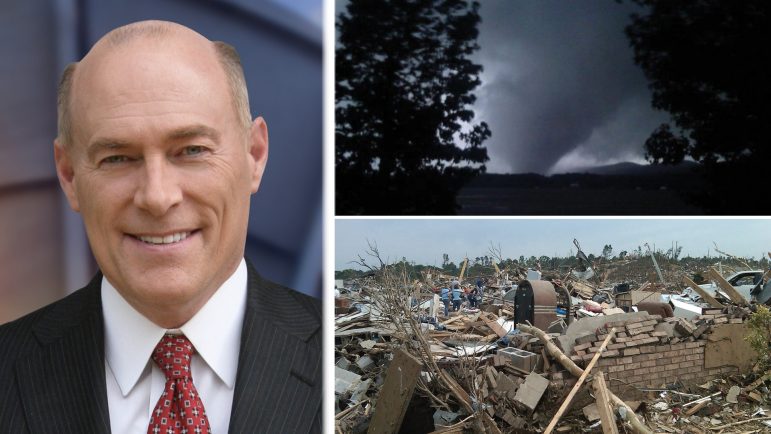

Tuesday marks the 10th anniversary of a once-in-a-generation tornado outbreak that ripped across Alabama. The storms killed 252 people. On April 27, 2011, James Spann, the chief meteorologist at Birmingham TV station ABC 33/40, spent hours live on the air as 62 tornadoes hit the state. Spann is an icon in Birmingham, a familiar face people turn to during severe weather. But for Spann, a calm and consistent presence on the screen, that day still leaves him unsettled.

“I’ve really not processed everything that happened that day 10 years later. I don’t think I ever will,” Spann said. “That day will certainly be part of my soul for a long time.”

Spann knew almost a week earlier that models were pointing to dangerous weather. A few days before, it became clear violent, long-track tornadoes were likely. But he admitted he did not expect the initial round of storms to be as powerful as they turned out to be. He planned to work from home before going to the station later in the morning. Instead, the first tornado warning came down about 4 a.m.

“That was probably the quickest shower I’ve taken in a long time,” Spann said.

He sped to the station and joined colleagues for live coverage for the morning round of storms that lasted until about 9 a.m. Those tornadoes damaged equipment and internet service which sent engineers scrambling ahead of the worst weather expected later in the day. The afternoon round started with an EF-4 tornado with peak winds of 175 mph that rolled over Cullman. No one died.

“I’m thinking, ‘ok, maybe we’ll just get through this,’” Spann said. “But as the day went on it was just like bullets from hell. It was horrific.”

The tornadoes kept coming. Sometimes multiple deadly tornadoes were on the ground at the same time. Late afternoon and into the early evening a tornado tore through Tuscaloosa very close the University of Alabama. It traveled on to hit the western suburbs of Birmingham, the city’s Pratt City community, before lifting near Tarrant. That tornado alone caused 65 deaths and 1,500 injuries.

The day kind of passed him by, Spann said. Because he was so busy, he couldn’t be caught up in emotion or note its significance in the moment. That focus was a good thing for Spann, who said his job is to be coherent and tell people what to do without being hysterical. Nevertheless, the task was immense.

“There’s no manual on how to handle that on live television. You just do the best you can,” Spann said.

Recovering Emotionally and Professionally

Earlier in his career, Spann said, he could have found some separation from a tornado outbreak. He could have paused, taken a walk and reflected. That became harder with social media and its onslaught of pictures and video. There was also a journalistic responsibility to cover the tornadoes.

“Maybe about a week later I was sitting at the breakfast table with my wife with just a few minutes and I just kind of broke down and had a good cry,” he said. “Sometimes a good cry is good for your mental health.”

But the storms laid Spann low professionally. With more than three decades of experience at that point, he thought “I’ve got this figured out.” Instead, he said, the tornadoes showed his shortcomings.

“Two hundred fifty-two people died on my watch and that’s absolutely inexcusable for anyone in the weather enterprise,” Spann said.

He didn’t talk about the tornadoes for six months, going through what he described as a grieving process. After that, the outbreak became motivation to become better at his job. He began discussions with social scientists to figure out new strategies to prevent deaths during severe weather.

The biggest contributor to the death toll, according to Spann, was the “siren mentality.” That refers to people expecting to hear outdoor sirens for weather warnings. Such sirens are only intended to reach people outside, meaning many people in buildings never knew the tornadoes were bearing down on them.

“I want to take them down and burn them,” Spann said.

Another factor, which Spann blames himself for, is the lack of helmet use. A common cause of death from tornadoes is blunt force trauma to the head. Even a bicycle helmet can provide protection.

“For so many people that died April 27, if they would have had a helmet on, they’d be alive today. I didn’t promote that. I didn’t push that,” Spann said.

A third factor is a high false alarm rate. According to Spann, the vast majority of tornado warnings issued by the National Weather Service were false alarms in 2011. That meant some people would ignore them. Meteorologist have since worked to reduce that number and Spann says the false alarm rate is now around a third.

The public has learned better practices and forecasters have improved, Spann said. He pointed to two outbreaks in March in which only five people were killed.

“We’re making great progress and a lot of the progress is because of the lessons learned April 27, 2011,” he said.

Marking 10 Years

Spann had no plans to mark the anniversary. He has been writing a book about that day and said he’d be “haunted” if he didn’t. He also has a goal to memorize the names of all 251 victims. (Another victim was an unnamed baby born pre-maturely.)

“I will be pondering that day, on some of the people and the stories, think about their families and pray for them,” Spann said. “Because they hurt just as bad today as they did 10 years ago.”

You can hear more about how the tornadoes affected Spann from NPR’s Invisibilia.

Photo by Wjalex4