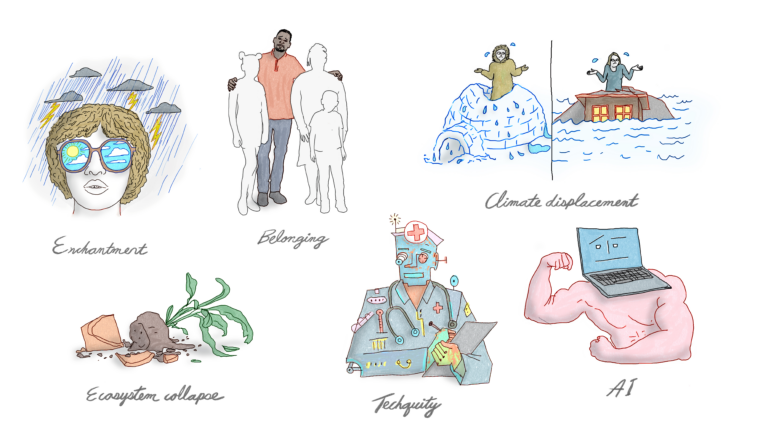

If you’re concerned about ecosystem collapse and climate displacement, you might look to a One Health approach for possible solutions. Techquity could provide a roadmap for countering any of the potential ills that AI may bring, despite all the good that its disciples promise. And if the troubles on our planet have you feeling unmoored, try seeking out belonging and even some enchantment.

These are the buzzwords that global health and development experts say we’ll hear more of in 2025 — a vocab mix of pending global catastrophe and possible remedy.

Belonging

It’s something of a paradox. Our planet is filled with a dizzying number of humans (8 billion and counting), many of whom are connected to one another electronically. And yet more and more people are lonely. Dr. Vivek Murthy, the current U.S. Surgeon General, has spoken of an epidemic of loneliness and isolation..

“Loneliness is far more than just a bad feeling,” he wrote in an advisory in 2023. “It harms both individual and societal health. It is associated with a greater risk of cardiovascular disease, dementia, stroke, depression, anxiety and premature death.” Loneliness is a global concern, as evidenced by the World Health Organization creating an international commission to address it as a public health crisis in late 2023.

Murthy invites us to “build a movement to mend the social fabric” by deeply listening, sharing a meal or volunteering. “The keys to human connection are simple but extraordinarily powerful.”

In Kenya, Sitawa Wafula, an independent mental health advocate, has developed her own approach. She launched and ran a support line that connected more than 11,000 people with mental health resources in its first year. “Many users shared that simply being heard by someone who understood their struggles created an immediate sense of connection,” Wafula says.

That’s why she believes that belonging will be a global buzzword this year. “For those facing stigma and alienation,” says Wafula, “belonging acted as a protective factor, encouraging them to seek further support and adopt healthier coping mechanisms.”

Wafula has also facilitated storytelling workshops among those in the African diaspora, many of whom face challenges surrounding identity and disconnection in their new homes. “Through sharing and affirming each other’s experiences,” she says, “they developed a shared sense of belonging that not only reduced isolation but also fostered resilience.”

Climate displacement

Moumouni Kinda, the CEO of the NGO Alliance for International Medical Action (ALIMA), points to climate displacement as “a defining challenge of our time.”

For instance, ferocious flooding in recent years has surged in Africa, Asia, Europe and North and South America. “In Nigeria, severe floods swept through 29 of the country’s 36 states, and more than 225,000 have been displaced,” says Kinda, “many of whom had already been uprooted by conflict and climate change.”

Those who are displaced — known as climate refugees — tend to lack basic services such as medical care, clean water and sanitation, which Kinda says can fuel outbreaks of disease and further deepen inequality.

“We will see more climate displacement next year as climate pressures escalate,” he says, “and the scale and urgency of these crises continue to grow. By 2050, climate change is likely to force 216 million people to migrate within their own countries, including 86 million in sub-Saharan Africa.”

