Researchers at UAB have found a new way to create stem cells, one they hope will lead to more efficient and personalized medical treatments. The findings were published Tuesday in Cell Reports.

“In humans, we have more than 200 types of cells,” says Kejin Hu, lead researcher and an assistant professor at the UAB Stem Cell Institute. “But [in] all of these 200 types of cells, they contain the same generic material.”

While there are thousands of genes, any individual cell only expresses some of them. The particular combination of genes determines whether the cell is skin or muscle, for instance.

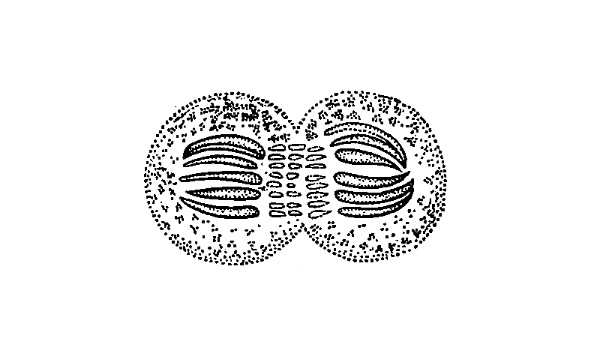

That process of gene expression starts through what’s called transcription. Transcription is kind of the cell’s way of “reading” the genetic information before going on to do something with it. It’s routine and ongoing, but transcription hits pause when the cell divides.

“How does the cell remember which gene is active, which gene is silenced?” says Hu. “How does the transcription machinery go back to the right place?”

Hu says the cell has protein “bookmarks” so it knows where to pick up after it divides. But instead of allowing the cells to continue on their way, researchers can use chemicals to target these bookmarks and remove them. It’s as if the cell’s memory is wiped clean.

Scientists already knew they could target these bookmarks. But what Hu’s research shows is that once they were gone, cells could more easily be “reprogramed” into another type. They become stem cells.

A Simpler Way

This is not the only way to make stem cells, but Hu says this method is a better than current practices.

Embryonic stem cells come from human embryos. As a result, their use in research generates ethical controversy. Scientists can also create stem cells by transplanting the nucleus of an adult cell into an egg cell. But Hu says this method is technically difficult and only a few labs are capable of performing it successfully.

Hu says targeting the transcriptional bookmarks is simpler and could go a long way to developing personal medical therapies from a individual’s own cells. In theory, doctors could grow tissue or organs and heal our bodies like we repair cars. Using the reprogrammed cells from the patient would also eliminate the risk of rejection that comes with embryonic stem cells.

But Hu cautions we’re nowhere near that yet. He says reprogramming human cells is not efficient enough at this point to use clinically. It also takes more time than the nuclear transfer method.

“We still have a long way as a therapy,” says Hu. “We need a lot of improvement.”