The recent attack at Ohio State University is the latest to raise a troubling question: how should schools prepare for dangerous intruders? Many districts are moving away from the standard “lockdown” to more active responses that include fighting back, even against gunmen. But some security experts question that guidance.

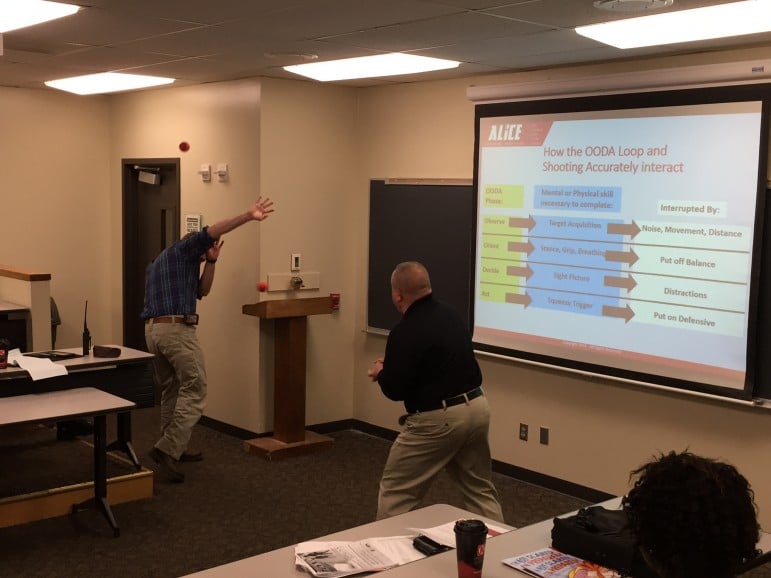

Joe Hendry is not one of them. He’s a safety trainer for a company called the ALICE Training Institute. The retired law-enforcement veteran who served in the Marines is throwing cush balls at a fake-gun-wielding cop in a classroom full of police, educators, hospital staff and business executives at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. It’s all part of an ALICE instructors’ course.

“Watch the physical reaction to stimulus when I throw these balls at his head as fast and as hard as I can,” says Hendry. A few thuds later, he asks, “You see his body do two things?”

The gunman’s arm reflexively came up to protect his head while his body turned away to protect the groin. The point? Even trained officers can’t shoot straight with soft things flying at them.

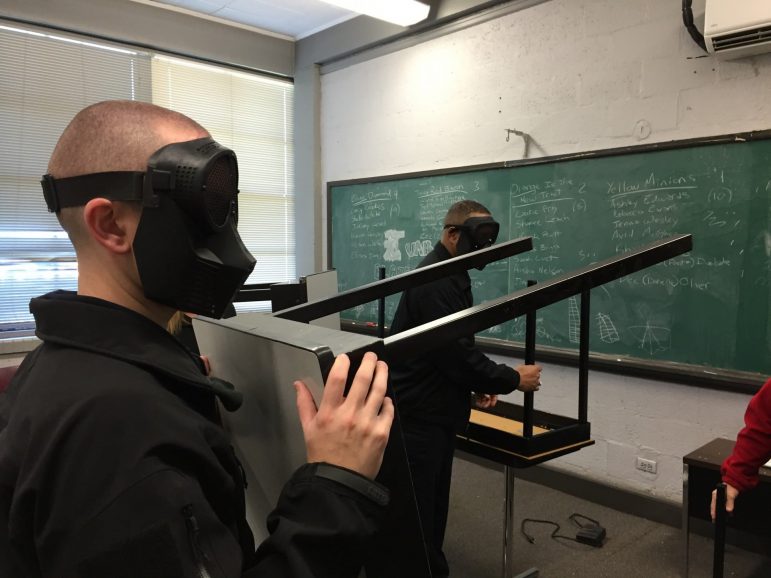

ALICE stands for Alert, Lockdown, Inform, Counter, and Evacuate. The trainees are learning the program so they can go back to their respective institutions and teach their staffs. Hendry takes the group of 20 through lessons on everything from SWAT team response times to breaking windows to swarming techniques.

The next day, the group reconvenes in a vacant building on campus. This long, intense day’s rhythm is briefing, drill, debriefing. The drills include “standard lockdown,” barricading, evacuating, and countering. After a drill where the gunman breached a furniture barricade, an officer who didn’t get her mask on fast enough was hit with training pellets and had to go to the emergency room with bloody facial wounds.

Hendry says this type of training is needed partly because old-school lockdowns – shut the doors, turn off the lights and hide – are restrictive, and inappropriate when attackers are in the building.

“That single-option response being taught is not actually [for] an active shooter event,” he says. “It was meant for drive-by shootings.”

ALICE teaches potential targets that they have choices, including the controversial last resort of “countering.” That could mean distraction, throwing books, or group tackling. There’s no national database showing how many schools prepare this way, but critics and supporters agree the number is increasing. Hendry says 3,700 K-12 districts have had ALICE training. That’s about a quarter of the country.

“We should be able to change our response based on our circumstance and not be locked into anything. I think pretty much the nation is switching over right now, because they’ve seen the failure of things that happened at Columbine and Virginia Tech and Aurora, Colorado,” he says. The drills at UAB seem to support the ALICE approach: There were far more pellet-stung casualties when victims locked down than when they had options like evacuating, barricading, or countering.

Hewitt-Trussville High School resource officer Chuck Bradford says he plans to bring ALICE techniques back to his fellow officers and to local businesses whose leaders have asked for it.

“What we have to do is kind of re-educate our educators, our administrators, even our police officers, to kind of show them this new movement of better training, better opportunities for survival.”

There has been an evolution in thinking: Federal agencies now recommend a “Run, Hide, Fight” protocol (see pages 63-66), with the “Fight” component meant only for adults.

But not everyone is on board. School security consultant Ken Trump is a critic of ALICE and Run Hide Fight. He says after the tragedy of Sandy Hook, people needed to “feel empowered,” but adds, “there’s a difference between feeling more safe, versus actually having a false sense of security that could teach you just enough to get yourself killed.”

And Trump is most worried about that with kids:

“Some people are advocating to teach children what our law enforcement officers train their entire career to do, putting that pressure and decision upon them to make split-second life-and-death decision, based on an hour or two of training they’ve only received one time.”

Of course, ALICE staff want students and adults to get their training more than once. They say their programs are age-appropriate, and that, worst of all, conditioning potential victims to hold still makes them easy targets.

Regardless, decisions on emergency preparation are made at state and local levels, so training to fight back against gunmen could be coming to a school near you.

For a previous NPR report on ALICE training, click here.