By Hank Black

The Oliver Robinson bribery trial, in which guilty verdicts were issued for officials of Drummond Coal Co. and its law firm, Balch & Bingham, revealed a gritty episode about avoiding environmental cleanup in North Birmingham. But there’s a bigger dirty picture.

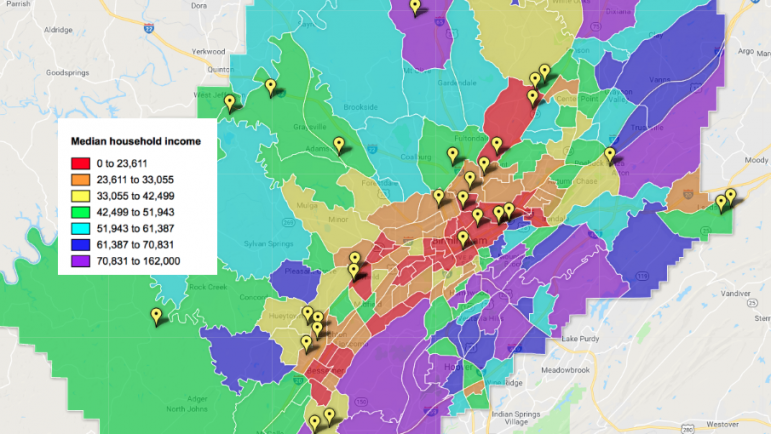

The vast majority of Jefferson County’s 31 major sources of pollution – those emitting enough pollution to require a permit under Title V of the Clean Air Act – are located in low-income areas, a BirminghamWatch analysis found.

The findings show 71 percent of the major pollution sources are in areas with incomes below the median income for the county.

Only one primary source of pollution is in a neighborhood with a median household income greater than 110 percent of the county median.

Residents of the same low-income areas also often are largely African American. Research has shown that economically depressed populations can be more heavily affected by the negative health effects of air pollution. Studies of the effects of pollution specifically on racial minorities have been mixed, with some investigations showing increased problems and others failing to show a correlation.

Poor air does not equally strike everyone in the Birmingham area, raising issues of environmental justice. Mayor Randall Woodfin’s transition committee on environmental justice and sustainability recommended working with the health department to develop a comprehensive plan for dealing with emissions.

“Some populations are more affected because of their distribution in the city and county industrial belt,” UAB lung researcher and physician Veena Antony said. People who live there are relatively poor and often African American. They historically worked in the mines, mills and factories and came to live near where they worked, she added.

Those residential areas also became legally defined, set aside in zoning laws a century ago that created redlined districts along racial lines, according to many accounts of Birmingham’s early history. The combination of industry and redlining helped create a kind of environmental injustice that was manifest in the Robinson corruption case. It highlighted how industries that poisoned air and soil of surrounding neighborhoods tried to avoid responsibility for that.

Pollution: Birmingham’s ‘Perfect Storm’

Industrial pollution is part of Birmingham’s heritage, born of the nexus of iron ore, coal and limestone that produced steel to undergird America’s economy. Cars and trucks are another part of the city’s history, reliance on which ballooned with the migration, mostly of white residents, from the city to its ever-expanding circles of suburbs. The interstate highway tentacles that crisscross the center of Birmingham encouraged the commuting.

Tie the dirty waste of industry to the emissions from motor vehicles. Layer this onto the natural topography of Jones Valley, where the county’s industry and employment are concentrated, and you can come up with what the Jefferson County Health Department calls “the perfect storm” to degrade the quality of the area’s air.

“The highest levels of pollutants are in Jones Valley – including north Birmingham, Wylam and Bessemer – where most industry and interstate traffic are located,” according to Matt Lacke, Jefferson County Health Department meteorologist. “Combine our topography and weather, and you have a perfect storm. If there’s an inversion, the pollution is trapped in the valley, since temperature decreases with height. If there’s no wind movement on hot, stagnant days, pollution collects near the ground and acts as a lid until conditions change.”

Historically, the air in the Birmingham metro area was among the dirtiest of any urban area, minimizing visibility, raining soot on clothes and rendering children, pregnant women, asthmatics and other vulnerable populations at risk of illness and early death. As late as 2011, Birmingham was ranked as the eighth most-polluted city in the nation by the American Lung Association, in terms of particle pollution.

