Ghanaian photojournalist Paul Ninson was thrilled — and surprised.

When he came to New York to study photography five years ago, he found a trove of images of life in Africa, past and present, in the archives of the city’s libraries, galleries and museums.

Here he was thousands of miles from Ghana surrounded by more visual history of Africa than he had ever seen back home.

That paradox led to an idea: create a library of photobooks in Ghana to bring the African story home, allowing people to learn about their history and give them the tools to tell new stories of the continent.

“A man does not know his true identity when he does not know his history and the background of where he comes from,” says Ninson. “And for us to solve problems in Africa, education is critical.”

This idea has been realized with the creation of the Dikan Center in Accra, Ghana’s capital. Dikan means “take the lead” in the Akan language, primarily spoken in southern Ghana and the Cote d’Ivoire. The library celebrated its second anniversary this past Monday.

Big dreams

This isn’t the only time Ninson set his sights on a seemingly impossible dream. When he initially pursued a career in photography, the challenge felt daunting. Photography isn’t exactly valued as a career path in Ghana, Ninson says: “If you tell your parents you’re going to be a photographer, it was like, ‘Yuck, what? Go be a lawyer.”’

But Ninson felt photography was his calling. He was deeply influenced by the rich family history of storytelling passed down through his grandparents and later, captivated by a friend’s images, developed a love of photography. It felt natural to combine the two arts, so he dove in.

He sold his iPhone, bought a camera and began studying photography, largely teaching himself.

Though Ninson began his journey with commercial photography, he soon shifted his focus to stories closer to his heart — those of African history and culture that he would capture as a budding photojournalist. His 2017 project, “Village With No Men,” offered an intimate look at the the village of Umoja in northern Kenya — a female-only community established by women who escaped gender-based violence and oppressive patriarchal environments in their former villages.

New York frame of mind

Ninson still sought a formal education in photojournalism. Unable to find a suitable program in Africa, he left Ghana in 2019 to study Documentary Practice and Visual Journalism at the International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York City. There, he devoured the center’s hundreds of photobooks. In Ghana, he only had access to five or six of such books.

As he ventured deeper into the city, he discovered more visual histories of Africa than he had experienced at home, such as documentation of Ghana’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah at the New York Public Library. The museums and libraries Ninson visited were unwilling to give him their archives to return to Africa, which led to his idea to create a library in Africa that held such stories.

Akin to coffee table books, photobooks are an ideal vehicle for stories since they are portable and can live on a shelf indefinitely. Michael Itkoff, co-founder of Daylight Books, an organization that showcases the work of documentary and conceptual photographers, has been publishing photobooks since 2010. A supporter of Ninson and the Dikan Center from the start, Itkoff says photobooks offer a different visual experience in today’s world, which is often focused on the volume and speed of images available online. “The photobook allows for an intimate and more slowed down — and I would say elegant — experience of visuals,” says Itkoff.

The great book hunt

With characteristic determination, Ninson began scouring New York City for books to ship to Ghana. While continuing his studies amid the COVID-19 pandemic, he searched secondhand stores on the Lower East Side, engaged in online bidding wars and reached out to publishers and galleries, some of whom donated hundreds of materials. He maxed out his credit cards and lined his apartment walls with books, using Uber and U-Haul trucks to transport the books to storage units he rented across the city.

He managed to amass more than 30,000 volumes — mainly about photography filmmaking, but also issues of publications like National Geographic dating back to the early 1940s.

Ninson had additional support from his friend and collaborator, Brandon Stanton, (creator of Humans of New York). Stanton started a GoFundMe that raised over $1.2 million for the founding of Dikan. With funding secured, Ninson was finally able to pack the collection for the ocean voyage from the Bronx (where his shipping agent was located) to Ghana.

In December 2022, the Dikan Center opened its doors just a few hundred yards from the Gulf of Guinea — and the same ocean waters that bore the ships of the Atlantic slave trade. In a former residence that was renovated to house the center, anyone is welcome to sit with the African story as long as they’d like.

