In the decades I have covered the Supreme Court, I have read lots of books written by justices, and with a couple of notable exceptions, they are…sigh, pretty boring.

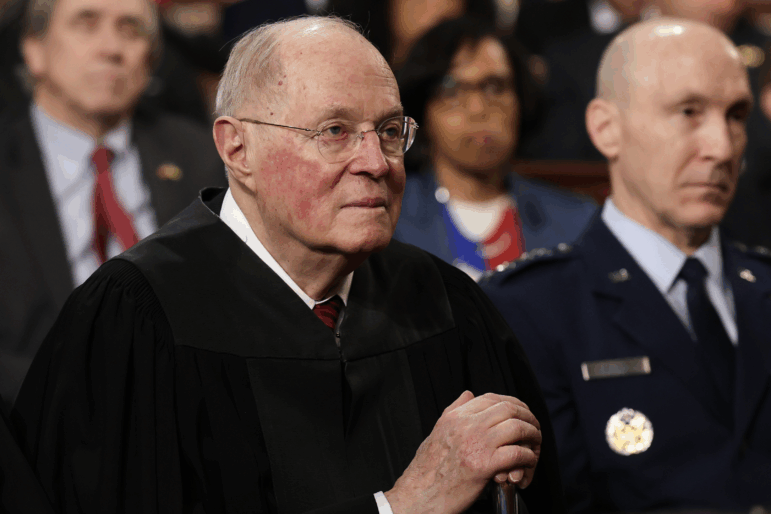

Retired Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy, however, has written a very interesting book — “Life, Law, & Liberty,” scheduled for release Oct. 14 — because he reveals more than usual about himself and his 30 years of service on the nation’s highest court — a period of time in which he was often the “swing justice” whose vote was determinative in controversial cases ranging from same-sex marriage to, campaign finance, affirmative action, and abortion.

Kennedy and Justice Sandra Day O’Connor for much of their overlapping tenures represented the ideological center of the court at a time when the institution became increasingly conservative. Interestingly, both justices were products of the West, much like the President who appointed them, Ronald Reagan. And both justices viewed their Western origins as essential to the their personalities and views. Both started out as pretty firm conservatives, but eventually saw the court transform into a far more conservative group of justices. Or as Kennedy puts it in his book, “The cases swung, not me.”

Concerned about the country

In an interview with NPR to be aired in October, Kennedy said that he is “very worried” about America today.

“We live in an era where reasoned, thoughtful, rational, respectful discourse has been replaced by antagonistic, confrontational conversation,” he said, adding that “Democracy is not guaranteed to survive.”

Indeed, he says that he is worried even about the tone of some Supreme Court opinions.

“It seems to me the idea of partisanship is becoming much more prevalent and more bitter,” he said. “And my concern is that the court in its own opinions…has to be asked to moderate and become much more respectful.”

When he retired from the court in 2018, Kennedy told a small group of journalists that he was confident that the court’s major decisions would remain intact. But when I asked him if he still thinks that is true, he demurred.

Though Kennedy, in close cases, voted most often with the court’s conservatives, perhaps most revealing in the book are his accounts of how and why he cast decisive votes with the court’s liberals on abortion and same-sex marriage. Of the two issues, it turns out that same-sex marriage was easier for Kennedy to resolve, but harder on his relationship with his conservative colleague, Justice Antonin Scalia.

Gay marriage decision

Starting in 1996 Kennedy wrote every major decision about gay rights, culminating in 2015 when he wrote the court’s majority opinion in Obergefell v. Hodges declaring that same-sex couples must be allowed to marry everywhere in the country.

“No union is more profound than marriage, for it embodies the highest ideals of love, fidelity, devotion, sacrifice and family,” he wrote.

Kennedy says that perhaps the most persuasive argument for gay marriage came with his realization that many states barred gay couples from adoptions, so that only one could be the legal parent, and the other had no legal right to make decisions for the child, sign school papers for the child, in some cases could not visit the child in the hospital, and the children could not say they had two parents, which was “terribly demeaning for the children of gay parents.”

That was the situation faced by “hundreds of thousands of children of gay parents,” he observed in our interview. “That was eye-opening for me, and it was very important in influencing me for the result.”

It was the gay marriage cases, however, that for almost a year led to a rupture with his colleague, Justice Antonin Scalia. The break came over Scalia’s dissenting opinion in the same-sex marriage case in which he wrote that if ever he were to join an opinion like Kennedy’s “I would hide my head in a bag.” According to Kennedy, the other conservatives thought the dissent “offensive” and “intemperate” and tried to get Scalia to modify it. But they failed, prompting Chief Justice John Roberts to write the lead dissent.

