Diet, exercise, sleep — all are fundamental to our health, but our relationship to light doesn’t get mentioned as much. Now, a massive new study suggests light-driven disruption can take years off our lives.

Scientists tracked nearly 90,000 people in the U.K. who spent a week with wrist-worn activity devices equipped with light sensors. Then, they analyzed their risk of dying over the next eight years. The results were published in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences.

The study participants with the brightest nights had a 21% to 34% higher risk of premature death, compared to those who were mostly in the dark between midnight and dawn.

The opposite was true for daytime.

People who enjoyed the brightest days had a 17% to 34% lower mortality risk than those who were in dim environments during the daytime.

The data underscore that light represents an “emerging risk factor for poor health and longevity,” says Daniel Windred, lead author of the study and a postdoctoral researcher at Flinders University in Australia.

Previous large-scale studies have found similar associations between mortality and light exposure, for example using satellite data and self-reports. However, the U.K study is the first to directly measure personal lighting environments around the clock.

“It’s a very powerful study,” says Dr. Charles Czeisler, chief of the Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

“We’re not talking about a marginal change. We’re talking about huge increases in risk associated with an easily modifiable risk factor,” he says.

While the study can only show a correlation — not prove causality — the “dose-dependent” response to light was evident even when the researchers controlled for factors like socioeconomic advantage, income and physical activity.

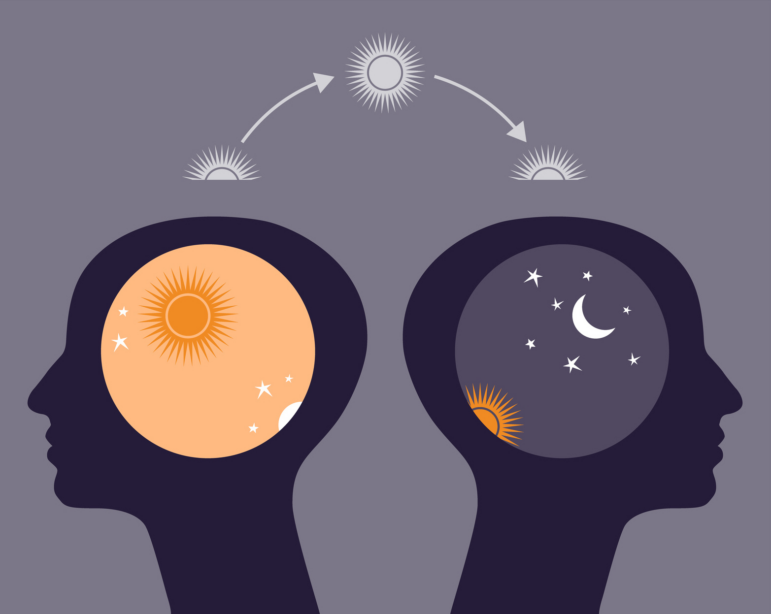

The results reflect decades of research indicating that our modern relationship to light can spell disaster for our circadian rhythms — the patterns in our physiology and behavior that fluctuate over the 24-hour cycle — influencing sleep, blood pressure, how we use energy, release hormones and countless other functions.

“We are flooding the nighttime with light that was never possible before and shielding ourselves from light during the day,” says Czeisler.

Here are four takeaways from the research.

Outside light is best

The benefits of having bright days were consistent from early in the morning to late in the afternoon.

Windred says it’s not hard to interpret the results: They represent people who were spending time outside in daylight.

“There’s a massive jump in the intensity between an indoor and an outdoor environment,” he says.

We’re talking orders of magnitude.

In a typical indoor environment, you may be exposed to about 100 to 500 lux (a unit of measurement for light), compared to anywhere from 10,000 to over 100,000 lux depending on the conditions and time of day. Even a cloudy day can be well over 1,000 lux.

The central circadian pacemaker in our brain is particularly sensitive to light in the morning, and prioritizing light at that time can make you more alert.

But even if you can’t pull that off, Windred says you will still reap the benefits of outdoor light later in the day. “If you come home from work in the afternoon and the sun is up, it’s still a good time to get light.”

In fact, Czeisler says people tend to underestimate the effects of being outside during dawn and dusk — times when you are being exposed to different wavelengths and intensities of light.

“We think that these transitions are probably particularly important,” he says. As long as there’s daylight though, he encourages people to get outdoors, ideally for at least half an hour to 45 minutes.

“It doesn’t have to be all at once,” he says, “This will do wonders for their health.”

Look for the contrasts

You can picture circadian rhythms as undulating currents, with the ups and downs reflecting your body’s changes throughout the dark-light cycle.

Digesting food, repairing organs, replenishing the energy in our brains and clearing out toxins, all of these function better if the circadian system resembles a robust wave.

And light is the most powerful cue. During the day, it can enhance our rhythms — and at night, suppress or shift their timing.

“The study is highlighting that you really need this contrast,” says Laura Fonken, a neuroscientist at the University of Texas at Austin, “It’s not just about having too little light during the day or too much light at night.”

Put another way: You don’t want your day and night lighting environments to be comparable. That can easily happen if you spend the bulk of your days in an office, without much natural lighting, she says.

In fact, the U.K data suggest the harms can add up if light is causing your circadian rhythms to be misaligned on both fronts.

“We estimate that people with both bright days and dark nights could be living up to five years longer than people with bright nights and dark days,” says Windred.

