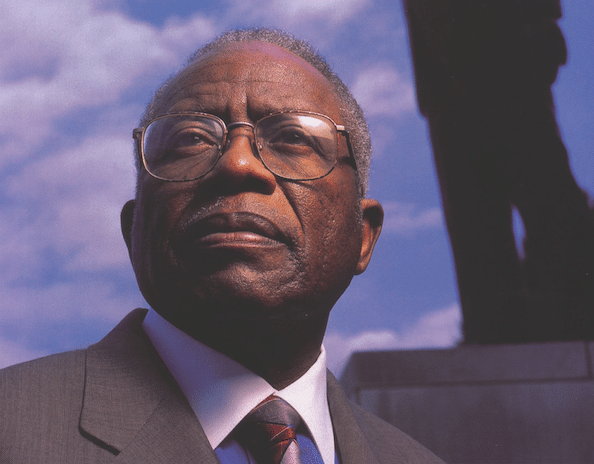

This month marks the 50th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the law that abolished literacy tests and other tools designed to keep black people from voting. Part of the foundation for that law was laid by civil rights attorney Fred Gray. To honor this occasion, WBHM is airing a series of conversations with Gray. This is part two. Listen to part one, where Gray discusses the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

In 1957, on the heels of his successful lawsuit that ended the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Fred Gray represented a group of African American voters from Tuskegee who were shut out of voting in local elections when the Alabama Legislature re-drew the city limits in such a way as to remove them from the city. Gray sued the State in Federal Court. Almost four years later, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that race-based gerrymandering was unconstitutional.

While the winds of change were blowing through the courts, the State of Alabama refused to quietly acquiesce to de-segregation. In 1963, nine years after the Supreme Court declared segregated schools unconstitutional, not a single public school in Alabama was integrated.

In January of 1963, George Wallace became Governor. Fred Gray recalls his inaugural address.

“When I saw him saying segregation today, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever, I felt that was the beginning, I was going to try to help keep him busy.”

That same month Gray filed a de-segregation lawsuit against the Macon County Board of Education, and Judge Frank Johnson ordered Macon County to integrate the schools when they opened in the fall. Instead of allowing local whites to comply with the court order, the Governor intervened.

“But for some reason George Wallace decided to send the state troopers over here, prohibited and would not let them de-segregate the schools,” Gray said. “So I concluded that if he could do that I could add him as a party and the state board of education as a party, add the state superintendent as a party and ask the court to desegregate all of the school systems in Alabama which had not been under court order and desegregate everything that had been under the control of the state board of education.”

Gray sued Wallace along with the state school board and the following year the Federal courts ordered the integration of all Alabama public schools. Gray sued Wallace again over the Selma to Montgomery march.

“They called me after Bloody Sunday that evening and asked me to come over to see John Lewis and I had another contact with him and time won’t permit to go into all that. But I represented him. And before the close of day the next day I filed a case, Williams vs. Wallace.” Gray said, “It is that case that laid the foundation and made it so that could march from Selma to Montgomery and ultimately the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.”

Judge Frank Johnson not only granted the Selma marchers the right to finish their march, but he also compelled the State of Alabama to provide police protection for the participants.

In 1972, Gray represented the survivors of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, a group of African American men who were followed by the Federal Government to observe the effects of on men when the disease is untreated. The resulting class action against the United States led to compensation for the survivors and, ultimately, an apology from President Bill Clinton.

When Gray was preparing his autobiography, he spoke with the then elderly George Wallace who apologized for his racist past. Gray believes his conversion was sincere.

At 84-years-old, Fred Gray still practices law in Tuskegee. He says 4 things need to happen before we can finally destroy segregation.

“One, while we’ve made a tremendous amount of progress that racism in this country is still a major problem. Secondly, it’s not going to go away by itself. The Montgomery Bus Boycott didn’t start by itself, the Selma to Montgomery March didn’t start by itself. So, you’re going to have to come up with a plan to do away with racism. And once you get a plan, a plan is no good unless the third thing is you have to implement it. And everybody wants all these problems to be solved but they want somebody else to solve them. It’s going to take everybody working together to solve them. It’s going to have to start at the top with a loud voice saying racism is wrong, we’re going to eradicate it. Then they’re going to have to come up with a plan. Then we can solve the problem.”