By Nick Patterson

You don’t have to get infected by the coronavirus to see it have a painful impact on your life, as many workers – or former workers – have discovered.

Christine Prichard, a freelance photographer based in Birmingham, has seen the impact of COVID-19 in a couple of ways. First, her teenage son is in the Dominican Republic and she’s eager to get him back home, even though that would mean two weeks of quarantine with him.

But like many others, Prichard is seeing her business affected by the pandemic, as well.

She frequently shoots photos of corporate events, and late last month, at an annual celebratory event for a trade group, she saw an early sign that the pandemic was going to have an economic downside for her work.

“It was their annual meeting to kind of celebrate their sales. And at that meeting every year they would announce where they would book their annual trip for the top sales people of this product. And there was a guy that had to announce that they were not going to book the trip, pending what’s going on with coronavirus,” she recalled. “He said, ‘It’s just too iffy. We don’t want to lose deposits. We’re being super-careful.’”

That, Prichard said, was “kind of the first little wind I got that, ‘Oh. This could really be an issue.’ Not only just for me, but just for the economy as a whole. But I knew, since a nice chunk of my business is covering events. I just knew it was going to affect it and it has … I haven’t done an event in a couple of weeks.”

So far, she’s had headshot portrait sessions for an insurance company canceled, and her bookings are down. “A lot of my bookings are kind of last minute, so usually one to two weeks out,” she said. “And it’s been crickets this week.” A brokerage she works for “canceled all their shoots,” for a two-week period. “I have some shoots booked the following week … but I’m pretty well expecting to get canceled.”

From gig workers, to teachers to even health care workers and others, many are finding that the pandemic has reached into their pockets.

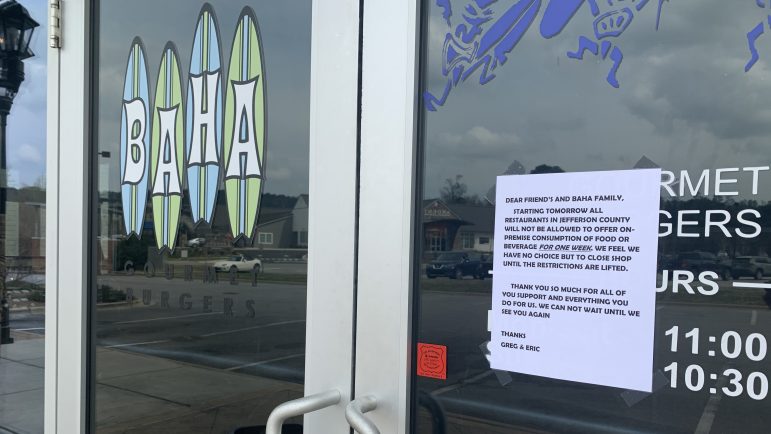

Jefferson County residents disrupted by the coronavirus pandemic took another hit in recent days, as more businesses were added to the list of those having to close by order of the county health department. Then Birmingham issued a shelter in place order.

The pandemic has economic forecasters talking about recession in the wake of massive jobs losses. The headlines are about plants closing, unemployment claims rising, the government working on details of stimulus relief to American workers – and failing to come to terms. An NPR/PBS Newshour/Marist poll said that by last Wednesday, “nearly 20% of U.S. households have experienced either a layoff or a reduction in work hours because of the coronavirus.”

Unemployment filings are rising significantly. Preliminary Alabama Department of Labor numbers show that more than 17,000 people filed for unemployment on Sunday and Monday, the Associated Press reported. In the week that ended March 20, 9,347 claims were filed in the state. And the week before that, 1,434 claims were filed.

Nationwide, the number of people filing for unemployment grew to 281,000 in the week ending March 14, which is an increase of more than 70,000 from a week earlier. The U.S. Department of Labor said on its website that the increase was “clearly attributable to impacts from the COVID-19 virus.”

“A number of states specifically cited COVID-19 related layoffs, while many states reported increased layoffs in service-related industries broadly and in the accommodation and food services industries specifically, as well as in the transportation and warehousing industry, whether COVID-19 was identified directly or not.”

