Birmingham has a workforce problem. A recent report by Burning Glass Technologies projected thousands of future jobs, especially in information technology, but many potential candidates don’t have the skills to do to the work.

City and business leaders say Birmingham’s economic future is at stake. They hope programs like Innovate Birmingham, along with a multi-year partnership with the Brookings Institution and other initiatives will help grow the city’s workforce.

Blake McCracken, a 25-year-old Vestavia Hills High School graduate, is looking for more opportunity in Birmingham. He’s learning to code through a course at Innovate Birmingham.

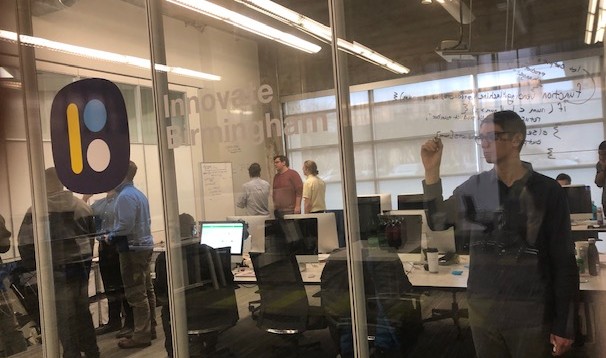

On a recent morning, he worked with a team of people in a glass-enclosed classroom at Innovation Depot in downtown Birmingham. They hovered around computers and scribbled on boards working together to solve problems.

McCracken says he has one goal when he completes the program this spring.

“I just want to get to a job,” he says. “ I’ve been valet parking cars for about six years off and on and I’m really ready for something that’s more fulfilling, something that pays better.”

Building up the area work force can help improve the quality of life in the region, leaders say. Almost a third of Birmingham residents live in poverty and thousands either work low-wage jobs or are unemployed. Studies show many of the unemployed or underemployed are young adults.

Innovate Birmingham programs serve people ages 17 to 29.

“We’re trying to figure out the right chicken or egg problem of training the talent or having the jobs, and which comes first and how do we do those at the same time to grow the entire economy,” program director Haley Kendrick says.

People who complete the training programs can land entry-level jobs that pay from 12 to 25 dollars an hour, Kendrick says.

A lot of the students have grown up using technology, so it’s a good fit, she says.

“They are very comfortable with iphones and tablets and computers. But learning the background of how it works is something that is new but tends to be exciting,” Kendrick says.

Once participants learn entry-level tech skills, they can work toward mid-level jobs where there is also an increased demand for employees, Kendrick says.

But building up Birmingham’s talent pool is only part of the challenge. Jonathan Nugent with the Birmingham Business Alliance says the city needs to attract more people from out of state — and get them to stay. That includes students who often leave once they’ve obtained their degrees. And, Nugent says, the city needs to land more startups.

He says there’s been some progress.

“The flow of startups means it becomes more of a vital city, more vibrant,” he says. “Young people are coming here and moving here and liking it here.”

But recent studies show another gap in workforce development. Area colleges and universities don’t produce enough graduates to fill projected jobs. The biggest demand is expected in information technology, bio sciences and advanced manufacturing.

Josh Carpenter, head of economic development for Birmingham, says he’s optimistic. But he acknowledges things like poverty and access to education are challenges. Carpenter spoke at the event kicking off the partnership with the Brookings Institution and said Birmingham is at a critical moment.

“We’re at an inflection point as a community,” Carpenter said. “Either we change, and join the cities that are on the vanguard of think through what’s next, or we go the way of the dinosaur.”

Mayor Randall Woodfin also spoke at that event at Sloss Furnace. He talked about the glory days of Industrial Birmingham and its transition to a center for health care.

Woodfin says Birmingham residents still possesses the energy that made the region an industrial leader. It’s that energy that will fuel the next transition, he says.