Lisa McNair’s name was tied to Birmingham’s history from the moment she was born.

“I was born almost exactly a year after [Denise] was killed, and so I was kind of a miracle baby,” she said.

McNair’s sister, 11-year-old Carol “Denise” McNair, was the youngest of four girls killed in the racist bombing of Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church on Sept. 15, 1963. The attack was by members of the Klu Klux Klan. It marked a seminal moment in the civil rights movement.

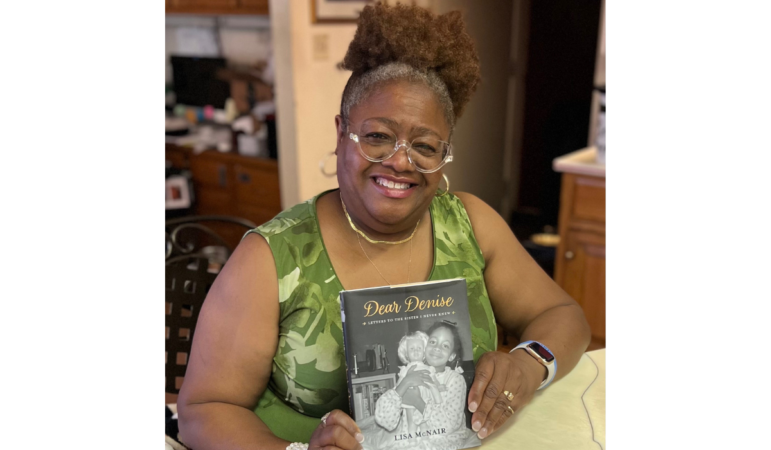

Lisa McNair grew up in the first generation of African Americans after legal segregation and recounts that experience in her memoir Dear Denise: Letters To The Sister I Never Knew, which is out Tuesday — the same week as the 59th anniversary of the church bombing.

Her recollection of what happened to the girls was sometimes challenging because of what she described as a culture of silence within the African American community.

“I think it was kind of a protective thing not to talk about it because if you had to think and talk about it all the time, you’d just be so frustrated and devastated all the time with the lack of respect you got as a human being on this earth,” she said.

McNair wrote that she was a teenager before she found out who the other families were that lost children in the bombing. She said the sentiment among her church culture was to turn it over to God and pray for vindication.

You’re ‘a white girl’

After her sister was killed, McNair’s parents, Maxine McNair and former Alabama Rep. Chris McNair, decided to send her to a mostly-white school, Advent Episcopal School.

“My whole thought process was ‘they’ve gone crazy. This tragedy has caused them to lose their minds … they are trying to kill me,” she laughed.

Eventually, her time at Advent became a memory she cherished. She said instead of racism she experienced encouragement and acceptance.

But as her perception of white people changed, so did her perception of Black people. McNair didn’t have a lot of Black friends except for a few kids in her neighborhood and some family.

She wrote in her book:

“Going to school with upper and middle-class white and Black kids gave me the sense that everything for Black people was a-okay. When I saw Black folks on TV complain about racism and how they were mistreated, I found it annoying … What I didn’t understand was that my thinking echoed that of the people with whom I spent most of my time, the folks at school — white people.”

McNair said she had to “try hard” to fit in with the Black kids and would oftentimes find herself reading an encyclopedia or playing with her dogs instead. Being called “a white girl” was the kicker.

“It hurt because it meant first, at some level, I wasn’t being authentic to my Blackness, or I wasn’t acting Black enough,” she said. “But then also knowing that my sister died for the cause, how dare I not be Black enough and she died for it? But none of that was true. I wasn’t trying to not be Black enough.”

As she got older, McNair said she not only didn’t fit in with the Black kids her age but she also started to feel a separation from her white friends. This created a sense of loneliness and eventually led to suicidal thoughts.

“I felt like I didn’t want to be here anymore. I’m tired. But how do I do that and take another child out of my mama and daddy’s life?” she said.

Relying on her faith

McNair said her Christian faith is what helped her get through the loneliness and suicidal thoughts, mourning a sister she never knew and, eventually, the death of her parents.

Her relationship with Jesus Christ is a focal point throughout her book. McNair grew up splitting time between two churches. Her mom attended 16th Street Baptist Church. Her dad attended a Lutheran church. As an adult, she joined Sardis Baptist Church and enjoyed its thriving singles ministry. But in the early-2000s, after much prayer, McNair became a member of Dawson Family of Faith, a mostly-white Baptist church in Homewood.

“It’s only a God thing because that makes no sense,” she laughed.

McNair wrote in her book that she expected to experience some racism when she joined that church. She says that has happened to a degree but it wasn’t “overt.” For the most part, McNair said she’s received only love from people at Dawson. But it’s her faith that has helped her respond to racism.

“The core thing I find from Christ is that he teaches love and how much he loves us – each one of us. No matter what the worst thing we’ve done or said. He loves us,” McNair said.

Justice rolls down

Eventually, three people were found guilty of the bombing: Robert E. Chambliss, Bobby Frank Cherry, and Thomas E. Blanton, Jr. A fourth suspect, Herman Frank Cash, died in 1994 before being charged.

But it took almost 15 years after the bombing before the first suspect was convicted.

In her book, McNair revealed that Chambliss wrote a letter to her parents asking them for help to get him out of prison. She also shared a story of becoming friends with Tracy, a woman whose father was a person of interest in the case but was never charged.

McNair also explored her experiences of falling in love, her “daddy’s dilemma” after he was convicted of bribery and conspiracy charges in the Jefferson County sewer scandal, and tackling tough questions like when she asked her mom whether she was supposed to hate white people for what they did to Denise.

“She immediately said no, that we are not supposed to hate white people. We’re supposed to love everyone like Christ loves us,” McNair said. “If she had said I have to hate all white people, then that would mean I have to hate all my friends in class, had to hate all my teachers and as a child, I didn’t know how I was going to only love Black people and hate white people. It just didn’t work. It was going to be way more work than my little mind could grasp. Her answer to love everybody was simple.”