your eyes would see, oranges and probably grapes and all kind of crops. And it – I think we were in awe of it. I’d never seen anything that beautiful before.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

UNIDENTIFIED SINGERS: (Singing) And I ain’t going to be trading this away (ph).

RUSH: I know Mama thought, when we got to California, her and her kids would be fine – plenty of work for everybody, places to live – but that wasn’t true. It was a sad situation, you know? But the big crisis would be trying to find a place to live. And that’s when we moved into a camp that – it was a government camp.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED NARRATOR: So government camps, for a nominal rent, payable in money or in work hours, provide sanitary shelter sites for these virtual refugees.

RUSH: When we first pulled into the camp, I remember and – people sitting outside kind of staring – you know what I’m saying? – looking like, more new people coming in or whatever. There was tents. There was cabins. There was this row of cabins here, a row here. It looked huge to me. But I was excited to have arrived to live in a place where there was kids so close, that you lived real close to all your neighbors, like, right here. And there were showers and toilets, and that’s the very first time I’d ever seen a indoor toilet. So I thought we had moved to the big time.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED NARRATOR: Here, the migrant and his family, fortunate enough to find shelter on U.S. property, can maintain their self-respect while seeking market for their labor.

RUSH: Everybody was working in the fields. My mama, my sisters, and my brother – everybody’s picking up potatoes, cotton or grapes. But my job was to stay home and take care of my baby sister and do kind of what little women do, I guess. Clean the cabins – I kept them really clean, and then I learned to make cornbread, and I was so proud of myself. It was kind of like playing house.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED CHILDREN: (Singing) Over here in the government camp, that’s where we get our government stamps, over in that little raghouse home.

RUSH: Everybody in the government camp, all your neighbors, was as poor as we were. I knew I lived in as nice a house as anybody else there. It might – one might be more dirty or cleaner than the other one, but you still lived in a government camp. And I liked that feeling, of feeling equal. But then as you get out in public, everybody’s not from the camp.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

RUSH: On weekends, we could walk from the camp to Lamont, a little town, and we probably stood out like a sore thumb. The business owners were California people, and I didn’t feel like they wanted us here. And I would – could see them, you know, like, kind of snickering at you or something ’cause you talked different and dressed maybe a little different. I think they thought we were a little bit lower-class people, almost, like, dirty or ignorant.

That was a hard time in my life because I was so shy. I never felt good enough, especially in high school. When I started high school, I was still this little intimidated girl ’cause here’s these little girls in matching cashmere socks and sweaters, and I thought, that’s what I want to be. But one day, I was in the ninth grade, and I thought, to hell with this. I think I was angry. I thought, you’re as good as anyone. You’re as pretty as any of these other girls, and you’re smart as they are. So you hold your head up and walk down the hall and be yourself. And that’s when I first got some guts about me.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

RUSH: (Singing) Well, I saved up all my money. I’m going to leave this town. I’m not going to live here no more. I’ve been dreaming…

Well, you know, to end this conversation, life’s like a book, and I’m on the last chapter of my life, and I like it. I can see. I can walk. I can hear. I can go to church, or I can have a beer. And I think about way, way back in my life when I was a little girl in Arkansas. I would never have dreamed that I have a nice house like I do. I don’t have a fancy house, but I have a nice house, a house on a street with indoor plumbing. And so home is a – that is a big, big word.

And, like, there’s a lot of Mexican people here that do field work, just like we did. Some of them still live down in the camp area where we used to live. I think about them out in the fields working and living in the camp, and I feel for them ’cause I know how that feels.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

RUSH: (Singing) So don’t look for me tomorrow ’cause I’ll be gone. I already paid my dues of settling down.

SUMMERS: Pat Rush in Bakersfield, California. The government camps around Bakersfield were immortalized in John Steinbeck’s “Grapes Of Wrath.” Today, some of them still house migrant farmworkers from Mexico. Our story was produced by Joe Richman of Radio Diaries and edited by Ben Shapiro with music from Pat Rush herself. You can find the full version of this story on the Radio Diaries podcast.