Techquity

Maymunah Yusuf Kadiri, a neuro-psychiatrist at Pinnacle Medical Services in Lagos, Nigeria, describes what keeps her and her colleagues awake at night.

First, only about 1 in 10 Nigerians have health insurance. Over 70% must pay for medical care out of pocket.

Second, Kadiri says that a quarter of the population of Nigeria wrestles with mental health issues. But there are fewer than 250 practicing psychiatrists in the country of 223 million, however — in part due to a massive exodus of health care professionals in the wake of the pandemic. The result: Most people cannot get the mental health support they need.

“Stigma, lack of accessibility and high costs prevent millions from seeking help,” she says.

Kadiri says the solution to these problems is technology, which a variety of startups in Nigeria are championing. Technological solutions can reduce costs, illness and mortality. She points to telemedicine, which is making “health care accessible, affordable and available,” she says.

To describe this blend of equity and technology to bring health services and innovations to everyone — especially underserved communities and those with limited resources, Kadiri uses a word that’s bubbled up in the past few years: techquity.

As digital health services like wearables (e.g., fitbits and smart watches) and virtual at-home care continue to grow in popularity, “the risk of marginalized populations falling behind will only increase,” says Kadiri. “By creating technology that is accessible, inexpensive and sensitive to socioeconomic and cultural hurdles, techquity will help close that gap and ensure that everyone benefits.”

She acknowledges that financing and infrastructure remain as hurdles. Her practice has equipped the mobile mental health counseling booths they’re using with solar panels to reach low-resource communities without electricity.

It’s inevitable that health care delivery will become increasingly digital. Junaid Nabi, a senior fellow at The Aspen Institute, says one result will be “the development of personalized care ecosystems and improved efficiency.” Investing in techquity will help ensure that such advances can benefit everyone.

Ecosystem collapse

Last month, when Cornell University disease ecologist Raina Plowright was visiting Canberra in southeastern Australia, she learned that the numbers of migratory Bogong moths have declined substantially.

“These moths — as large as my hand — used to gather in the millions when I was a child,” she says, “navigating by the stars of the Milky Way to migrate between northern and southern states of eastern Australia. They were a spectacular site, and many animals depended on them [for food], like the now endangered pygmy possum.”

But Plowright says the combination of drought and land clearing have caused the population of moths to crash. In late 2021, the species was added to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. And with many fewer moths, the pygmy possum’s future is even bleaker.

Taken together, this is just one example of an ecosystem collapse. Remove species after species from a place, and eventually the entire ecosystem caves in. It’s increasingly common.

Elsewhere in Australia, koalas are in rough shape. “When I was a kid,” Plowright says, “I used to count koalas along a five-mile stretch of road in the Victorian Grampians and regularly spotted 30 or more. Now, I hear the koalas have disappeared from the Grampians. My wildlife veterinary colleagues working with koalas in other parts of Victoria tell me that the koalas they assess in the wild are often diseased and emaciated.”

In addition to the precipitous loss in biodiversity, ecosystem collapse brings a severe threat — disease. “Viruses that have long existed in nature, separate from humans, will find new pathways to us,” warns Plowright.

For instance, the same factors that tanked the number of Bogong moths have also driven “the collapse of the giant bat migrations that have led to Hendra virus spillover,” says Plowright. That is, when bats have less food due to habitat loss or climate change, “they just don’t have enough energy to maintain an immune response to keep these viruses in check.”

This means that one way of keeping ourselves safe from zoonotic diseases is to invest in protecting ecosystems and the species they contain.

AI

Artificial Intelligence (AI) isn’t a new term — by all accounts, its origins date to a workshop in the 1950s.

But it’s clear that this buzzword will be ever more present as it hits the age of 70, especially as it’s increasingly offered up as a cure-all in the global health arena.

It has the potential to “provide insights into the causes of disease,” says W. Ian Lipkin, an epidemiologist at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, “inform the design of drugs and vaccines to mitigate morbidity and mortality of infectious diseases, autoimmune disorders and some cancers, provide new ways to enhance communication and provide the tools needed to differentiate facts and alternative facts.”

