This story is part of a monthly series called Outdoor Connections, which features stories that explore the biodiversity of Alabama and how we depend on it.

Travel to northeast Alabama in the summertime to witness a natural phenomenon.

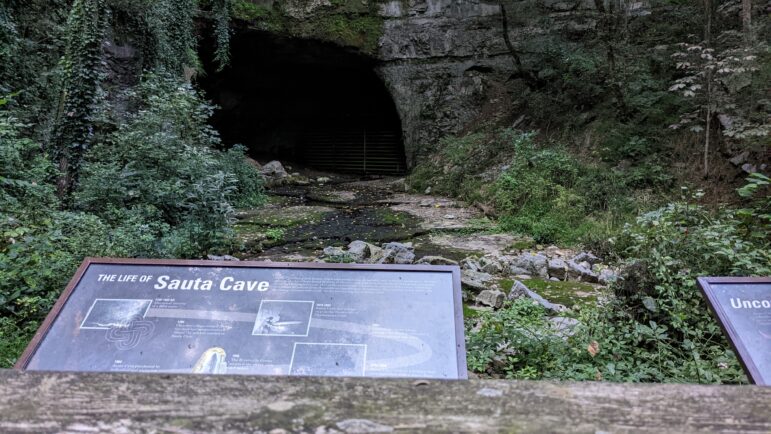

At the entrance to Sauta Cave, just off Highway 72 in Scottsboro, anywhere from 200,000 to 500,000 gray bats emerge to feast on insects.

It’s thought to be the largest emergence of bats east of the Mississippi River, a spectacle that draws curious onlookers from across Alabama.

“I love to do anything that has to do with the outdoors, and weird Alabama stuff that you can’t find anywhere else,” said Valerie Hollingsworth of Trussville.

In early September, Hollingsworth and her family joined a handful of people at the viewing platform directly in front of Sauta Cave.

“You can hear the tree frogs and the sun is going down. You can feel the air as soon as you get close to the cave. It’s about 20 degrees cooler,” Hollingsworth said.

Her 10-year old daughter noted a slight whiff of bat poop in the air, but it didn’t deter the group’s excitement as they awaited the show.

Soon after sunset, they looked up to the sky as bats began filtering out of the cave’s gated entrance.

The animals formed circles in the air, feasting on mosquitoes and moths.

“It’s really a natural phenomenon that’s worth seeing at least once,” said wildlife biologist Nick Sharp. “They’ll travel as much as 30 miles in a night hunting insects, and they may or may not come back to Sauta cave that night.”

Alabama is home to more than 6,000 caves, which lure bats with consistently cool temperatures and access to tasty insects.

Sauta Cave is particularly popular, with its large opening and location adjacent to the Tennessee River. It draws hundreds of thousands of bats, who spend their summers roosting inside, clinging to the walls and ceiling.

As cooler temperatures arrive, the flying mammals migrate to a nearby cave, Fern Cave, where they spend the fall and winter months hibernating with even more bats.

Sharp, who leads the Bat Monitoring and Conservation project with the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, calls Alabama the “heart of gray bat territory.”

“We have the largest gray bat summer cave on the planet. That’s Sauta Cave. And we have the largest gray bat hibernaculum on the planet. That’s Fern Cave,” Sharp said.

Gray bats may appear plentiful on a summer’s night in Scottsboro, but the animals haven’t always thrived.

Partly because their cavernous homes are also popular among humans.

“Native Americans used caves way back in time for habitation sites, for ceremonial sites, for resource extraction sites,” said Jan Simek, an archeologist who’s studied caves across the Southeast.

Simek said Sauta was originally part of a Cherokee town called Sauti, which was established in the late 1700s.

There’s evidence that the Cherokee leader Sequoyah often visited the town, raising the question of whether there might be writings of the Cherokee syllabary inside Sauta Cave.

“These caves were places where traditionalist Cherokees could record and emphasize aspects of their culture that they believed in. Sauta may well contain similar sorts of things,” Simek said.

In the early 1800s, the Cherokees rented the cave to European Americans, who used it for a mining operation. They extracted potassium nitrate from bat poop, which they used to make gunpowder.

The activity continued for decades after Native Americans were forced off the land.

In the early 1900s, Sauta cave was used as a nightclub, with a dance area established near the cave’s entrance to take advantage of the cool air. Years later, a developer planned to convert the cave into a tourist attraction.

“It’s probably the most documented site in Jackson County historically,” said David Bradford, Scottsboro resident and member of the Jackson County Historical Association.

Decades ago, Bradford and his wife explored Sauta Cave, crawling on their bellies through tight passageways to take pictures and discover formations.

The couple saw how centuries of human activity took a toll on the gray bat population.

“Apparently the bats made it through everything,” Bradford said. “They were decimated when we saw them, literally decimated. But they’ve recovered.”

Gray bats were listed as a federally endangered species in 1973. A few years later, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service purchased Sauta Cave and turned it into a national refuge.

Today, people are not allowed inside the cave, but they can watch the bats emerge from a distance.

The best time to see the spectacle is midsummer soon after sunset.

Do you have an idea worth featuring as part of our Outdoor Connections series? Email maryscott@wbhm.org.