The Common Dreams organization analyzed news reports to predict that 3 million or more people could have filed unemployment claims for the week ending March 21, which would be the highest number in American history.

Calls for Extending Unemployment

Alabama Democrats Sen. Doug Jones and Rep. Terri Sewell issued a statement urging Gov. Kay Ivey to extend unemployment benefits for Alabamians impacted by COVID-19.

Noting that Alabama recently decided to cut unemployment benefits from a maximum of 26 weeks to between 14 and 20 weeks, the lawmakers said the changed circumstances caused by the virus calls for a change in policy.

“As a result of the economic and public health crisis caused by the virus, many workers have had their hours cut or have lost their jobs entirely,” they said in a joint statement.

Writing to the governor, they said, “We urge you to work with the State Legislature to make available twenty-six weeks of unemployment benefits for all eligible individuals for the duration of this public health and economic crisis. This action would be an impactful step to maintaining economic stability during this challenging time. … We are facing unprecedented economic upheaval, and families will increasingly rely on these funds to afford basic necessities, including food, housing, and medication. One of our top priorities must be to support workers and families facing difficult financial circumstances due to the pandemic.”

Unanticipated Repercussions

The economic toll is touching people in surprising lines of work. Some nurses at Grandview Medical Center, for instance, say that the pandemic is costing them.

Two nurses who outlined their situation asked not to be named in this article.

“None of us can afford to get fired, right now,” one of them said.

The other nurse said the reason the pandemic is costing them is that the risk of infection has caused surgeries to be canceled.

“The problem is we cannot do elective cases and surgery, which makes sense. You don’t want to bring healthy people into an environment where there are sick people because of the virus. So our caseload has dropped,” she said, adding that, instead of the 36 hours a week she normally works, she expects to work this week only 16 hours. The time off will only be paid leave if she’s accumulated enough paid time off. Grandview will not allow her to take sick time she’s accrued unless she is actually sick, she said.

“There are hospitals who are actually paying their employees because they can’t come to work, because they don’t need them here – the VA, Children’s, St. Vincent’s. And basically here, if you don’t have what they call paid time, then you don’t get paid. … All the other hospitals in the city are taking care of their employees.”

The nurse said that, while she makes more than many employees at Grandview, “My home is budgeted on the amount of money I make … There are people here who have no paid time off – single parents who are already working two jobs to make ends meet.”

The other nurse said the economic impact caught her by surprise at the same time as her husband, a small business owner, was likewise impacted. “So for us, we’re getting hit twice,” she said. “When this was all coming about, it never even occurred to me – never even crossed my mind that I would be at risk of not getting a paycheck. I mean, I work at a hospital.”

Grandview responded in a statement provided by marketing director Leisha Harris: “The COVID-19 outbreak has had a major impact on the healthcare industry in a very short period of time. Hospitals and medical offices across the country are experiencing changes in their day-to-day operations, patient volumes, scheduling, screening of patients, procurement of supplies and staffing practices.

“We have the utmost respect and gratitude for our Grandview health care teams’ contributions to our community need day-in and day-out. These are challenging times, and we are all learning to be flexible and to use all our resources wisely. When it comes to our personnel our goal is to ensure their safety and availability for what could be a prolonged period of disruption. We continue to work to develop creative ways to utilize our staff in areas of greatest need and to provide access to their benefits to assist them with the financial impact of this crisis.”

Sudden Crash

The shape of this particular pandemic-fueled economic disturbance is similar to the 2008 recession, but it also is different in important ways, said Peter Jones, assistant professor in UAB’s Department of Political Science and Public Administration.

“We clearly saw something similar in terms of the stock market and unemployment and things like that in 2008. So, in terms of where this may go, we’re not in historic terms just yet,” he said. “I think the main difference is just the speed by which this thing has kind of taken off … In 2008 it did take us by surprise, but the steps were longer term. Yes, businesses started shutting down but it wasn’t all at once. And the reverberations of that stock market crash really didn’t hit like it has now.”

Renerpho – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

The Dow has crashed since the novel coronavirus first began spreading.