Iqbal Dhaliwal, the global executive director of the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab at MIT, also believes that AI can create positive social impact. “It is in reach of anyone with a smartphone,” he says, “has low marginal cost of implementation and is constantly improving.”

But he cautions that the social sector is filled with examples of technologies “touted as silver bullets that fell short of expectations, like laptops for school children and clean cookstoves.” Dhaliwal argues that we must maximize the good that AI can do while minimizing its harm. (The laptop idea tanked because providing hardware without additional training and software doesn’t tend to improve academic performance. And clean cookstoves flopped because “households didn’t use them consistently or maintain them properly, and were reluctant to abandon their traditional stoves,” says Dhaliwal.)

He points to insights gathered from years of assessing other technological interventions to guide us, but he stresses that ongoing evaluation is needed.

“As this technical revolution unfolds in real time,” says Dhaliwal, “we have a responsibility to rigorously study how these technologies can help or harm people’s well-being, particularly people who experience poverty, and scale only the most effective AI solutions.”

Lipkin says that AI is “an under- and overrated boon, threat and solution for every field from the arts to weather prediction.” But in the long run, he still views it as a force for good in the fields of medicine and public health.

Enchantment

“What skills will we need in the future?”

That’s a question that Edgard Gouveia Jr. of Brazil hears from people of all backgrounds. He’s the co-founder of Livelab, a non-profit that uses games and narrative to create an environment of “trust and empathy” to mobilize crowds to solve local problems.

His answer: storytellers — “people that are able to enchant society,” Gouveia says.

“In the moments of darkness, war and climate change, I think society [is] gonna need people that are able to see the hard reality with different, positive eyes — building hope, building caring, building connection.”

Gouveia says the most powerful storytelling finds light in the darkness and is capable of awakening our emotions and our senses. He points to Italo Calvino’s novel about an Emperor’s travels entitled Invisible Cities and Charles Eisenstein’s book The More Beautiful World Our Hearts Know Is Possible.

Despite its mixed reviews, Gouveia says the 1997 Italian film La vita è bella (Life Is Beautiful) is another good example. In the movie, a Jewish bookstore owner uses his wit and humor to hide the terrible reality of a Nazi concentration camp from his son.

Gouveia is hopeful that in a world increasingly beset with trouble, more of us can find wonder — and enchantment — in the challenge.

One Health

For a long time, human health, animal health and environmental health were considered as distinct domains with each one operating independently of the others. But Neil Vora, a senior adviser at Conservation International, says that approach “fails to capture the breadth of what’s really going on.”

He points to birds that — stressed from dwindling resources or disrupted habitat — migrate to new places, potentially spreading a strain of avian flu. He considers an extended wildfire season in Canada that cast plumes of smoke into the air, triggering asthma attacks and other respiratory problems along the Eastern Seaboard. This interconnection and interdependence of human, animal and environmental health are captured by the term One Health.

It’s not clear who coined the expression but Vora says one of the earliest references is from an interview with veterinarian William Karesh in 2003. Veterinary epidemiologists Calvin Schwabe and Jakob Zinsstag also contributed to the field early on.

“One Health is a concept Indigenous peoples and local communities have implicitly understood for generations,” says Vora. “That we are not apart from nature but rather a part of it. But it’s just now entering the vernacular of mainstream decision makers, at universities, major health institutions and the U.N. biodiversity conference, where nearly 200 countries agreed that biodiversity is a key determinant of health.”

The signs of a planet in crisis are evident — extinctions, epidemics, droughts and floods. “The term One Health is gaining traction,” says Vora, “because it distills these mounting phenomena that we all feel into a single human imperative: Only by mending our fractured relationship with nature can humanity halt climate change, biodiversity loss and the overlapping health crises that increasingly afflict us.”

Callout

Readers, if you have additional buzzwords you’d like to share, send the term and a brief explanation to goatsandsoda@npr.org with “buzzwords” in the subject line. We may include your submission in a follow-up post.