This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, independent news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. It is republished with permission. Sign up for their newsletter here.

By Lee Hedgepeth, Inside Climate News

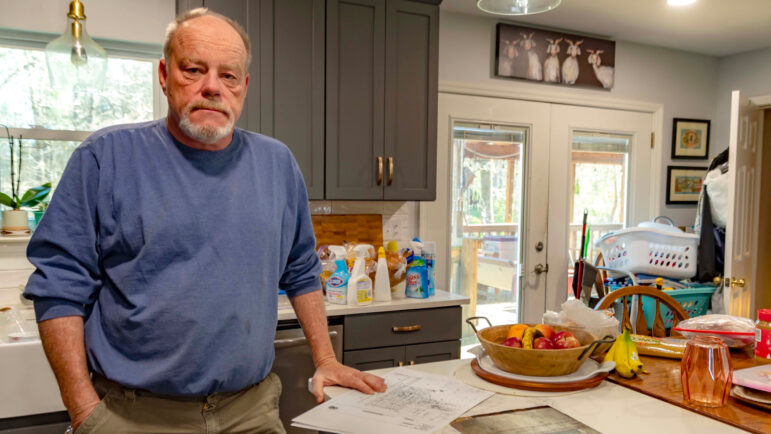

ADGER, Ala.—Charlie Utterback and his family live on top of longwall mining panel number 53.

Above ground, Utterback’s dogs welcome visitors with a bark and the wag of a tail. They guard, but mostly just lounge around the Utterback home he and his wife built on family land around 25 years ago.

Below ground, it will soon be much less peaceful. There, before the end of 2025, heavy machinery is scheduled to begin shearing off slices of coal along an expanse that, once work is complete, will leave an underground cavern well over a mile long and more than a thousand feet wide. If the Utterbacks are lucky, the only impact on their property may be minor structural damage caused by subsidence, or the sinking of land, a common occurrence at properties above such mining operations. But it’s being unlucky that the Utterbacks worry about.

In early March, a little over a mile away from the Utterback’s place, W.M. Griffice, 74, and his grandson Anthony Hill, 21, were resting in their home when the small house exploded, leaving little but the charred Alabama clay in its footprint. Both Griffice and Hill were transported to a Birmingham hospital in critical condition, authorities said. On Wednesday, Griffice died from his injuries, according to a family lawyer.

In the wake of the explosion, an Inside Climate News investigation confirmed that the Griffice home was located above proposed longwall mine panel 52, operated by Crimson Oak Grove Resources, LLC. Newly obtained regulatory maps confirm that mining was scheduled to reach the area beneath the Griffice home in February, just days before the explosion occurred. In a lawsuit, the family has alleged that Oak Grove Mine, its parent company, and a contractor are responsible for the explosion and, ultimately, for Griffice’s death.

Following the explosion, residents like Utterback are seeking answers about the mine and its activities, which have also led to the closure of a local park and left gas stations unable to sell fuel.

“They have destroyed our community,” Utterback said of those operating the mine. “And there’s no one to answer for it.”

Oak Grove Mine officials did not respond to multiple requests for comment, and has not yet responded to the lawsuit filed against it. And while federal mine regulators have been quietly citing the mine for various safety violations in the weeks since the Adger explosion that leveled the Griffice home, Alabama officials have done little to act, with state fire investigators still not responding to media inquiries related to the incident.

Utterback said mine officials have left homeowners in the dark, too. When he received a notice that mining would occur under his home, he called the number listed at the bottom for Crimson Oak Grove Resources to ask questions and express his concerns.

“The man who answered said, ‘I no longer work for them,’” Utterback said. So his questions and concerns, Utterback said, remain unaddressed.

A Southern grandfather remembered

Griffice was a typical Southern grandpa, his granddaughter said in a March interview, at one time even working as a coal miner. Kenzie Hill had been raised by Griffice and his late wife alongside her brother Anthony.

She wasn’t at the house when it exploded, but heard the thunderous sound from nearby. Griffice, Hill told ICN, had predicted his own fate, saying he believed his house might explode after hearing booming sounds he believed to come from the mine over and over in the months before the tragedy.

“He enjoyed hunting, fishing, and his dogs,” Griffice’s obituary said. “He retired as a construction worker and equipment operator. He loved his family and friends.”

The family’s lawsuit alleges that negligence on the part of the mining operator led to the explosion. In an amended complaint filed Tuesday, lawyers for the family named an additional defendant—Langley Dirt Works—claiming that at the behest of Oak Grove, company workers capped a water well on the Griffice property after the presence of methane was confirmed, leading to an increase in the risk of an explosion. Efforts to reach representatives of Langley Dirt Works were unsuccessful.

