By Sam Prickett

Despite the city’s rising homicide rate and a recent rash of highly publicized violent crimes, Birmingham-area law enforcement officials say they are optimistic about the city’s long-term crime-fighting prospects, due in part to an array of government agencies working together.

After a violent start to September, which saw seven homicides in its first eight days, Birmingham is on track to have its deadliest year in decades. As of Sept. 20, there have been 86 reported homicides this year, compared to the 79 counted at this point last year, which was the deadliest year for the city since 1994.

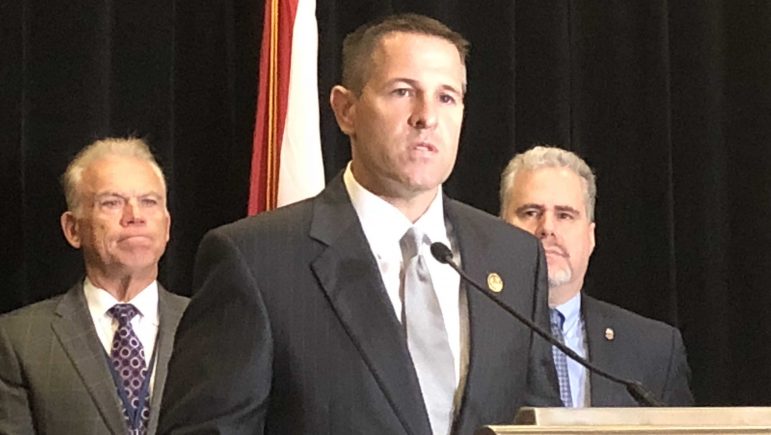

“It’s too high for sure,” said Jay Town, U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Alabama, which is centered in Birmingham. “It makes you wonder if we weren’t putting all of this effort … I shudder to think where those numbers might be.”

Town has been on the job for roughly 13 months — he was one of President Donald Trump’s first U.S. attorney appointees confirmed by the Senate — and he said he has worked to develop a “vertical” model of law enforcement that includes federal, state, county and local departments. It’s a model, he said, that can serve as a crime-fighting method going forward.

“The only promise I can make is that we are establishing long-term processes, and it takes time,” he said. “As much as we would like in the Magic City to have crime disappear overnight, we are taking the painstaking efforts to make sure that there are systems and methods and processes in place that are going to last a lot longer than any of us.”

Town said he sees signs of a potential drop in a preliminary nationwide report from the FBI for the first half of 2017, which showed a .8 percent decrease in violent crime nationwide, compared to the first half of 2016. However that report also showed a .1 percent increase in violent crime for the Southern region of the U.S., including a 3.6 percent hike in the region’s murder rate. The FBI’s full 2017 report is expected to be released in the last week of September.

“Nontraditional Partners”

Town’s optimism also comes from the establishment of two task forces earlier this year. The first of those, the Birmingham Public Safety Task Force, includes a laundry list of law enforcement partners, including metro-area police departments, the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Office, Birmingham City Hall, the Department of Homeland Security, the U.S. Marshals, the FBI, the ATF and state district attorneys — as well as “nontraditional partners” such as the Birmingham Housing Authority and the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles.

The Birmingham Public Safety Task Force has a goal of identifying the “worst offenders” in the Birmingham area, “and then put a case on them that is just, and in a form that carries with it the greatest amount of sanction,” Town said. For instance, if someone the task force identifies as a career criminal is arrested for a crime that has a different punishment on the state level than on the federal level, the task force works to have them prosecuted on the level that can give them the steepest sentence.

But, Town said, “We recognize we can’t incarcerate our way out of this violent crime issue.”

The second task force, the Birmingham Safe Neighborhoods Task Force, takes a preventative approach, partnering with community partners, including philanthropy groups, city departments and after-school organizations, to provide opportunities for youth. It also tries to prevent further criminal behavior by assisting offenders leaving prison.

hat approach has been the public focus for Birmingham Mayor Randall Woodfin — described by Town as someone “who is aggressively pursuing violent crime reduction strategies” — who has dedicated city funding to 24 Birmingham-area youth organizations focused on conflict resolution.

“It’s my judgment that our best option at success is to prevent our next generation from ever, ever getting involved with criminal activity to begin with,” Town said. “We can have all the re-entry programs that we want, we can have all the anti-recidivism programming that we can muster, but I really feel like it is in our best interest to really focus on those youngsters who sit at the corner of abject and temptation. We have to give them a positive alternative.”

“A Constant Balance”

One of the partners on Town’s Birmingham Public Safety Task Force is the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, an organization that approaches crime prevention in a tactile way — by taking illegal guns off the streets.

According to Michael P. Knight, a special agent and public information officer with the ATF, the bureau recently has been more successful in doing that because of help from other law enforcement agencies and their tip lines and Crimestopper programs, as well as the ATF’s own “Report It” mobile app.

“It’s taken a little bit for the agencies to look at and combine their resources, so over the last six months, throughout the state of Alabama — and in particular, the Birmingham area – there’s been a significant seizure of firearms or recovery of firearms, not (just) in one location,” Knight said.

The amount of illegal guns in Birmingham doesn’t directly correlate with the city’s rate of violent crime, Knight said, due to the prevalence of interstate arms trafficking. But taking those firearms off the streets likely prevents more crimes from happening, he said. “Many times, we may recover a firearm that was part of a gun shop theft, but they may not have been used in a crime yet, so we may have thwarted …. crimes,” Knight said.

Community engagement, he said, is a major factor in whether the ATF can be successful in the region. There’s a “trust factor” involved, he said. “We want to go into these communities (and interact with) the public, but we also want to make sure that we are not coming in with such a force that the public doesn’t want us. It’s a constant balance.”

Finding that balance, he said, has been made easier through cooperation with the Birmingham mayor’s office. “We’re not only working with the (Woodfin) administration through their police department, but also through their community engagement department,” he said. “Some of the efforts with community engagement may take a little bit of time because (the administration is) getting established with the community, and we’re getting established with the community.”

“Very Little Foundation”

If violent crime in Birmingham has been on the rise since 2015, as homicide statistics show that it has, why has the progress described by Town and Knight only been happening over the past several months?

Town chalks it up to fresh administrations on both the local and federal level. Town took the job after President Trump took office in 2017; Woodfin took office at the end of that year. Birmingham Police Chief Patrick D. Smith, whom Town describes as an “excellent hire,” took the job in June after a nationwide search.

Previous administrations, he said, did not provide much infrastructure for the incoming leadership. “We didn’t have to start from scratch, but I can tell you, we had very little foundation on which to build,” he said. “But we’ve created it, and we’ve created it quickly. And quite honestly, (Jefferson County) Sheriff (Mike) Hale has been a big part of that, Mayor Woodfin’s been a big part of that, and the cooperation with the feds has been extraordinary.”

That communication is key, Knight said, not only for practical purposes but for shaping the public’s view of law enforcement in the area. “We are talking on a weekly basis, we’re working together on a daily basis so we’re not duplicating efforts,” he said. “Plus, we’re making a difference in impact because now the public can see that there’s a unified front.

“It has been working,” Knight continued. “Just like with any program, there’s resource issues, there’s funding issues, and that’s where we want to make sure that we’re working together to make sure we’re not remiss or not covering something because of a lack of resources.”