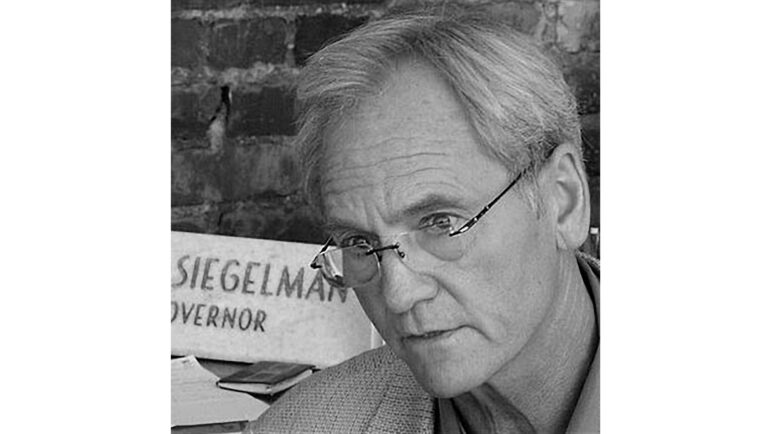

Former Alabama Gov. Don Siegelman said he’s haunted by memories of people he allowed to be put to death by the state. He specifically remembered the case of Freddie Wright.

An all-white jury convicted Wright, a Black man, of murdering two people in 1977. According to news reports, prosecutors suppressed evidence and Wright’s attorney was later disbarred. Wright was put to death in 2000.

“I had a chance to commute Freddie Lee Wright’s sentence,” Siegelman said. “I didn’t have the information available to me, because it was withheld by the prosecutors. He would not have been executed had I known what I know today.”

In addition to what he learned about capital punishment cases, Siegelman said his own experience as a federal defendant convinced him that the system is flawed. He said in that case, prosecutors acted improperly, leading to his conviction in 2006 on federal bribery and related charges.

Siegelman’s conviction attracted national attention, when in 2015, more than 100 former attorneys’ general submitted briefs on the former governor’s behalf. However, appeals courts rejected claims that the case was tainted by politics, and the U.S. Supreme Court refused a request to review his conviction.

Siegelman has since become an advocate for death penalty reform. With another former governor, Dr. Robert Bentley, Siegelman recently wrote an op-ed in The Washington Post that explained their regrets and called for changes to Alabama’s approach to the death penalty.

Siegelman recently sat down with WBHM’s Richard Banks.

The following interview was edited for clarity.

Explain your concerns about Alabama’s approach to capital punishment.

Alabama has two anomalies in our death penalty laws that that should shake the consciences of everyone. One is the fact that we have 115 people on death row who were sentenced to death after the jury was divided. It was not a unanimous jury. And we have 31 people on Alabama’s death row who are there because of what’s called judicial override, which is now an outlawed and banned practice in the state of Alabama. [* Note 1]

Prosecutors in the U.S. are immune from civil liability. Also, grand jury proceedings are secret. So, in your opinion, how does that affect death penalty cases?

Well, it should again shock everyone’s conscience that, because of this 1976 ruling by the Supreme Court [* Note 2], prosecutors have absolute immunity from civil liability for presenting false evidence, false testimony, or withholding exculpatory evidence to get an indictment or conviction. Prosecutors since the 1970s, since 1976, have been getting 99% of the indictments they seek [* Note 3]. That’s explainable when they can present false evidence, false testimony, in the secrecy of a grand jury, where there’s no lawyer or no judge present to rein in a runaway prosecutor who is presenting false evidence.

Why take up this issue now? What’s changed? Was there a moment when when it clicked?

Yeah, there was a moment when it clicked. It was when I was convicted of something that had only been contrived in the minds of the people who were prosecuting me.

And that was when, in 2006, you were convicted on federal bribery charges?

Yes, it was 2006.

So when that happened, it sort of shined a light on what could happen to other people as well.

When I heard the word guilty, I realized that the system was flawed and, at that moment, I thought about the people whose death sentences I set as attorney general, and I thought about the people who came before me and asked for clemency while I was governor. And if in everything there is a purpose or if in every situation one should find a purpose, it was as if God was telling me, okay, Governor, you’ve seen what’s wrong. Now go fix it.

How do you feel about capital punishment generally?

Well, I think that generally, we should leave death to God and not man’s whim. I think that, because we know that errors are occurring on death row, that we need — even if you believe in capital punishment, even if you believe that capital punishment can deter some future crime, the fact that we have it on the books might prevent somebody from committing a horrible act — you want to at least make sure that if we execute someone, we execute the person who actually committed the murder. And the fact is, I know from personal experience, from looking back on those people who came before me as governor — when I had a chance to commute Freddie Lee Wright’s sentence, I didn’t have the information available to me, because it was withheld by the prosecutors. He would not have been executed had I known what I know today, 23 years later.

Note 1

Under current Alabama law, capital murder cases include two steps involving jury decisions. First, it takes a unanimous jury for a guilty verdict. However, in the second step – the penalty phase – a jury can impose the death penalty with as few as 10 of 12 jurors voting for the death sentence. According to WUSF, an NPR affiliate in Tampa, only three states out of the 27 that impose the death penalty do not require unanimity when juries decide on death penalties in capital cases.

Also, current Alabama law prohibits judges from imposing the death sentence, after juries had instead opted for life in prison for those convicted of a capital crime. However, that law, passed in 2017, was not retroactive, leaving those persons sentenced to death by judicial override on death row. Alabama had been the only state to allow a judge to override a jury’s recommendation.

Note 2

See the following description of the ruling that applies to this case, Imbler v. Pachtman.

Note 3

This 2014 article in the Washington Post does show that for a one-year period from 2009 to 2010 that federal grand juries returned indictments 99 percent of the time. Siegleman referenced the following law blog.