Federal fines, state indifference

So far, there has been little evidence that Alabama officials are moving to act decisively in the face of the March explosion or even formally determine whether the March explosion was caused by mine operations.

State fire marshals, who are typically charged with investigating similar tragedies, have not responded to requests for comment on the case. Kathy Love, director of the Alabama Surface Mining Commission, said her agency and others are “researching this devastating event,” but did not provide details about any formal investigation.

“We, as well as all other agencies are saddened and very much concerned over this tragic event,” she said in response to questions. “All agencies want to determine as best as possible the underlying cause.”

In a later interview with ICN, Love expressed skepticism that the explosion could have been caused by mining activity given the depth at which shearing takes place, but said her opinion was based on her experience, not on any particular information about the Oak Grove tragedy.

Love worked in a public accounting firm auditing coal mines before she transitioned into a role at the state regulatory agency, she said. In the decades she’s been involved in roles related to the mining industry, Love said she’d never heard of an above-ground explosion like this one.

“So it just blows my mind,” Love said. “It’s very unusual.”

Love said only three formal complaints have been filed against the mine in the last ten years but would not provide copies of those complaints, citing privacy concerns related to property owners’ personal information. All three complaints, Love said, were related to damage from subsidence potentially caused by the Oak Grove Mine.

Meanwhile, federal officials have been more active in regulating the activities of the mine, though regulators with the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) have not ordered the mine to halt operations.

In the years leading up to the March 8 explosion, MSHA records show that the agency cited Oak Grove’s operators at least 160 times for “significant or substantial” violations of federal safety regulations, meaning there was, in each case, “a reasonable likelihood the hazard…[would] result in an injury or illness of a reasonably serious nature.”

In 2015, mine workers at the site were evacuated by federal officials after a dangerous buildup of methane gas inside the mine. An online record of reported accidents at the mine shows five incidents in which it was cited for “ignition” of gas or dust since August 2022.

Federal regulators have also been busy in the wake of the March explosion. Since March 8, MSHA has cited Oak Grove for 107 violations, 40 of which were considered “significant or substantial.” The violations involved issues from miner training and safety to fire suppression and the “accumulation of combustible materials” inside the mine.

While Oak Grove hasn’t yet responded to questions about the Griffice home explosion, the mine’s lawyers have been busy in federal court, appealing the forced reinstatement of a miner who’d allegedly complained about safety issues before being dismissed by Oak Grove. In that suit, lawyers for Oak Grove argue that the Federal Mine Safety and Health Review Commission rules “did not provide operators…with due process.”

A community undermined and uninformed

While Oak Grove’s lawyers are challenging the legality of federal regulation around mine safety, Charlie Utterback just wishes representatives of the mine would answer his and others’ questions about what is happening in—and under—their community.

One March evening, a few weeks after the explosion, Utterback showed Inside Climate News the low-resolution map neighbors have been sharing amongst themselves, desperate for more details in what seems like an information vacuum.

The map, likely obtained from state regulatory records, had been re-copied again and again, passed from one resident to another like a treasure map. Asked where he believed the map ultimately came from, Utterback looked up grimly.

“I think it was smuggled out of the mine,” he said.

Maps showing the underground portions of Oak Grove Mine and other mines across Alabama aren’t readily available online. Instead, such records are kept in filing cabinets at the office of the Alabama Surface Mining Commission in Jasper, Alabama, located on the second floor of a bank more than an hour’s drive from Adger and the Oak Grove Mine.

Utterback said mine maps should be posted in a public place in town where citizens can easily see what’s located underneath their own property.

The above map was produced using various maps obtained from the surface mining commission‘s public records library in Jasper. It shows the extent of Oak Grove’s proposed mining under the community. Areas shaded beige indicated so-called “development mining,” areas used to access or support the surrounding mined caverns. The areas shaded green indicate planned longwall mining.

“Do you see how close they’re going to the school?” Utterback asked as he pointed at the map. Various points of interest on the map are shaded green—the park, closed since July 2023, for example, where kids used to play football and practice cheerleading.

“They even shut the church down for a year,” Utterback said.

All the while, there has been no coverage from local media about what’s happening in Adger, a reality compounded by the mine’s unwillingness to be transparent about its operations. In the end, Utterback said, there’s little he can individually do to stop Oak Grove from mining underneath his home. He does believe, though, that he should be able to look someone who represents the mine in the eye and hear directly from them about what they feel are the mine’s obligations to the community.

“Even a little more information would help things tremendously,” Utterback said. “Just so we actually know.”