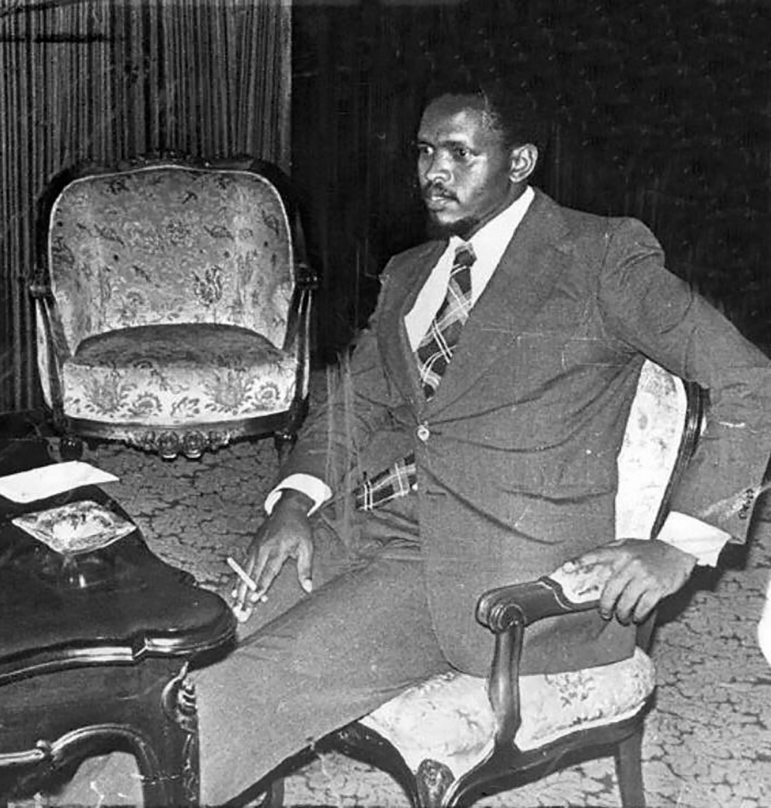

JOHANNESBURG, South Africa— “September ’77, Port Elizabeth weather fine. It was business as usual, in police room 619,” go the opening lines of singer Peter Gabriel’s famous anti-apartheid anthem from 1980 about murdered South African activist Steve Biko.

Apartheid police always maintained that the Black Consciousness Movement leader died after accidently hitting his head against his prison cell wall. Now the South African government wants to establish what really happened in “room 619,” where Biko spent almost a month in custody naked and shackled in leg irons.

On Friday, the 48th anniversary of the liberation icon’s death, the government reopened the inquest into the 1977 case, in what Luxolo Tyali, a spokesman for South Africa’s National Prosecuting Authority (NPA), said was an effort “to address the atrocities of the past and assist in providing closure to the Biko family and society at large.”

Biko was arrested in Eastern Cape province for violating a ban restricting his movements and taken to prison in the city of Port Elizabeth, now renamed Gqeberha. “It was only after 24 days in custody that medical assistance was sought for him after ‘foam’ was noted around his mouth,” the NPA said in a statement this week.

“He was loaded unconscious, still naked and shackled, into the back of a police Land Rover, and transported to a prison hospital in Pretoria, 1,200 kilometres away. He died outside a Pretoria hospital on 12 September 1977 at the age of 30,” it continued.

The case of death was recorded as extensive brain injury and acute kidney failure. His interrogators from the notorious apartheid special police branch said at the 1977 inquest that Biko had been injured when he banged his head against the wall. An Associated Press report at the time said “the police testimony brought whistles and gasps from black spectators.”

Biko became an icon in the West, and Denzel Washington played him in the 1987 film Cry Freedom.

Thirty years after the original inquest, in 1997, as a newly-democratic South Africa held the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, looking into apartheid era atrocities, the officials involved maintained “that Biko had attacked one of their colleagues with a chair after he sat down without asking for permission,” according to the NPA. “In the ensuing scuffle to restrain him, Biko hit his head against the wall, they claimed.”

Authorized by then President Nelson Mandela and headed by Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was set up as a court-like body and offered amnesty to some of those who testified. It was widely seen as a model of restorative justice around the world, but more recently questions have been asked locally about whether justice was denied in favor of reconciliation.

Now, South Africans hope to finally get the truth about what’s widely considered to be Biko’s brutal torture and murder.

The reopening of Biko’s inquest comes after President Cyril Ramaphosa opened an inquiry in April looking into whether his predecessors in the African National Congress party had blocked prosecutions of apartheid crimes.

Another high-profile case currently being re-examined is that of a group of anti-apartheid activists known as “the Cradock Four.” They were abducted and murdered by security forces in 1989 but no one has ever been prosecuted for the killings.