If you can grow cancer outside the body, it’s easier to figure out how to kill it. With an eye toward faster drug development and more effective treatments, a UAB biomedical engineer has come up with a new way to sustain cancer cells. It’s a technical challenge, but Joel Berry knows how to explain his system in a digestible way:

“Think of it like making Jello at home.”

But instead of powder and water in a Jello mold for hungry people, it’s collagen in a silicone housing for hungry cancer cells.

“We put it all into a mold, and then we allow that collagen gel to actually form a solid,” says Berry. “And we keep everything profused with a nutrient fluid, and we keep it warm in an incubator, and it’s off to the races.”

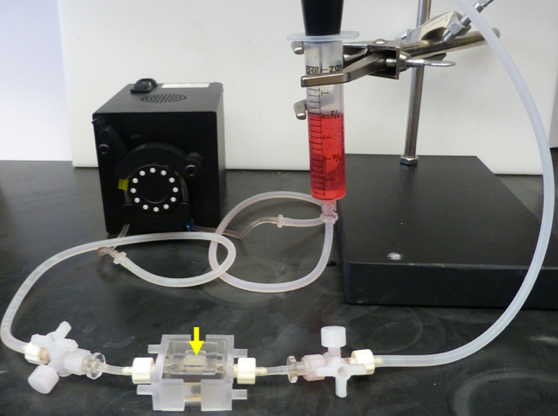

Berry calls it a “bioreactor.” The collagen framework inside the housing is intricate, but the whole thing measures only about a cubic centimeter. “Cubic” is key: it’s three-dimensional, unlike, say, a single layer of cells in a petri dish. So the tumors can have volume, as they would in a person.

“We’re going for realism in that we’re creating a three-dimensional tumor, and we’re introducing a flow which is meant to mimic blood flow,” Berry says. “It’s allowed us to do a lot of different things with tumors on the bench-top.”

The engineering feat here is making tiny structures that can withstand fluid being pumped through them and sustain different kinds of cancer cells. Berry calls himself a “plumber,” but he’s a plumber who hopes to play a role in finding faster, cheaper ways to fight cancer.

Zev Gartner, a pharmaceutical chemist at the University of California, San Francisco, points out that “it can cost anywhere from several hundred million to several billion dollars to develop and get new drugs approved by the pharmaceutical industry.”

He says the high costs and long duration of the process stem partly from drugs that show early promise – say, in mice – but later fail in expensive human trials. Gartner, who’s not affiliated with Berry’s work, says Berry’s bioreactors could cut those costs:

“One fantastic way of doing that would be to reduce the number of drugs that actually go into clinical trials that are likely to fail. And the best way of doing that is to have better models for the interaction of these drugs with humans.”

Along those lines, Gartner sees potential personalized benefits too. Sometimes drugs work for one person but not for someone else with the same kind of cancer. But, “one dream might be to be able to take a biopsy of a tumor and place it in a device and then screen say, 10, 20, maybe even a hundred different combinations of approved drugs and look to see which one works best. We might be able to actually take some of the guesswork out of what drugs to use.”

Berry says his team has made more than a hundred bioreactors and that cancer specialists at UAB are starting to use them in their own labs. If the system continues to work and spread, researchers could theoretically develop better treatments faster, and for less money.