Scientists are updating their view of how drugs like Adderall and Ritalin help children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder stay on task.

The latest evidence is a study of thousands of brain scans of adolescents that confirms earlier hints that stimulant drugs have little direct impact on brain networks that control attention.

Instead, the drugs appear to activate networks involved in alertness and the anticipation of pleasure, scientists report in the journal Cell.

“We think it’s a combination of both arousal and reward, that kind of one-two punch, that really helps kids with ADHD when they take this medication,” says Dr. Benjamin Kay, a pediatric neurologist at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and the study’s lead author.

The results, along with those of smaller studies, support a “mindset shift about what stimulants are doing for people,” says Peter Manza, a neuroscientist at the University of Maryland who was not involved in the research.

The new research analyzed data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study, a federally funded effort that includes brain scans of nearly 12,000 children. About 4% of these kids had ADHD when they entered the study, and nearly half of those were on a prescription stimulant.

About 3.5 million children in the U.S. take an ADHD medication, and the number is rising.

Medication and brain networks

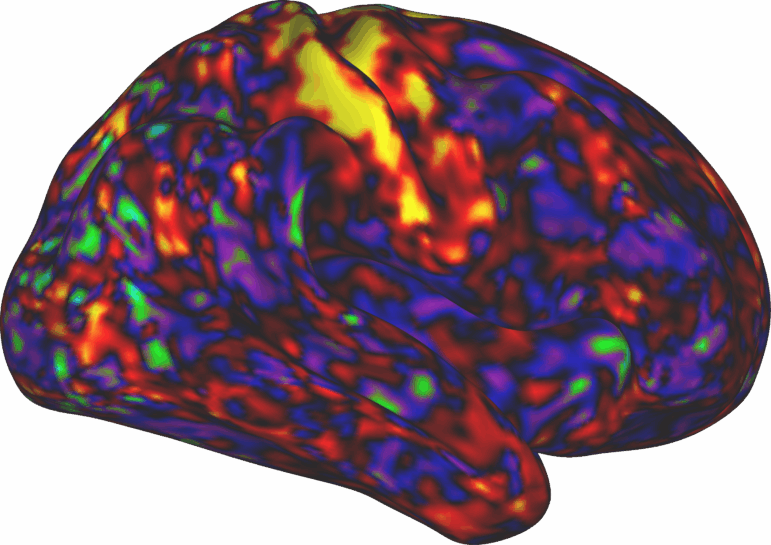

The brain scan data included a type of MRI that measures brain activity when a person is at rest. That allowed Kay and a team of scientists to see which brain areas were becoming more active in response to the drugs.

Kay expected to find lots of activity in areas that let a person control what they pay attention to.

“What I actually found was that those were the parts of the brain that were least affected,” he says.

Instead, the drugs were stimulating areas that help people stay awake and alert, and areas that anticipate a pleasurable reward.

This double effect seems to occur because stimulants like Ritalin and Adderall boost levels of two different brain chemicals, says Dr. Nico Dosenbach, the paper’s senior author and a professor at Washington University.

The first chemical is norepinephrine, which prepares the body and brain for action.

The study found that this “fight or flight” response counteracts the usual cognitive declines associated with sleep deprivation on cognitive performance. Lack of sleep is a problem for many adolescents, but especially those with ADHD.

The second brain chemical is dopamine, which plays an important role in the brain’s reward system. And a boost in dopamine levels may help children with ADHD feel more positive about mundane tasks like homework.

Usually, the brain’s expectation is, “this is going to be terrible, this is going to be boring,” Dosenbach says. “Dopamine can make you more tolerant because you are feeling a slight, low-level reward.”

It’s still too soon to know whether that’s what’s going on, Manza says. But he agrees that stimulants are doing something in the brain that helps kids with ADHD do things like homework.

“They don’t find math problems very interesting, but after a dose of Ritalin it might seem more interesting to them,” he says, “and so they’re willing to persist and finish the task.”

Brain scans before drugs?

The new study’s findings shouldn’t undermine clinicians’ confidence in the effectiveness of stimulants for ADHD, Kay says. But they do suggest that it’s important to rule out factors like sleep deprivation before turning to medication.

