In many ways, Rachel Hyche is like any other high school freshman in North Shelby County. She plays piano and likes to sing. She loves her phone.

But the biggest difference is that Rachel is blind. She was born premature.

“I have retinopathy of prematurity, which means that my retinas have been pulled away from my eyes by scar tissue,” Rachel says. “I have light perception, but it’s pretty useless.”

As a result, Rachel learned Braille. It’s the writing system of raised dots that allows blind and visually impaired people to read. It’s also the basis of a competition this weekend in California that Rachel will participate in.

The Braille Challenge is a two-day event in Los Angeles organized by the nonprofit Braille Institute. Students compete in areas such as reading comprehension, speed, accuracy and proofreading. Rachel is one of 10 finalists in her age group.

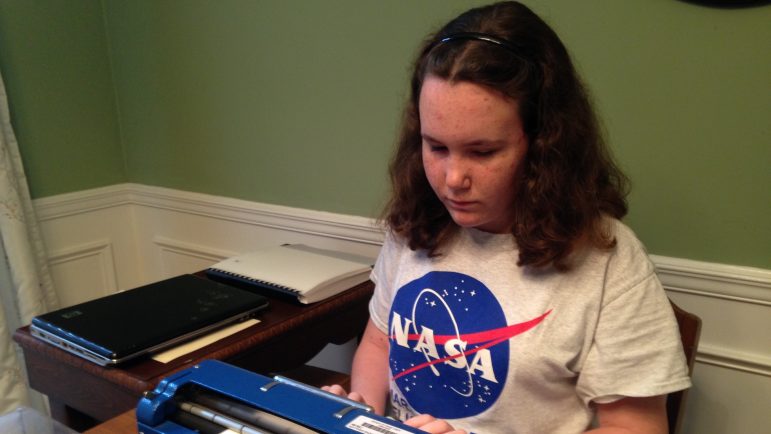

Part of the competition will use a Braille writer. Rachel has hers set up on her family’s dining room table.

It’s looks like a shallow typewriter. It’s blue, with gray buttons, although far fewer than a regular typewriter since Braille is based on a sequence of six dots.

Rachel feeds in the thick paper. The familiar rat-a-tat rings out as Rachel presses the buttons and the machine presses dots into the sheet.

It’s Rachel’s second go around at the Braille Challenge. She was a finalists four years ago.

“I was terrified and I was also really nervous and excited,” says Rachel. “Because if I didn’t win, I would regret it for the rest of my life. I was just scared that the test would be hard and that I wouldn’t win.”

She didn’t place in the top three then, but Rachel says she’s more confident now and she’s had a lot practice with Braille.

“I want to win first place,” says Rachel.

Rachel’s mom, Kim Hyche, is nervous too, but proud. She sees the competition as a way for Rachel to build critical skills for her future.

“For Rachel to have a chance to go to California to participate in this, it’s good for her,” Hyche says. “It’s a good motivator. It pushes you to the next level.”

Braille may have helped blind people for almost 200 years but technology today, particularly text-to-speech, is raising questions of whether Braille is really as necessary. Rachel is an emphatic Braille booster. She says there are downsides to having your phone read everything. Some are aesthetic, such as the irritating computer voice. Others are practical.

“If I’m in a loud area, I can’t hear it very well,” says Rachel. “And then the whole world can hear my speech.”

In other words, there’s no privacy.

In reality, the old and new technology work in tandem. For example, with the Bluetooth device that lets Rachel navigate her iPhone through Braille.

It’s all based on the same set of skills, whether reading off a phone, typing on a Brailler, or winning a Braille competition in Southern California.