Jones predicted that, “Long term, we’re clearly going to see unemployment rise,” but said that how much will depend on what the federal government does about it. He said that a “strong stimulus response,” with the government offering income assistance, freezing evictions and foreclosures and taking similar measures could prevent the economy from continuing to worsen, and “give people a life raft now so that they can kind of prepare and mitigate any disasters long term.”

It will be important for any government stimulus package to be big enough to really make an impact, Jones said, noting that the Obama administration’s stimulus efforts may have been too small in retrospect.

“It was clearly a huge stimulus package at the time,” Jones said. “But one of the critiques has been that it probably should have been larger — not because short term … people clearly lost their jobs but long term, just localities and states, it really took a long time for those places to get back.

“Just one example: Alabama. It took Alabama 10 years to get back to pre-recession education spending and so a large stimulus package now may clearly help in the short term, but it might help states and localities and individuals recuperate and return much more quickly.”

Another result of any coronavirus hit on the economy is likely to be political, Jones said.

“This thing will be probably the biggest issue for the 2020 presidential campaign and down-ballot, too,” he said, adding that lawmakers should expect that “your political life is on the line in what you do here … We’re collectively paying attention to this like few events ever and so politicians are on the hot seat as they’ve really never been before.”

That actually works in favor of a substantial stimulus response, he said. “As this thing changes daily, anything is on the table and I think the political will for it is increasing.”

Andrew Butters, assistant professor of business economics and public policy at the Indiana University Kelley School of Business, said that some aspects of the downturn are hard to predict and not likely to show up right away.

“I certainly suspect that the timing of this is going to be such that it might even imagine that while the Q1 number comes in maybe lower than initial forecasts it’s still commensurate with expansion of economic activity, and that where some of the real significant downside risks are I think would be showing up in Quarter 2,” Butters said.

“Now, of course, part of an unfortunate situation when it comes to broad measures of economic activity is that we’re not going to really have the final, final tally on that in terms of relationship to Q2 for still several, several months’ time.”

Butters said that the pandemic-driven economic decline, which he fully expects, still has too much unpredictability attached.

“We can see all these shut downs, we see plants temporarily halting, we see schools closing, we see businesses shuttering their doors, but there’s still a very large amount of uncertainty regarding just how long those responses and those actions are going to have to take,” he said.

Still, he said, with an economy that was on an upswing before COVID-19, there is hope for a strong rebound if politicians and health care professionals can formulate a plan that shortens the depth and duration of the economic contraction.

“As quickly as we can remove the vast amount of uncertainty that there is out there, is the way we both rebound quicker and in some respects maybe rebound stronger,” he said.

Such measures include “making sure that we’re doing everything we can for the health care industry and health care workers and keeping them safe,” he said.

Adjustments Required

Meanwhile, though, workers are finding that they have to make sometimes significant adjustments to ride out the economic storm.

Photographer Christine Prichard is more used to ups and downs in her economy than some, because she’s been freelancing for years. “I don’t really have a plan. I can kind of ride things out for a little while,” she said, noting that she has taken a short-term job as a census taker and that she has income from a rental house and some stocks.

Still, where she had been having a good year in 2020 – double or even triple her income in January and February over the same period last year – now she predicts her income will be down from that by 75% or more over the next month.

Even for someone with her experience, Prichard expects to feel the impact of coronavirus on the economy. Despite that, she sounded a hopeful note about a public, private, civic partnership in Birmingham dedicated to helping people dealing with various problems caused by the pandemic, including financial problems. She said that the program, Bham Strong, makes her proud of how some local leaders are grappling with the issues caused by COVID-19.

The organization is working to help struggling businesses get loans, to determine the needs of business owners and to help hard-hit employees find work. According to Prichard, it’s that kind of support that will be needed to help the economy recover from the ground up. “It is so refreshing,” she said, “to hear people who are on the ball, have a plan, and are logical.”

Policy makers should help consumers realize a return to the mindset they had a short time ago, when they were not so worried about healthcare concerns, Butters suggested.

“If we keep our eye on the prize and make sure that those same consumers (know) we’re doing everything we can to keep them healthy and allow them to, as quickly as possible, feel that their own health is not in jeopardy … participate and engage again in terms of the broader economy, that, at least in my view, is going to be the best way for us to find our way out of this,” he said.