Light can be protective

Bright days can also set you up for a better evening — improving your sleep and shielding you against some of the downsides of artificial light at night.

“We know that exposure to broad daylight during the day can actually reduce the sensitivity of our circadian system to light exposure at night,” says Windred.

Studies measuring the effect of nighttime light on the hormone melatonin, which promotes sleep, support this concept: Study participants who spent their daytime in dimly lit conditions had much greater melatonin suppression when they encountered light at night. That’s compared to those who were exposed to more light during the day.

Czeisler says this doesn’t mean you will be completely impervious to the disruptive effects of light during the evening, especially the blue-enriched light that’s emitted from our devices.

“That sends a direct signal to the brain saying it’s daytime,” he says.

Czeisler’s lab has documented that reading from light-emitting tablets in the hours before you go to sleep can “shift your circadian rhythm, making it harder for you to fall asleep, more difficult for you to wake up and less likely that you’ll go to bed at an earlier hour the next day.”

Keep lights out in the dead of night

People who had the lowest chance of dying in the coming years were exposed to barely any light between about midnight and 6am, the study found.

On the other hand, bright light during the dead of night — specifically between 2:30 and 3am — was associated with the highest risk of mortality.

“That’s the most important time to avoid light,” he says, “It also happens to be the time that the circadian system is the most sensitive to light.”

In recent decades, scientists have linked light-driven disturbances to all manner of health problems — obesity, heart disease, diabetes, cancer, mental illness and other conditions. Scientists have even shown that misalignment of circadian rhythms over relatively short periods of time can mess with blood pressure and how the body handles glucose.

The hazards of working the night shift are well-documented, especially for cardiovascular and metabolic health.

In this latest study though, Czeisler points out even when shift workers were excluded from the analysis, the detrimental effects of bright light at 3 or 4 in the morning were still “highly significant.”

The best time to turn off the lights will depend, to some extent, on your schedule and chronotype — which is your body’s natural preferences toward being more of a morning or evening person — says Fonken. But the bottom line is simple: The stretch of time when you sleep should be as dark as you can make it.

This story was edited by Jane Greenhalgh

Transcript:

STEVE INSKEEP, HOST:

Here are some things that affect our health – diet, exercise, the amount of sleep we get. NPR’s Will Stone brings one more factor to light.

WILL STONE, BYLINE: Light is the most powerful cue for our circadian rhythms. These patterns in our biology fluctuate throughout the day, influencing our hormones, blood pressure, metabolism, when we fall asleep, and countless other functions. And for millennia, humans evolved with the natural dark-light cycle.

DANIEL WINDRED: It’s only very recently that we’ve actually been able to manipulate our lighting environments.

STONE: Daniel Windred is a postdoctoral researcher at Flinders University in Australia.

WINDRED: If we have bright nights and dark days, we’re actually altering the way our cells and tissues operate through our body.

STONE: A massive new study from Windred and his team suggests light-driven disruption can take years off our lives. They collected data from close to 90,000 people in the U.K, who each spent a week with a light-sensing device on their wrist. Their analysis shows exposure to light predicted the risk of dying over the next eight years.

WINDRED: We found that people exposed to the brightest nights had a 21-34% higher risk of premature mortality.

STONE: On the other hand, bright days were associated with lower mortality – as much as a 34% decreased risk for the top light-getters. Windred says this probably represents people who spend more time outside during daylight.

WINDRED: There’s, like, a massive jump in the intensity between an indoor and an outdoor light environment.

STONE: While the study can’t prove causality, the link between mortality and light was there even when controlling for factors like physical activity and income. Dr. Charles Czeisler is a longtime circadian researcher at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

CHARLES CZEISLER: I think that this is a very exciting milestone.

STONE: Reflecting decades of evidence, including carefully controlled lab experiments, showing that inappropriately timed light can be hazardous. It’s linked to mental illness, cancer, and especially metabolic and cardiovascular-driven diseases.

CZEISLER: We’re not talking about a marginal change in your risk of death, or your risk of heart disease or diabetes. We’re talking about huge increases in risk associated with an easily modifiable factor.

STONE: The study suggests getting bright light in the dead of night, specifically between 2 a.m. and 3 a.m., was the most harmful. But Czeisler’s lab and others have shown blue-enriched light – coming from a tablet or a smartphone – even before bedtime can disrupt your circadian rhythms. The good news is that daylight can help synchronize our rhythms and even be protective.

CZEISLER: Exposure to brighter light during the daytime makes us less sensitive to light at night.

STONE: The dangers of the night shift to health are well-documented. This U.K. study excluded shift workers, though, which makes it relevant to many more people. Laura Fonken, a neuroscientist at the University of Texas at Austin, says this study is a good reminder for those of us who spend our days in an office.

LAURA FONKEN: Where you’re in a cubicle where there’s no windows around, you’re also not getting normal daytime light levels. So then it’s really that your body can’t sense that contrast between night and day very well.

STONE: This suppresses the natural ups and downs of our circadian rhythms, which is also linked to higher mortality. The solution here is intuitive – as much as possible, shield yourself from light during the middle of the evening. And during the day, Dr. Czeisler advises people to get outside for at least 30-45 minutes.

CZEISLER: They will do wonders for their health.

STONE: It doesn’t have to be in broad daylight, either. A cloudy day, first thing in the morning or late afternoon – all of it can help keep our circadian rhythms on track. Will Stone, NPR News.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)