There’s only one health department in Alabama where people can go to be tested for tuberculosis. It’s not in the state’s biggest city: Birmingham or any large city. It’s in Perry County, where an outbreak has so far claimed three lives since last year. And it’s getting worse. The infection rate is 100 times higher than doctors say it should be. Now, health officials are trying to get handle on the disease. But it hasn’t been easy.

Lately in Marion, the disease has been spreading fast. Of almost 800 people tested in the last several days, 47 have been positive. People are worried. On a recent night, about 50 residents filed in to the auditorium at the local high school for a town hall meeting put on by health officials.

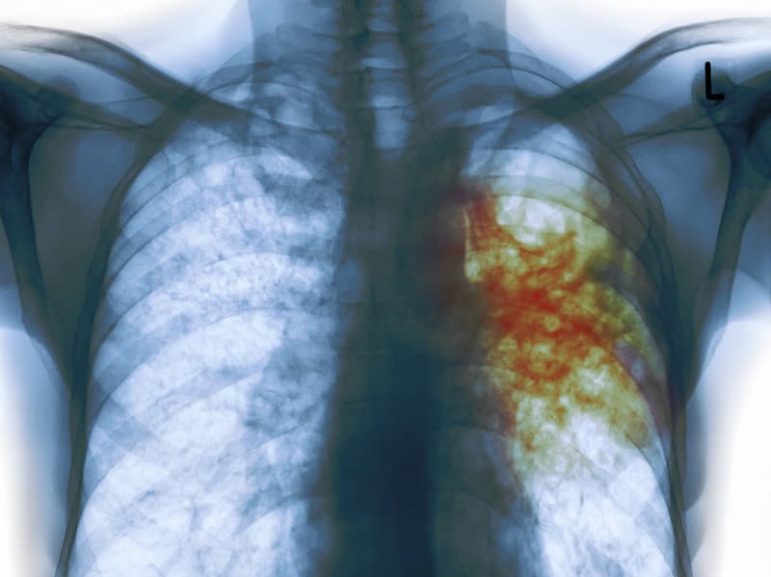

People lined up to grab brochures. TB is airborne, and symptoms include a cough that won’t go away, weight loss, and night sweats. It spreads among people in close contact with one another. People with active TB can transmit it just by coughing or sneezing. Perry County Commissioner Albert Turner urged people to get tested.

“And encourage the people in your church, and encourage the people in your community, while they’re doing this testing,” he said.

A few untreated cases has mushroomed into this much bigger problem. To identify carriers of the disease, the health department last week started paying people to come in to the clinic: $20 for screening, $20 to come back for results, another $20 for a chest x-ray. If they finish treatment, they get an extra $100. In a poor county like this one, it’s a big incentive.

“Uh, it appears to be because it’s working,” Pam Barrett, head of the division of tuberculosis control at the Alabama Department of Health says. “It’s had the health department full every day that we’ve offered the testing.”

It’s a far cry from the days they offered testing at a health fair and people threw bottles at workers. They tried testing without offering money.

“The issue was that we were unable to obtain names of contacts to cases, the cases were not willing to share the names of the people they had been around, so we really didn’t know who to test,” Barrett says.

That’s not uncommon, according to Jeffrey Cirillo, director of the Center for Airborne Pathogens, Research and Imaging at Texas A&M. He says often, health officials quarantine tuberculosis patients. Those infected take a drug for months. That stigma leads people to hide. The good thing about this program, Cirillo says, “is that they’re trying to provide incentives, get people there, so everyone can be treated.”

Since they’ve been offering cash, there’ve been long wait times at the clinic. When he went, Commissioner Turner had to take a number: 176 people were ahead of him.

“Well I signed up, left and came back,” he says.

A few days earlier, resident Vinnie Royster went to get tested. “It was slammed,” she says. “Cars was everywhere, people was everywhere. You couldn’t even get in line. If you got in line everybody in front of you was saying, we just got a number.”

The sight of the crowds made her think, “This is serious.”

“At this point I’m scared. All these people rushing down here. We must be badder than we think,” Royster says.

So she called her primary care doctor and tried to get an appointment there. She could, but she wouldn’t be paid anything for a TB test. That’s ok, she says. Her health is more important than the extra cash.