Twenty-two candidates are on the ballot in Tuesday’s election for nine seats on the Birmingham Board of Education. Whoever is elected to oversee the education of 22,000 students will face challenges related to COVID-19 and its effects on students, teachers and staff.

For parents, educators and community organizations, student success is a big concern which is why they are invested in this year’s school board election.

“Education is the fuel that drives economies,” said former Alabama House of Representatives member Ronald Jackson, who now leads the group Citizens for Better Schools and Sustainable Communities.

The public policy organization advocates for education and community development in Birmingham. Jackson said the school district has some work to do and it is time for the public to hold the school board accountable.

“The U.S. Department of Education does, and they expect local school boards to measure up to it, and when you don’t, the public must rise up and say ‘failure after failure is not acceptable,’” Jackson said. “How long is it going to take for this city to close the academic gap in Birmingham, Alabama schools?”

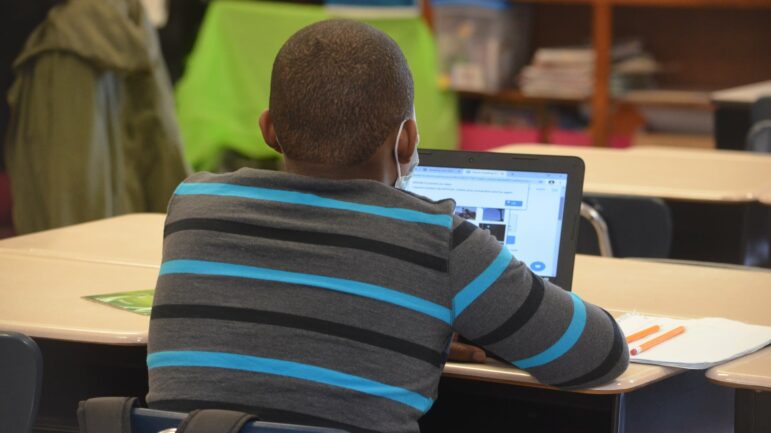

After a year of virtual learning, students and teachers are having to play catch-up more than usual for academics.

“Children are behind. They’re not where they typically would be at that time of the school year,” said Jennifer Summerlin, an assistant professor at the UAB School of Education who looks at K-12 learning trends.

In a normal year, students usually lose about 20% of what they learned the year before. But with COVID disrupting class, that loss is much greater. In Birmingham, learning loss also increases when families lack internet access or other opportunities and resources.

“For school board members and for families, we have to remember that we all have to work together to overcome this,” Summerlin said. “But we also need to be mindful that people have been through a lot and they’re not necessarily going to walk back in and just hit the ground running to where we left off.”

Another complex issue the newly elected school board will have to tackle is funding. Birmingham City Schools received $119 million in federal relief funding. A quarter of that American Rescue Plan money is supposed to address learning loss. That means $29.5 million will go toward student enrichment programs and other initiatives.

Carol Gundlach, policy analyst at Alabama Arise, a statewide non-profit that advocates for low-income families, said this federal relief money could be “revolutionary” for the district, but it does not solve systemic funding problems at the state level.

“The greater context is that Alabama has historically, all the way back certainly to 1901, restricted funding for our school systems,” Gundlach said. “And in such a way that it protects the interests of the wealthy over the needs of the children.”

In Alabama, school districts received funding based on property taxes. So districts with valuable property get more money and areas with less valuable property get less money. The state then equally divides funding based on the number of students in schools, but Gundlach said that doesn’t take into account disparities that already exist at the local level.

For example, Birmingham City Schools has had challenges in making sure families have access to technology, schools have experienced teachers, and other systemic barriers facing the district.

“So all of those things make it really difficult for school boards to do what they know they really need to do to adequately fund education because their hands are tied in their ability to raise the money that’s needed,” Gundlach said.

Gundlach said many underfunded schools must rely on local fundraising, a task the school board will have to address.

“I think this is really about democracy and about making sure that the people whose institutions these are have a voice and … how they’re run,” Gundlach said.

Many advocates say the school board needs to keep students at the center of all their decisions and to do that they need to listen to their parents.

At a recent Birmingham City Schools town hall, incumbent school board member Daagye Hendricks responded to concerns about making decisions for students.

“We are being as transparent as possible,” Hendricks said. “We do not want to make decisions for your children without your input.”

Rachel Harmon is the executive director for Birmingham Promise which addresses economic mobility for students. She said she thinks the school board could be doing more to engage parents.

“You’re not only solving for what happens inside a school building, you’re solving for constrained economic opportunities that parents experience and their communities experience,” Harmon said.

Nearly 70% of children in Birmingham City Schools come from lower socioeconomic homes. Harmon works closely with parents and she said they care about their children’s education, but they might not always have time to attend school board meetings, especially if they’re working.

“ [It] ultimately boils down to do parents feel that they are able to influence outcomes? And no matter what sort of adjustments that you make from a logistical standpoint, if parents don’t feel that their voice matters in a process, I don’t think it’s fair to expect them to participate in it,” Harmon said.

Kyra Miles is a Report for America Corps Member reporting on education for WBHM.