The number of Latinos in America’s schools is rising faster than any other group’s. And their share of the school population is rising fastest in the South. Many don’t speak English as their first language, making them “language-minorities.” And the question of how best to educate them is becoming crucial in places with relatively little practice or bilingual history – places like Alabama, Georgia, and Tennessee. So WBHM is kicking off a four-part series on language-minority education in the South. In Part One, we cross the border (into Georgia) to see an innovative school and a counterintuitive concept in action. Read below, or listen above.

Unidos Dual Language Charter School in Clayton County, Georgia is in the flight path of Atlanta’s airport. It looks like a growing number of America’s public schools: it’s a little run-down, and its students are brown – a little more than half African-American, just less than half Latino. Ninety percent are on free or reduced lunch.

But what’s happening inside its Pre-K through eighth-grade classes is anything but typical of the U.S. or the South. Basically, Spanish-speaking Latino kids are getting much of their instruction in the language they know, and African-American kids from the neighborhood are picking up a second language.

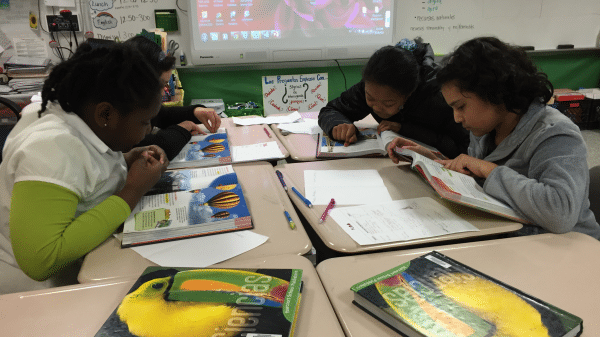

That’s accomplished through a ratio of Spanish-to-English instruction that changes depending on the grade level. For example, Unidos kindergarteners get 70 percent Spanish and 30 percent English, in the form of one block of English Language Arts so they can learn to read and write in English. Their specials (gym, art) are in English, too. So their math, their other language arts lessons, their science, and their social studies are taught in Spanish. Practically speaking, that means kindergarteners stay with one Spanish-speaking teacher most of the day. By second grade, though, the ratio at Unidos is 50-50, and teachers have to do a lot more “trading off” – students, subjects, and languages. These arrangements are one of the reasons experts say a high degree of collaboration is key to making a dual-language school work.

Speaking of which, in the first class I see, native Columbian John Rendon is teaching math in Spanish to a roomful of Latino and African-American second-graders. The kids are enthused, almost all of them raising their hands, eager to show their teacher what they know. Maybe even more tellingly, he makes a joke that pretty much all the kids get.

I speak one-on-one with a half-dozen African-American kids, some whom admittedly were “volunteered” for me, but others I randomly stop in the hall. With the degree of variability you’d expect from the second- through fifth-graders who spoke with me, they could all converse in Spanish. And their accents are solid, too.

One of them, fourth-grader Gabriela Washington, is amused by my less-than-polished cadence. I ask her in Spanish how she’s doing, and she gives me a polite, you-mean-well chuckle. Later I ask why math is her favorite subject. She responds in Spanish, “because it’s very easy.”

In a mainly monolingual country where so many poor black students face low expectations and educational opportunity gaps, this degree of fluency surprises people.

“To see an African-American child walk up to you and speaking fluent Spanish, it takes them off for a minute, but then they smile,” says Tony McCreary, Unidos parent, PTA president, and volunteer cafeteria monitor. I ask if he gets questions or quizzical looks when he tells people that his children are not just learning Spanish, but learning their math, their science, their social studies in Spanish.

“Yeah, quite often. But then I also let them know that with my wife being Hispanic, my kids are blackish, so this is what they need to learn.”

But the former college recruiter is even more enthusiastic about potential benefits he sees for all Unidos students.

“I understand that if there’s something different you can add on to your resume, then you say, ‘Okay, this kid attended a dual language school? Yeah, that’s somebody we really want to look at and bring into our institution.’”

And a growing body of research shows benefits not just for English-speakers. Though it’s a counterintuitive concept, it turns out that if you teach language-minorities core subjects in their native language, they do better in school, including learning English. In other words, teaching, say, Latino students math in Spanish often leads to better overall performance and better English compared to kids in English immersion programs.

Unidos academic coach and parent Jeannie Myers has seen the drawbacks of spending so much critical time on language, not content.

“If we immerse our students so that they can manage that language before going into content, they fall further behind,” she says. But, “Students who learn in the language may start off with some lag [in speaking English], but eventually they catch up and they do really well, versus having two or three years of nothing – only language.”

The reasons kids can eventually have better English after being taught core subjects in Spanish are complex; they have to do with brain development, having knowledge and concepts to attach words to, and with getting language-minorities to buy in. Myers, who’s originally from the Dominican Republic, says that motivational aspect includes parent involvement – a less intimidating endeavor when one’s language is spoken throughout the school building.

“It’s a lot easier for those parents to say, ‘Can I help you with something? I can do your bulletin board in Spanish, because I can’t do it in English.’”

The way “dual-language” schools (the rough synonym “bilingual” has become a loaded word and is used less frequently) operate varies, but basically, students learn literacy and content in two languages with at least half their instruction in the non-dominant tongue. In the U.S. that’s usually Spanish, though there are more and more programs using other languages.

Regardless, the approach seems to be working for shy fifth-grader and aspiring science teacher Melissa Padron. She says the English and the language-hopping she’s learning at Unidos helps her family.

“My dad works at this company,” she says. “Sometimes, he gets emails or letters, and he asks me, ‘What does it say?’ I help my dad and my mom. I technically feel like a mini-teacher.”

That could be good practice for Melissa, and as we’ll see later in the series, it could be good for the future pool of bilingual teachers and for the economy as a whole.

Melissa’s school’s test scores are decent – roughly average for the demographics. But Unidos kids are becoming bilingual, so dual-language education is apparently not a zero-sum game (even when a large portions of the students’ instruction is in a language that’s not on the test). And of course, there are things that standardized tests can’t measure. Gabriela Washington tells me bilingual people get better-paying jobs, and that one of her dreams is to travel with an Unidos classmate.

“My best friend is from Panama, and she says it’s a really nice place.”

Maybe all the noise from one of the world’s busiest airports isn’t just a nuisance.

That was Part One of our four-part series on language-minority education in the South. Click here for Part Two and take a trip to a different school where kids are learning English, Spanish, Mandarin, and more. Support for this series comes from The Equity Reporting Project: Restoring the Promise of Education, which was developed by Renaissance Journalism with funding from the Ford Foundation.