A bombing in 1998 at a Birmingham clinic that performed abortions captured the country’s attention, especially after it was determined to be the work of a serial bomber. Eric Robert Rudolph had previously placed three bombs in the Atlanta area, one at Centennial Olympic Park during the 1996 Games.

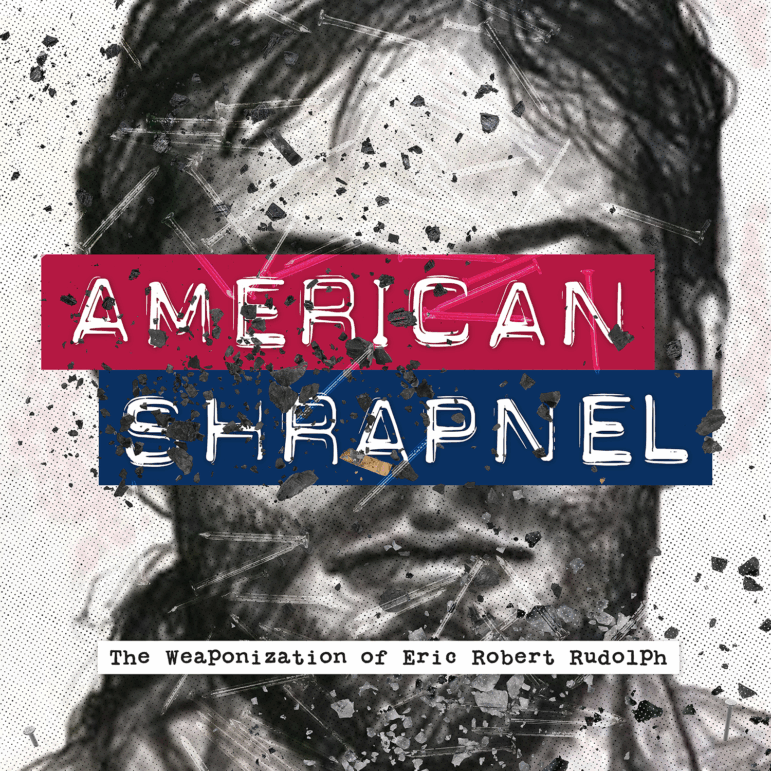

A new podcast called American Shrapnel from AL.com columnist and two-time Pulitzer Prize winner John Archibald captures the drama of what became a five-year manhunt for Rudolph. It explores how Rudolph’s brand of white nationalism is even bigger today.

The following conversation has been edited for clarity.

Following the bombing at the New Woman, All Women Health Care Clinic here in Birmingham, what was the mood in the city at the time?

It was wild. I mean, it was January ’98, and it blew up that morning. It was crazy, and feeling, atmosphere-wise, that particular day, it was chaos. The size of the reaction to it is hard to imagine today, because satellite trucks were everywhere, and the entire country had decided that this was somebody worth pursuing.

Tell us about the UAB student who helped break this case open.

His name is Jermaine Hughes, and he’s never wanted publicity. He’s never really talked about it. And we found some amazing tape of his interviews with the police that sort of tell the story. But he was at Rast Hall doing his laundry in the morning, and the bomb went off just up the street. And he looked up, and he saw a lot of people running toward the blast, the smoke. And he saw this one guy walking away. And you know, this kid dropped everything and said, this just doesn’t look right. And he followed him. And he saw this guy going behind buildings and putting on a wig and taking off a wig and changing clothes. And because Jermaine Hughes, this UAB student, dared to just drop everything and track this guy down and was very persistent about it, it probably saved a bunch of lives.

And it took another five years to capture Rudolph. Tell us about that.

He had stored a lot of food and had made some plans. He was a great sort of outdoorsman, people claimed, which is one of the great ironies of the story, because it plays out and he’s ultimately caught by this rookie cop in Murphy, North Carolina while diving in a dumpster for rotten bananas. And he had clearly not been in the woods this whole time, and had been sort of living close to Murphy and eating fast food at times and things like that. So, it’s pretty remarkable and full of irony.

You mentioned in the podcast that there is this through line of white Christian nationalism, militarism, call it whatever, experienced through Rudolph’s actions, up to our current era. And now you say it’s somewhat normalized. Any thoughts on why?

That sort of anger just has seemed to become manifest in today’s world, where so many more people are, you know, you look around now, you got Minnesota assassinations, you’ve got arson at the [Pennsylvania] governor’s mansion. You have all these things, all the time, and we don’t even register them anymore because it happens so often. The rhetoric of Eric Rudolph is that, you know, it doesn’t matter what the issue is. It’s us against them. And so we have so much of that in politics right now, it seems really sort of apropos to what he was standing for.

Yeah, and the internet probably helps fuel that fire a little bit?

When Eric Rudolph was being radicalized … that happened in a lot of ways. I mean, he grew up as a Holocaust denier, and he’d call himself ‘Adolf Rudolph’ and went to spend time with this Missouri extremist preacher, [this] anti-Semitic guy who had a big influence on him. To sort of be radicalized in that notion, you went to meetings or you ordered magazines from somebody who’d send them to you in plain brown envelopes, [send] books on how to build detonators, and that sort of thing. And today, it’s just so much easier, because this sort of language of not just hate, but resentment. It’s easier to get to on the web and on the dark web. You know, even on cable TV, these days. So, it’s just so much easier to find community that rallies around the anger and the call for violence. You know, 25 years ago, the kind of rhetoric that we hear today would be widely condemned on both sides of the aisle. It’s inflammatory, and it’s dangerous, and we think this is a good example of why.

In putting together American Shrapnel, John Archibald worked with Becca Andrews, a writer and professor, and John Hammontree, head of podcasting for AL.com. You can hear American Shrapnel wherever you get your podcasts. You can also learn more here.