Civil Rights, Voter ID laws, Felon Rights. These topics aren’t foreign for teachers and students in Southern classrooms. But what happens when pressure to teach to the test prevents challenging conversations? In the Southern Education Desk’s final piece on Teaching Touch Topics, WWNO’s Mallory Falk looks at one program in New Orleans that’s trying to move beyond rote memorization and make room for controversy.

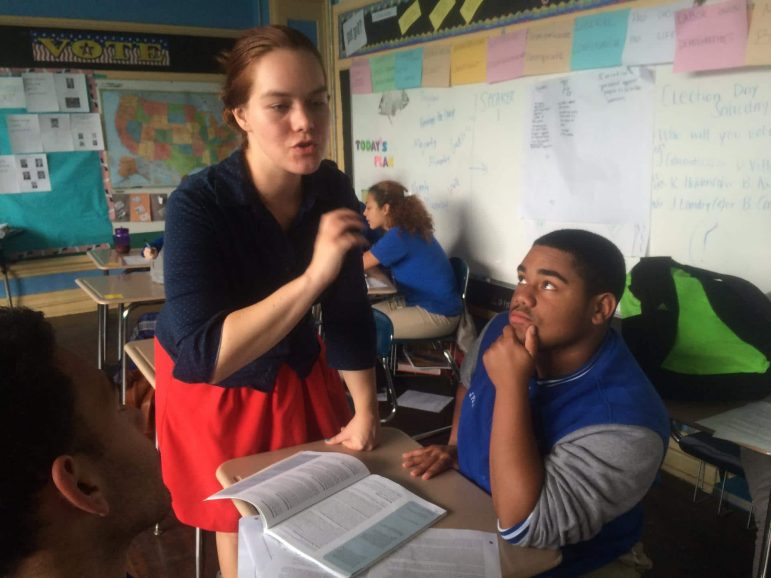

In a class at the end of the day at New Orleans Charter Science and Math High School, a fierce debate unfolded in Sarah Cannon’s Civics class. The question on the floor — should felons lose the right to vote?

The 11th and 12th grade students made their cases with primary texts. Like a legal report from conservative think tank The Heritage Foundation and a speech from former attorney general Eric Holder.

“People who kill people don’t always stay in jail for a lifetime. And those people, they don’t need to vote. Period. They broke the law and now they have to take their lick for it. It’s the consequences,” one student said.

Still another student said, “According to Eric Holder, throughout America 2.2 million black citizens or nearly 1 in 13 African American adults are banned from voting because of these laws.”

The debate was part of a semester-long unit on the Voting Rights Act – developed in partnership with the Southern History Project. That’s a non-profit that designs Southern history curricula.

Sheila Sundar is the project’s director. Working as a high school teacher and coach, she noticed a disturbing trend — many students were missing basic knowledge or had their facts mixed up.

Sundar recalls an 11th grade history class, where a student made a reference to the abolitionist Martin Luther King, who was actually a civil rights leader.

There was another class, she says, where only a quarter of the students knew about Jim Crow laws.

Sundar says teachers had to chose between filling in gaps “and engaging in the big moral and civic and geographic questions that are relevant to our communities today.” She formed the Southern History Project to help them do both. She launched a pilot program at a local charter school last year…but hit a major stumbling block.

“The immediate challenge of preparing students for a test governed the social studies curriculum,” she says.

There’s a lot riding on the US history end-of-course exam. It factors into a school’s letter grade. And that determines whether or not a school stays open. So there’s immense pressure to just quickly drill in facts.

“Each time period gets a few days of coverage,” she says.”And if we give every piece of content two days because we have to move on, move on, move on, that opportunity to linger and ask big questions is compromised.”

Sundar says teachers aren’t afraid of tough conversations…they simply don’t have time.

“Our teachers are cutting the conversation just at that moment when it can make the content stickier and the lessons of history most enduring,” she says.

Students might be able regurgitate facts – and pass tests – in the short run. But in the long run, they lose out,” she says.

“The gains of preparing for a test are immediate. And the gains of good education are amorphous. We’re on the crux in the south of asking enormously critical questions about who belongs and who doesn’t, who should have rights and who doesn’t,” Sundar says. “And if we don’t teach well, our kids can’t answer those questions. They can’t advocate for the change that they want to see.”

She found a new partner school and plans to expand across New Orleans and the South, so more classes can engage in debates like the one in Sarah Cannon’s civics class. A debate so engaging, students protest and groan when they learn class is almost over.

Eleventh grader Morgan Glover says Cannon’s class feels different.

“In a normal History class, you know, you have the big huge thick textbook and you’re sitting down and it’s just lecture lecture lecture and it’s very boring,” Glover says. But in this class we get to go back and forth. Flashing back to when they created the constitutions and amendments, and then we get to flash forward in time and know what goes on in our world today.”

This report is supported by a grant from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.