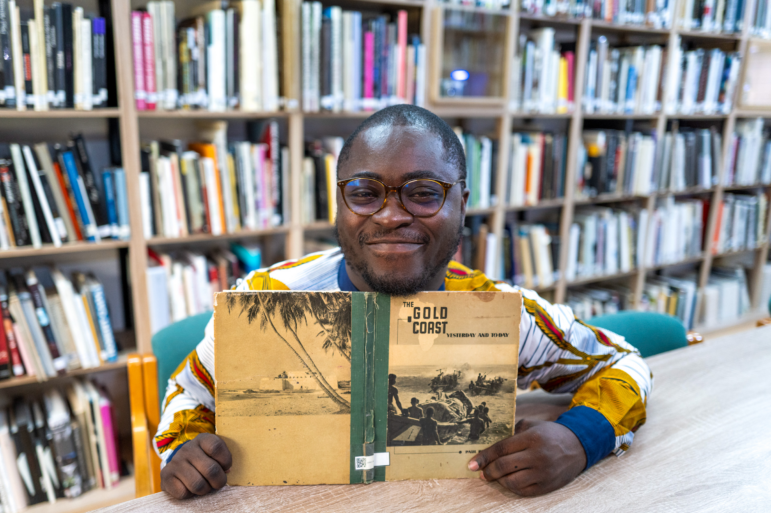

Dikan’s holdings are separated into two collections: one centered on African and African American stories, the other containing the work of photographers from around the world. Ninson’s favorite book is also Dikan’s oldest, and the first book he purchased in New York: The Gold Coast Yesterday and Today by Paul Redmayne, published in the early 1940s. The book contains images made when Ghana was still a colony known as the Gold Coast before gaining independence from the British in 1957. The narratives told from a colonial perspective of the country that would become Ninson’s homeland remain for him “a constant source of inspiration in my work at Dikan, reminding me of the rich heritage we carry and the stories that need to be shared with the world.”

George Koranteng is an Accra native and digital communications specialist with The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations in Ghana. Interested in photojournalism and documenting Ghanaian culture and history, Danso visits Dikan often, staying for hours at a time. Danso recalls that when he first Googled “photojournalist,” only white photographers appeared in the results. “And the question that I asked myself is ‘Are there not any Black photojournalists or documentary photographers?'” he says.

Through Dikan’s photobooks, Koranteng was able to spend meaningful time absorbing the work of Black photojournalists, such as the great Gordon Parks, an American photographer renowned for documenting the civil rights movement and Black America. Danso had known of Parks but sitting with the books allowed him to connect intimately with Parks’ methods and style, which fundamentally changed his art. “He [Parks] has a way of capturing powerful images of Black people. So for me, it actually changed the way I photograph. I really focus on what light can actually do to the skin of people, how light actually plays on the skin of Black people … when it comes to creating very powerful images…”

Storytelling lessons

To complement the books, Dikan provides educational workshops, fellowships and seminars on the skills associated with photojournalism and visual storytelling, providing a new generation of storytellers and creative leaders with the tools to tell new stories of the continent. Dikan’s efforts to train new storytellers has become impactful to the point that industry veterans are travelling to teach them. One of last year’s workshops; “Photojournalism: Crafting Visual Narratives,” was taught by Pete Souza, former chief official White House photographer during the Reagan and Obama administrations, and veteran photo editor Alice Gabriner (National Geographic, TIME Magazine, and The New York Times). The center’s flagship educational offering is a full-time program in documentary storytelling and visual journalism similar to the one Ninson completed at ICP. The inaugural class — eight students from Ghana and two from Nigeria — graduated last December.

Complementing the educational programs, Dikan helps mitigate the technological barrier to visual storytelling with access to the digital tools needed to tell new stories. The center houses a photo studio, and provides access to computers, digital cameras, (including 360-degree cameras), and virtual reality equipment.

Not all of Dikan’s stories live in books on its shelves. Dikan hosts rotating exhibitions and film screenings. The center’s current exhibition: “Tewahdo,” showcases female photographers Sehin Tewabe and Svenja Krüger’s documentation of the life and culture of Ethiopian Orthodox Christians.

Ghanaian Daniella Afful was particularly moved by Dikan’s second exhibition, “1957: Freedom and Justice,” which presented images of Ghana’s Independence from British Rule. Afful said it gave her a new perspective on this pivotal moment in her country’s history as well as a better understanding of day-to-day life at the time. “People actually went to bars. You see old-school dance moves being pictured on the wall … And I didn’t even know that there were actual, there were that many photographers in the past. I thought photography was something modern in Ghana…”

In Afful’s eyes, Dikan is a spark for the growth of Ghana’s creative community: “Dikan has magnified art, magnified photography. Dikan has kind of given us the hope that we may soon have a music library in Ghana. We could have a film library in Ghana — anything just to preserve our history and make history.”

Max Posner is a documentary photographer based in Richmond, Virginia. You can view his work at maxposner.com.