Kennedy says that while he was able to “shrug off” the Scalia dissent, his children and their spouses “were devastated” by its tone.” And by the beginning of the next term Scalia, known to all as Nino, “rarely came to lunch” with his colleagues and no longer stopped by Kennedy’s chambers to chat.

Months went by and then one day in February of 2016 Scalia “came down the long corridor of the court to my chambers to talk.” Once there, “he turned to the subject on both our minds: our own relationship. Nino said he had come to regret deeply his Obergefell dissent” and he apologized for being intemperate. “The visit became a pleasure, even a landmark for us,” writes Kennedy. “Neither of us was big on hugging but we hugged, both of us smiling.”

Scalia was leaving shortly for a hunting trip in Texas, but the two men pledged that when he returned, they and their wives would get together again. Kennedy recalls that he told Scalia not to overschedule himself, and Scalia promised that this would be his last long trip.

Those parting words were the last they ever spoke to each other. About a week later, Scalia died in his sleep while on that hunting trip. “If friendships are slipping away, we must renew them soon, lest time does not permit us to celebrate them for long,” Kennedy writes.

Record on abortion

The other emotional legal issue that Kennedy talks about in the book is abortion. A devout and Mass-attending Catholic, Kennedy then, as now, views abortion as a moral wrong. And at one point he was so conflicted that he even considered resigning. “Another life is involved, one that cannot speak for itself. For many of us the unborn child cries out from the womb, cries out with a soulful voice to us and the law: let me exist, let me live,” he writes.

Ultimately, though, he concluded that “a moral wrong is not necessarily a legal wrong, nor do my own personal views control what I must decide as a judge.” As a co-author of the decision that upheld the right to abortion, he writes, “The constitution promises…a realm of personal liberty which the government may not enter” and among those decisions, the mother’s choice to bear a child is among the most personal known to our law.”

The abortion decision that Kennedy co-authored is exhibit A of his opposition to the doctrine that today dominates the conservative Supreme Court: originalism. Six members of the court to a large degree have embraced the idea that the Constitution should be interpreted by following the words in the Constitution at the time the it was ratified, and in some cases the way it was interpreted after the post-Civil War amendments to the Constitution guaranteeing equal protection of the law.

Views on originalism

Kennedy has a different view.

“Liberty must be understood over time,” he said in our interview, adding that it helps little to do what originalists do, refer to dictionaries of the 1700s to figure out what the meaning of the Constitution was at the time it was adopted. In the book, he leads the section on liberty by quoting from his same-sex marriage opinion: “The nature of injustice is that we may not always see it in our own times. The generations that wrote and ratified the Bill of Rights and the Fourteenth Amendment did not presume to know the extent of freedom in all its dimensions, and so they entrusted to future generations a charter protecting the right of all persons to enjoy liberty as we learn its meaning.”

Or as he puts in in the book, “In my view the framers of the constitution were not so self assured as to think they knew what the spacious term ‘liberty’ should mean in all its reach. If they had been certain, they would have written a more detailed explanation” but the Framers were “cautious enough and modest enough” that they “intentionally chose capacious terms that would inspire and protect freedom.”

A man of the American West

While some conservative scholars are less than kind to Kennedy over his changes of heart on some issues, for others it may be somehow reassuring to hear his account of those changes of mind. How, for instance, he initially thought that juvenile killers should be eligible for the death penalty, but later changed his mind for a variety of reasons, among them that the U.S. was among fewer than a handful of nations to permit such punishment. And because studies of the brain indicate that “the urge to act without thinking is much more prevalent among minors.”

Even as much of Kennedy’s book is serious, there are some hilarious moments, too. My favorite is the red emergency phone in his chambers that never rang. Then one day it did. It was a prisoner in Ohio, who somehow had gotten the telephone number. The court police quickly said they would change the number, but Kennedy said he enjoyed the occasional chats with the prisoner, who told the justice which rulings he agreed with and which ones he disapproved of.

There is a great deal more in Kennedy’s book—about his family, the court, his upbringing in Sacramento, Calif., in the ’30s and ’40s, and about his father, who took the unpopular position of opposing the Japanese internment during World War II. Kennedy, who at 89, is still a tall strapping man, was by his telling, a sickly kid whose father and mother taught him to read at an early age, and had him read Shakespeare aloud in the car when he was less than 10 years old.

After his father died unexpectedly in 1963, Kennedy, who had just begun his legal career in San Francisco, moved back to his family home in Sacramento to take over his father’s law practice. He was just 27 years old, and would remain in the place he loved for another 25 years. At age 38 he became the youngest federal appeals court judge in the country, but left Sacramento only when appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1988.

In those days, Kennedy observes, Sacramento was a small town of about 130,000 people, and through his eyes, you can almost smell the air, see the scenery and feel the West. Those are the poetic parts of the book.

Nina Totenberg has covered the Supreme Court for NPR since 1975