The pollution began to lessen in the early 1970s with the birth of the Environmental Protection Agency and passage of the federal Clean Air Act, which regulates air emissions.

Earlier this year, the American Lung Association in its annual scorecard of air quality, ranked Birmingham 15th in the nation for most-polluted city for year-round particle pollution, based on 2016 figures. The two most widespread pollutants now are particulate matter (PM) and ozone, also called soot and smog, respectively.

Antony, the lung researcher and physician, acknowledged that air quality is greatly improved in the past 50 years but said it still is a major cause of morbidity and premature death.

“Industry is important to our community but can also contribute to pollution.” she said. “We still have times with a combination of excess heat, ozone, and particulate pollution that can be very detrimental to the health of our community, particularly for sensitive, vulnerable populations.”

In summer, when air quality is worse with ozone, she said, there is a predictable uptick of patients going to emergency rooms for acute asthma attacks, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and even heart disease with acute exacerbations of symptoms.

New Science, New Standards?

Reductions in ozone limits made under President Obama in 2015 are still in force. Contrary to a campaign promise made by President Trump, that’s not likely to be repealed or rolled-back. The Environmental Protection Agency, after studying that standard for a year, told a federal court on Aug. 1 that it will defend the 2015 rule against a lawsuit brought in part by former EPA chief Scott Pruitt while he was attorney general of Oklahoma.

The EPA’s standards for particulate matter in the air was set at 70 parts per billion in 2015. Although she calls that standard “very reasonable,” Antony is among those who would like to see that figure lowered in light of recent scientific study results.

People older than 65 “show even greater sensitivity to pollution than previously found as well as a linear increase in disease and presentations to emergency rooms even at air quality below the present acceptable standard,” she said.

A 2015 Harvard School of Public Health air pollution study looking at millions of deaths from heart disease, lung disorders and other causes in 75 American cities found that the effect of particles on mortality rates was about 75 percent higher in cities with a high proportion of sulfates from coal-burning power plants than in cities with little sulfate pollution. It was about 50 percent higher in cities with a higher proportion of particles from road dust.

Birmingham has both.

Why not stricter standards? Those are set by the EPA based on a review that includes independent advice from the federal Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee, according to Jonathan Stanton, director of environmental health services for the Jefferson County Health Department.

The Alabama Department of Environmental Management has authority over most air emissions monitoring in the state, but there are two exceptions: Jefferson County, represented by the Jefferson County Health Department, and the city of Huntsville’s Department of Natural Resources.

Jefferson County Health Department Role

Stanton said the federal advisory panel surveys research about air pollutants, their sources and strategies for attaining and maintaining air quality standards, then recommends the EPA either keep the same or lower levels for each pollutant.

The health department board cannot unilaterally, based on its own review of national scientific findings, change a federal standard, he said. The huge amount of data involved in a local pollution review makes doing that kind of health research “an impossibility,” he said.

However, Birmingham’s new government may have a role in tamping down air pollution. Mayor Woodfin’s transition committee on environmental justice and sustainability recommended working with the health department to develop a comprehensive plan for dealing with emissions but “focusing first on the reduction of criteria air pollutants.”

Gasp, a Birmingham air quality advocacy group, has urged the EPA and state and local agencies to more dramatically reduce air pollution and implement standards “more protective of human health,” according to staff attorney Haley Lewis.

When the 2008 ozone standard of 75 parts per billion was up for review by EPA, Gasp lobbied to drop the ozone concentration limit to 60 parts per billion. “That would be ideal,” Lewis said. “We thought 65 would be fine. But EPA went for 70.”

All of Jefferson County’s major polluting industries are now in compliance with standards for pollutants covered by EPA regulations. In fact, the entire state is in compliance, as announced in May by the director of the environmental management department.

With no change in the 70 ppb standard close at hand, “We absolutely must work through the health department and others to increase efforts to make an impact on communities that are more vulnerable simply because of where they are located,” Antony said.

“Government and health care institutions should increase efforts to educate at-risk populations to spend less time outdoors and limit activity during summer days of high heat and pollution,” she said.