“This was a really personal paper for me because I prescribe these drugs all the time,” Kay says.

The results also suggest that brain scans might eventually offer a way to know whether a child is likely to benefit from drug treatment, Manza says.

“Stimulants don’t work for everyone,” he says, “so we need to better target the individuals who need them.”

MRI scans could even offer a better way to diagnose ADHD someday, Manza says. That’s badly needed, he says, in an era where more and more children and young adults are being told they have the disorder and should be on medication.

Transcript:

JUANA SUMMERS, HOST:

Scientists are changing their view of how drugs like Adderall and Ritalin help children with ADHD stay on task. NPR’s Jon Hamilton reports on a new study that found the drugs act on brain networks involved in alertness and reward but not attention.

JON HAMILTON, BYLINE: About 3.5 million children in the U.S. take stimulants for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD. Dr. Benjamin Kay, of Washington University in St. Louis, says he finds it puzzling that these drugs actually work.

BENJAMIN KAY: If we’re treating predominantly hyperactivity, why would a drug that wakes you up more help with that?

HAMILTON: So Kay, a pediatric neurologist, jumped at the chance to study how these stimulants affect a child’s brain.

KAY: This was a really personal paper for me because I prescribe these medications all the time.

HAMILTON: Kay was part of a team that reviewed data from a government study that includes brain scans of nearly 12,000 adolescents. About 4% had ADHD, and nearly half of those children were on a prescription stimulant. Kay says that allowed the team to see which brain areas were affected by the drugs.

KAY: What I expected to find was that the stimulants would act on the parts of the brain that modulate attention. What I actually found was that those were the parts of the brain that were least affected.

HAMILTON: Instead, the drugs stimulated brain areas that help us stay awake and alert. They also activated areas that anticipate a pleasurable reward.

KAY: We really think it’s a combination of both arousal and reward – that kind of one-two punch – that really, really helps kids with ADHD when they take this medication.

HAMILTON: The first punch involves norepinephrine, which prepares the body and brain for action. The study found that this response could counteract the effects of sleep deprivation, a common problem in children with ADHD. Dr. Nico Dosenbach, a coauthor of the study, says the second punch seems to help kids overcome another common problem.

NICO DOSENBACH: They’re looking at some kind of homework and their brain goes, this is going to be terrible. This is going to be boring. I don’t like this, and then you can’t stick with it.

HAMILTON: Dosenbach says ADHD drugs seem to limit this negative response by boosting levels of dopamine, a brain chemical that influences motivation and pleasure.

DOSENBACH: It can make you more tolerant because you’re feeling a slight sort of low-level, low-key reward.

HAMILTON: Dosenbach says dopamine may also explain why children with ADHD can sit still and focus on an activity that they do find rewarding. He says this behavior even led one dad to conclude that his son was faking ADHD.

DOSENBACH: He was like, well, when I take him hunting, he can sit in a high stand all day long without moving a muscle. But in school, he’s bouncing off the walls and leaving the classroom and wandering off the premises.

HAMILTON: Dosenbach suspects hunting simply produced enough dopamine to offset the boy’s hyperactivity. The findings appear in the journal, Cell. Neuroscientist Peter Manza, of the University of Maryland, says they show how ADHD researchers are moving away from the idea that stimulants directly improve attention. He says his own work suggests that stimulants are boosting motivation in kids with ADHD.

PETER MANZA: They don’t find math problems very interesting, but after a dose of Ritalin it might seem more interesting to them, and so they’re willing to persist and finish the task.

HAMILTON: Manza says the study also suggests that brain scans might eventually offer a way to confirm that a child has ADHD and will benefit from drug treatment.

MANZA: Stimulants don’t work for everyone, and so we need to better target the individuals who need them and not unnecessarily prescribe them to the individuals who don’t need them.

HAMILTON: That’s a growing concern as stimulant prescriptions continue to rise.

Jon Hamilton, NPR News.

(SOUNDBITE OF DELICATE STEVE’S “PEACHES”)