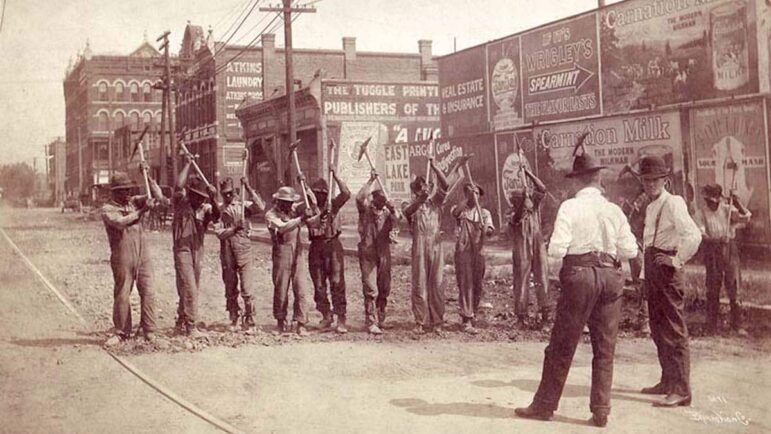

A century ago Alabama was among the states that made heavy use of convict leasing. Under this system, the state leased prisoners to businesses as laborers, particularly in coal mines. Many Black men were arrested on minor or false charges to keep that stream of cheap labor flowing.

The investigative public radio show Reveal took a look at U.S. Steel’s involvement in that system and argue the company has never fully reckoned with its past. Associated Press reporter Robin McDowell took part in the investigation.

What did you find with U.S. Steel in relationship to convict leasing?

We were looking primarily at Tennessee Coal and Iron and what happened when they moved their headquarters to Birmingham and when they were taken over by U.S. Steel. U.S. Steel continued to use prisoners for the next full five years. What we discovered, really, was that U.S. Steel has never been transparent about their role in convict leasing. They really have created their own narrative.

These years that U.S. Steel was using convict labor, this was around 1910?

U.S. Steel took over from TCI in 1907, and they continued to use prisoners for the next five years.

When U.S. Steel looked to its own history, how did it characterize this time period?

I think it’s important to remember who U.S. Steel was at that time. It was a company that was one of the biggest, if not the biggest, companies in the world, and it really helped build the nation. In 1960, they put out a promotional film that talked about their early days and really glorified the role they had in building up the South and neglecting to talk about things like convict leasing or the men who died. It was really focused on kind of the glory days or the role that they had in rebuilding the South after the Civil War.

Fast forward to today. As part of your reporting, you traveled to Birmingham, the Pratt City community. What did you find there?

One of the questions that we put to U.S. Steel was about the burial ground that was right on the site actually of the old Pratt mines. And we wanted to know, did they still own that property? And did they have records of the men who died there? So one of the things we wanted to do was go and look at this site, which is in a rather densely forested area in Pratt City. There’s no way to find it. There are no markers, there are no pathways. There’s not a fence, there’s not a sign. And so we went to Jack Bergstresser, who basically stumbled across this cemetery in 1994 while he was doing mapping of the coal mining operations for the U.S. government. And he brought us back to the site and it’s just basically being swallowed up by nature.

What response did you get from U.S. Steel to your reporting? I’m thinking of particularly, have attitudes changed since the 1960s?

It’s hard to talk about U.S. Steel’s role in Alabama without referring to Doug Blackmon and his reporting for The Wall Street Journal and also his book Slavery by Another Name. And after Doug Blackmon came out with his article and book, they put out a statement distancing themselves from the practice, saying “yes, they engaged in it, but it was something they had inherited from Tennessee Coal and Iron” … really kind of saying we were just doing what was done at that time.

There are other places in the South that are putting up memorials or plaques or acknowledging the use of convict labor. Was U.S. Steel going to reconsider or have a more honest look at its history? Eventually, they said, “yes, the graveyard was on their property, but they had no plans to disturb the site.” They didn’t know who was buried there. Were there convicts there? They didn’t have a staff historian. So most of the questions we wanted answers to, they could not respond to, at least immediately.

The details do exist. They continued to say in that statement that they would be pleased to meet with members of the community and they would be willing to consider a memorial plaque if members in the community wanted that. So I think there is a door open there, and that’s something we haven’t seen before.

We spoke with Ellen Spencer, who is the president of Pratt City, and she very much would like to sit down and talk to them. She did say that she would hope for something more than a plaque. The fact that both sides want to sit down … are willing to sit down and talk about this may mean that there’s going to be real acknowledgment of the history that so far has been largely ignored or even misrepresented.

Reveal airs Sundays at 3 p.m. on WBHM. You can learn more about Alabama’s convict leasing system in our podcast Deliberate Indifference.