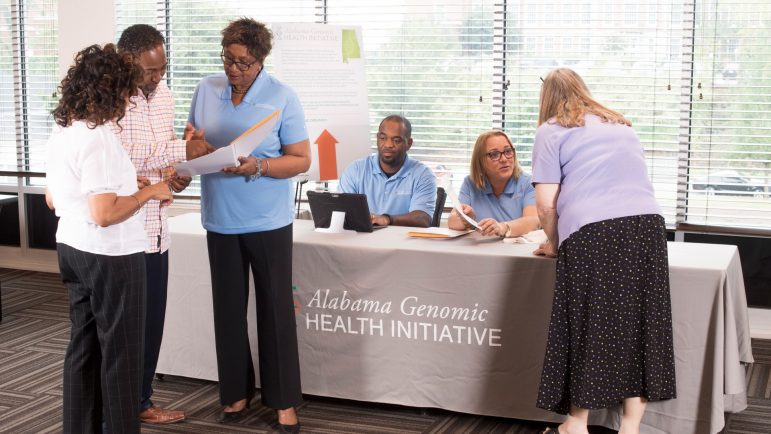

Twenty-four-year-old Erika Garrett is not afraid of needles. She didn’t flinch while giving blood recently at a pop-up clinic in Hale County, about 45 minutes from Tuscaloosa. Garrett is participating in the Alabama Genomic Health Initiative, a state-funded project that offers free genetic testing to residents. The pop-up clinic is an effort to reach people in rural parts of the state. Garrett is from the area and says she has been waiting a while for this opportunity.

“I’m here to get my genetic testing done because my mother has had breast cancer twice and she has, luckily, she has survived both times,” Garrett says.

Garrett wants to know if she is also likely to get breast cancer. The test will look for 59 genetic mutations tied to a higher risk for certain conditions, like cancer or heart problems. Geneticists and clinicians from UAB and the HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology are leading the initiative. Director Renie Moss says one to three percent of people will test positive for a mutation. These participants will receive advice from a genetic counselor about how to prevent and detect the condition.

“If you knew you had these markers, if you knew this ahead of time,” Moss says, “then all of these things are potentially actionable. And that’s really the goal is to give you more control of your health.”

And there is another goal. All participants have the option to add their blood samples to a biobank for future research. The Alabama Genomic Health Initiative plans to recruit 10,000 people who reflect the diversity of the state. Moss says that is especially important. A recent study shows that across the board, genomics research does not accurately represent all populations.

“Historically, those biorepositories and the data have been very Indo-European, very white,” Moss says. “That’s not Alabama.”

A broader understanding of genetics will be even more useful in the future, according to Dr. Bruce Korf, the chief genomics officer at UAB and a leader on the state project. Korf says right now, people may only associate genetics with diagnosing rare diseases or personalizing cancer therapy, but he expects that to change.

“You know we’re just beginning to see a real return of value from genomic medicine,” Korf says. “Go to sleep for a few years and wake-up and you’ll see a completely different picture.”

Korf says as we learn more about genetics, it will likely become a more routine part of medical care. The statewide initiative is a way to prepare both residents and health care providers for that future, through education and exposure.

“The goals here in part are to sort of test our ability to deploy genomic testing on a really wide scale to diverse populations in the state,” Korf says.

The Alabama Genomic Health Initiative began in 2017 and is expected to wrap up in 2022. The state is spending $2 million a year on the project. Korf says Alabama is one of the only states in the country to fund a study like this. He says it is even inspiring some plans for the national initiative All of Us.

Still, not everyone wants to participate. Some people are concerned about privacy, though study leaders assure data is secure and protected by an NIH Certificate of Confidentiality. Others might not want to know this kind of information. A genetic risk is not a diagnosis and does not guarantee one. But even so, knowing you are at risk for a disease can still cause anxiety.

Back in Hale County, Erika Garrett feels a little nervous. With her mother’s history in mind, she is thinking about what she will do if she tests positive for a higher risk for breast cancer.

“Well I’d probably cry first,” Garrett says, “and then I’ll probably see what is, what would be my best outcome would probably be UAB, go to UAB, where she has been twice.”

Going to UAB would mean driving over an hour and a half away for medical care. For now, Garrett will wait and see. She should receive her results in about two to four months.