From Florida to Texas, oyster populations in the Gulf of Mexico are dropping, and in some places, they are at historic lows. In Alabama, the problem is so bad that officials canceled this year’s public oyster season. Scientists involved in restoration efforts are now finding that what worked before is no longer working, so biologists are trying something new.

Empty Reefs

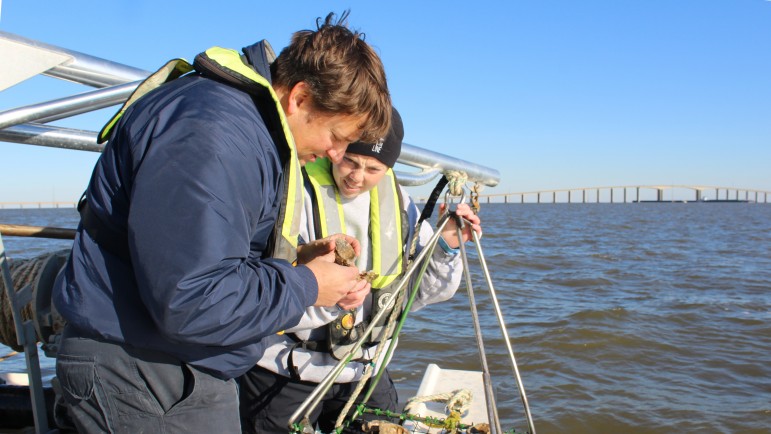

Off the coast of Dauphin Island, a team from the Alabama Marine Resources Division is in a small boat headed to a nearby oyster reef. Winter is the ideal time to harvest oysters, and normally the bay would be crowded with fishermen. But today, this is the only boat in sight.

Biologist Jason Herrmann is leading the team. They are on the water to perform a spot survey, checking for live oysters on the reef. Herrmann does not like what they find.

“Twenty-two half shells. Nothing,” he says.

That is, 22 empty shells, no live oysters. It is not a surprise. Alabama used to produce more than a million pounds of wild oysters in a year. Right now, the state’s public reefs are closed and have been for months. Last fall, biologists could only find five legal-sized animals during the pre-season survey. Oysterman Phelan Ray Foster says he has never seen it so bad.

“I can remember when I was, say 20 years old,” Foster says. “I seen more oysters come off that reef in one day than what’s come off that reef in the last eight, nine years.”

What’s Worked Before

The decline is happening throughout the Gulf of Mexico. It is particularly bad in Alabama. That is despite the fact that the state has invested millions of dollars in recent restoration projects, mostly with funding from the 2010 BP oil spill settlement. One of the most common techniques is to submerge old oyster shells and rocks to give baby oysters something to attach to, allowing reefs to replenish themselves. But biologist Jason Herrmann says this is not working like it used to.

“The material that we put down is doing what it was supposed to do,” Herrmann says. “The problem is there’s just such high mortality. The survival is just not happening.”

The reasons oysters are dying, Herrmann says, is complicated. There have been hurricanes and drought. There is pressure from development and overharvesting, and potential long-term impacts from the BP spill. Whatever the reason, reefs are not rebounding, so state biologists are trying something new.

A Restoration Hatchery

Max Westendorf works at the Claude Peteet Mariculture Center in Gulf Shores. This space will soon be home to a new oyster hatchery, recently funded with $3 million in settlement money. The facility will grow baby oysters to be planted on wild reefs. Westendorf says it is a step up from planting empty shells.

“Everything’s reaching a big scale right now,” he says. “You know, we’re looking at setting millions and millions of oysters, if not billions.”

Similar efforts are happening in Washington state and the Chesapeake Bay. But restoration-based hatcheries are fairly new to the Gulf Coast. It is not a fix-all. The idea is to give reefs a boost to survive environmental conditions. Biologist Jason Herrmann is hopeful.

“Everybody wants the, ‘Hey, what do you consider a successful restoration?’ or something like that,” Herrmann says. “And the best answer that I can give is, ‘Well instead of five boats out here, I’ve got a hundred boats out here, fishing for oysters.’”

If all goes well, biologists will plant the first oysters from the hatchery in summer of 2020.